| |

|

|

| |

OCCUPATION & AFTERMATH

Wars for Civilization

The Hague Convention of 1899, signed by the United States, Britain, Russia, France, China, Persia, and Germany, was the first international treaty establishing laws of civilized warfare, but its provisions were completely ignored during the Boxer expedition. Looting, summary executions, destruction of civilian housing, and violent reprisals spread from Beijing into the countryside. Foreign troops determined to punish the Boxers ravaged the region relentlessly.

Of course, the Hague conventions also failed to protect Western populations from each other. The use of indiscriminate violence against a civilian population in 1900, like the scorched earth tactics used against Boers and Filipinos, anticipated the savagery of the total war the Western powers would inflict on each other in World War l.

But the popular imagery contained deep contradictions inherent in the character of highly unequal imperial wars. The foreign armies, with vastly superior military technology, found themselves embedded in a huge civilian population where it was difficult to distinguish the innocent and the guilty. They had to justify their actions to the public at home as an act of a civilizing mission designed to rescue the Chinese people from backwardness, yet they endorsed vicious revenge against the unknown Boxer hordes. At the same time, popular media tried to spare the home population from a realistic picture of military confusion and brutality, and often depicted warfare as an innocent game, similar to outdoor sports and hunting, but hardly involving death and destruction. The positive pictures included both humorous individual portraits and jokes alongside impressive photographs of disciplined military formations, to show that war was a normal occupation under rational control by seasoned commanders.

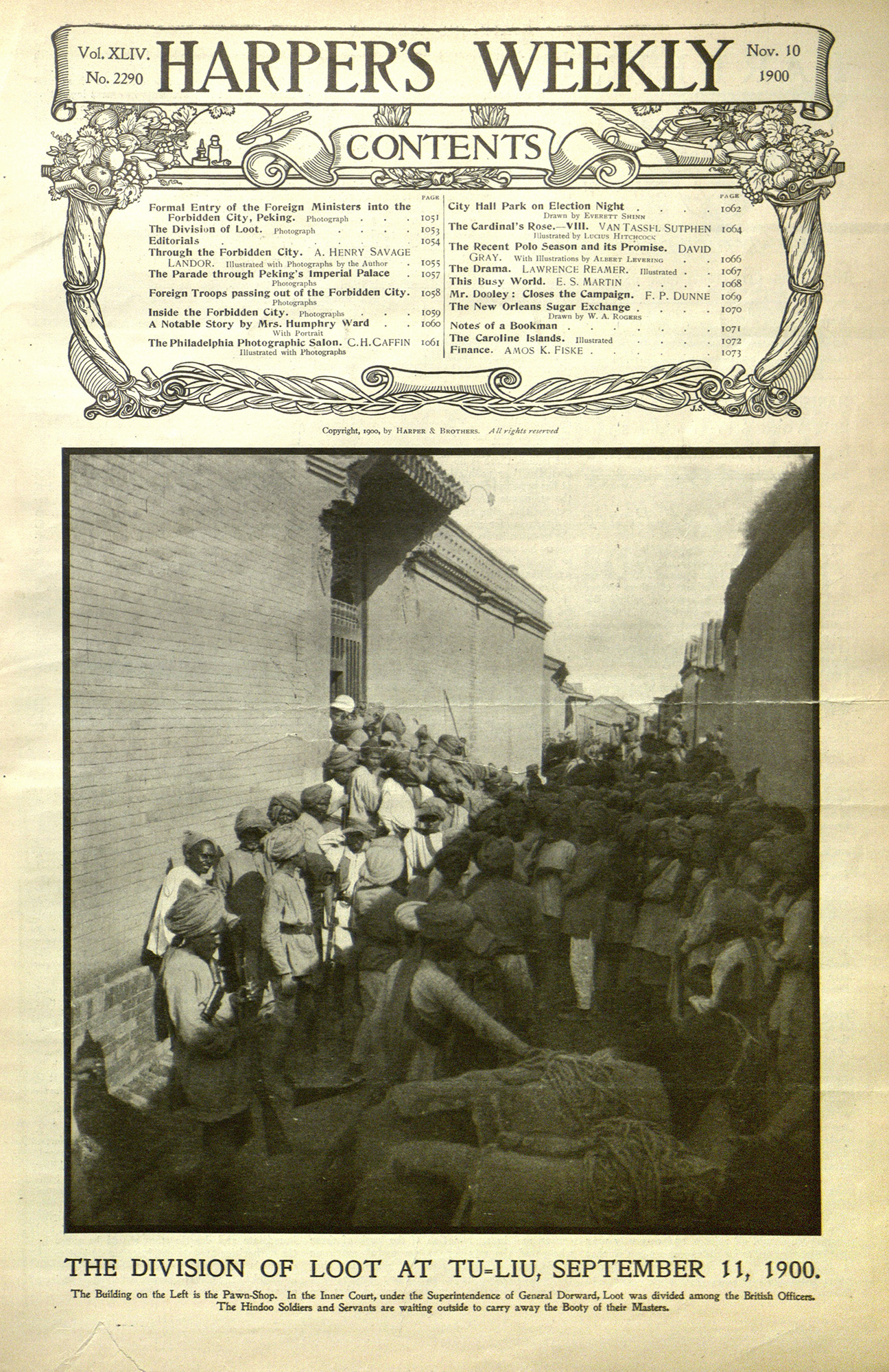

On the other hand, the vigorous debate over looting, in which each of the foreign countries accused the other of the worst offenses, revealed a small segment of the destruction inflicted on the Chinese population. Clearly, all forces plundered the cities that they occupied, taking items ranging from precious artifacts in the Imperial collection to the ordinary possessions of civilians. Open markets sold loot to foreign and Chinese buyers. The captured relics, often labeled as “imperial treasures,” have turned up in regimental mess halls, local museums, art galleries, and private dealers throughout the Western world and Japan.

While committing atrocities, looting the capital, and denouncing the majority of Chinese as Oriental hordes, Western governments and publics still had to maintain that there was a civilized element in Chinese society with whom they could negotiate and do business. Only then could they remove their troops and promote peaceful commercial relations with the country.

Li Hongzhang & Wu Tingfang Praised as Chinese Peacemakers

