|

|

Rudyard Kipling’s famous poem “The White Man’s Burden” was published in 1899, during a high tide of British and American rhetoric about bringing the blessings of “civilization and progress” to barbaric non-Western, non-Christian, non-white peoples. In Kipling’s often-quoted phrase, this noble mission required willingness to engage in “savage wars of peace.”

Three savage turn-of-the-century conflicts defined the milieu in which such rhetoric flourished: the Anglo-Boer War of 1899–1902 in South Africa; the U.S. conquest and occupation of the Philippines initiated in 1899; and the anti-foreign Boxer Uprising in China that provoked intervention by eight foreign nations in 1900.

The imperialist rhetoric of “civilization” versus “barbarism” that took root during these years was reinforced in both the United States and England by a small flood of political cartoons—commonly executed in full color and with meticulous attention to detail. Most viewers will probably agree that there is nothing really comparable in the contemporary world of political cartooning to the drafting skill and flamboyance of these single-panel graphics, which appeared in such popular periodicals as Puck and Judge.

This early outburst of what we refer to today as clash-of-civilizations thinking did not go unchallenged, however. The turn of the century also witnessed emergence of articulate anti-imperialist voices worldwide—and this movement had its own powerful wing of incisive graphic artists. In often searing graphics, they challenged the complacent propagandists for Western expansion by addressing (and illustrating) a devastating question about the savage wars of peace. Who, they asked, was the real barbarian?

|

|

| |

INTRODUCTION

The march of “civilization” against “barbarism” is a late-19th-century construct that cast imperialist wars as moral crusades. Driven by competition with each other and economic pressures at home, the world’s major powers ventured to ever-distant lands to spread their religion, culture, power, and sources of profits. This unit examines cartoons from the turn-of-the-century visual record that reference civilization and its nemesis—barbarism. In the United States Puck, Judge, and the first version of a pictorial magazine titled Life; in France L’Assiette au Beurre; and in Germany the acerbic Simplicissimus published masterful illustrations that ranged in opinion and style from partisan to thoughtful to gruesome.

In the “civilization” narrative, barbarians were commonly identified as the non-Western, non-white, non-Christian natives of the less-developed nations of the world. Three overlapping turn-of-the-century conflicts in particular stirred the righteous rhetoric of the white imperialists. One was the second Boer War of 1899–1902 that pitted British forces against Dutch-speaking settlers in South Africa and their black supporters. The second was the U.S. conquest and occupation of the Philippines that began in 1899. And the third was the anti-foreign Boxer Uprising in China in 1899–1901, which led to military intervention by no less than eight foreign nations including not only Tsarist Russia and the Western powers, but also Japan.

Civilization and barbarism were vividly portrayed in the visual record. The word "Civilization" (with a capital “C”), alongside “Progress,” was counterposed against the words “barbarism,” “barbarians,” and “barbarity,” with accompanying visual stereotypes. Colossal goddess figures and other national symbols were overwritten with the message on their clothing and the flags they carried.

The archetypal dominance of “Civilization” over “Barbarism” is conveyed in a 1902 Puck graphic with the sweeping white figure of Britannia leading British soldiers and colonists in the Boer War. A band of tribal defenders, whose leader rides a white charger and wields the flag of “Barbarism,” fades in the face of Civilization’s advance. The caption, “From the Cape to Cairo. Though the Process Be Costly, The Road of Progress Must Be Cut,” states that progress must be pursued despite suffering on both sides. The message suggests that the indigenous man will be brought out of ignorance through the inescapable march of progress in the form of Western civilization.

|

|

|

|

“From the Cape to Cairo.

Though the Process Be Costly, The Road of Progress Must Be Cut”

Puck, December 10, 1902

Artist: Udo Keppler

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[cb01-026_puck_1902_Dec10_CapeToCairo_loc]

In this 1902 cartoon, Britain’s Boer War and goals on the African continent are identified with the march of civilization and progress against barbarism. Brandishing the flag of “Civilization,” Britannia leads white troops and settlers against native forces under the banner of “Barbarism.”

|

|

| |

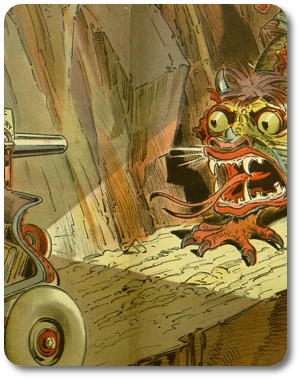

Other graphic techniques were used by cartoonists to communicate this message. For example, the light of civilization literally illuminated vicious, helpless, or clueless barbarians. In “The Pigtail Has Got to Go,” a white-robed goddess wears a star that radiates over a Chinese mandarin. A more earthly approach is taken in the graphic “Some One Must Back Up” that heads this essay. Here the “Auto-Truck of Civilization and Trade” shines a headlight upon a raging dragon and sword-wielding Chinese Boxer whose banner reads “400 Million Barbarians.” In the imagery of the civilizing mission, China is portrayed as both backward and savage. The aggressive quest for new markets—China’s millions being the most coveted—was justified as part of the benevolent and inevitable spread of progress.

|

|

| |

| |

| |

[cb27-004_1900_Judge_BackUp_000016]

[cb30-021_puck_1898_Oct19_cover_1290728_y]

Pro-imperialist cartoons often depicted the West as literally shining the light of civilization and progress on barbaric peoples. In these details, the headlight of a modern vehicle (Judge, 1900) and starlight from a goddess of “civilization” (Puck, 1898) illuminate demeaning caricatures of China.

|

|

| |

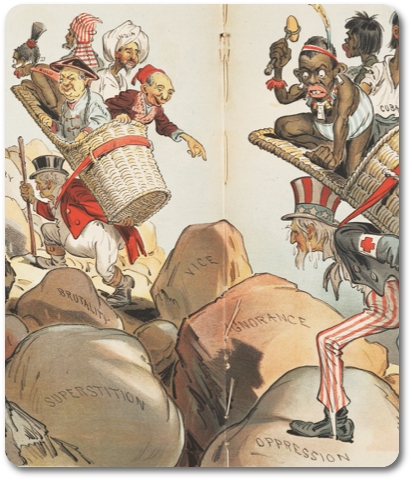

Long-standing personifications and visual symbols for countries were used by cartoonists to dramatize events to suit their message. Anthropomorphizing nations and concepts meant that in an 1899 cartoon captioned “The White Man’s Burden,” the U.S., as Uncle Sam, could be shown trudging after Britain’s John Bull, his Anglo-Saxon partner, carrying non-white nations—depicted in grotesque racist caricatures—uphill from the depths of barbarism to the heights of civilization.

|

|

| |

“The White Man’s Burden (Apologies to Rudyard Kipling)” (detail)

Judge, April 1, 1899

Artist: Victor Gillam

Source: The Ohio State University

Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum

[view]

[cb25-141_1899_Judge_10386_osu]

Britain’s John Bull leads Uncle Sam uphill as the two imperialists take up the “White Man’s Burden” in this detail from an overtly racist 1899 cartoon referencing Kipling’s poem. |

|

|

| |

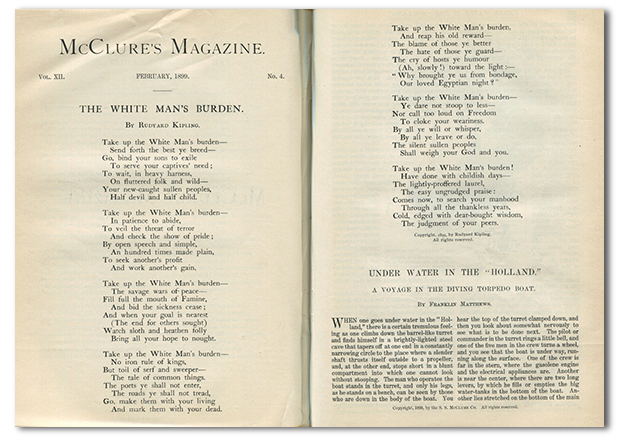

The cartoon takes its title from Rudyard Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden.” Published in February, 1899 in response to the annexation of the Philippines by the United States, the poem quickly became a famous endorsement of the civilizing mission—a battle cry, full of heroic stoicism and self-sacrifice, offering moral justification for U.S. perseverance in its first major and unexpectedly prolonged overseas war.

|

|

|

| |

Original publication of Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “The White Man’s Burden.”

McClure’s Magazine, February, 1899 (Vol. XII, No. 4)

[cb02-027_28_Mcclures]

|

|

| |

Newly conquered populations, described in the opening stanza as “your new-caught, sullen peoples, half-devil and half-child” would need sustained commitments “to serve your captives‘ needs.”

Take up the White Man's burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need;

To wait in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half-devil and half-child.

Expansionism promulgated under the banner of civilization could not escape being carried out in global military campaigns, referred to as the “savage wars of peace” in the third stanza:

Take up the White Man's burden—

The savage wars of peace—

Fill full the mouth of Famine

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

The end for others sought,

Watch sloth and heathen Folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.

Such avowed paternalism towards other cultures recast the invasion of their lands as altruistic service to humankind. The aggressors brought progress in the form of modern technology, communications, and Western dress and culture. Christian missionaries often led the way, followed by politicians, troops, and—bringing up the rear—businessmen. Education in the ways of the West completed the political and commercial occupation. Cartoons endorsing imperialist expansion depicted a beneficent West as father, teacher, even Santa Claus—bearing the gifts of progress to benefit poor, backward, and childlike nations destined to become profitable new markets.

In the United States, the Boer War, conquest of the Philippines, and Boxer Uprising prompted large, detailed, sophisticated, full-color cartoons in Puck and Judge. Although these magazines were affiliated with different political parties—the Democratic Party and Republican Party respectively—both generally supported pro-expansionist policies. Opposing viewpoints usually found expression in simpler but no less powerful black-and-white graphics in other publications. Periodicals like Life in the U.S. (predecessor to the later famous weekly of the same title), as well as French and German publications, printed both poignant and outraged visual arguments against the imperialist tide, often with acute sensitivity to its racist underpinnings.

These more critical graphics did not exist in a vacuum. On the contrary, they reflected intense debates about “civilization,” “progress,” and “the white man’s burden” that took place on both sides of the Atlantic. It was the anti-imperialist cartoonists, however, who most starkly posed the question: who is the real barbarian?

|

|

| |

|

|

|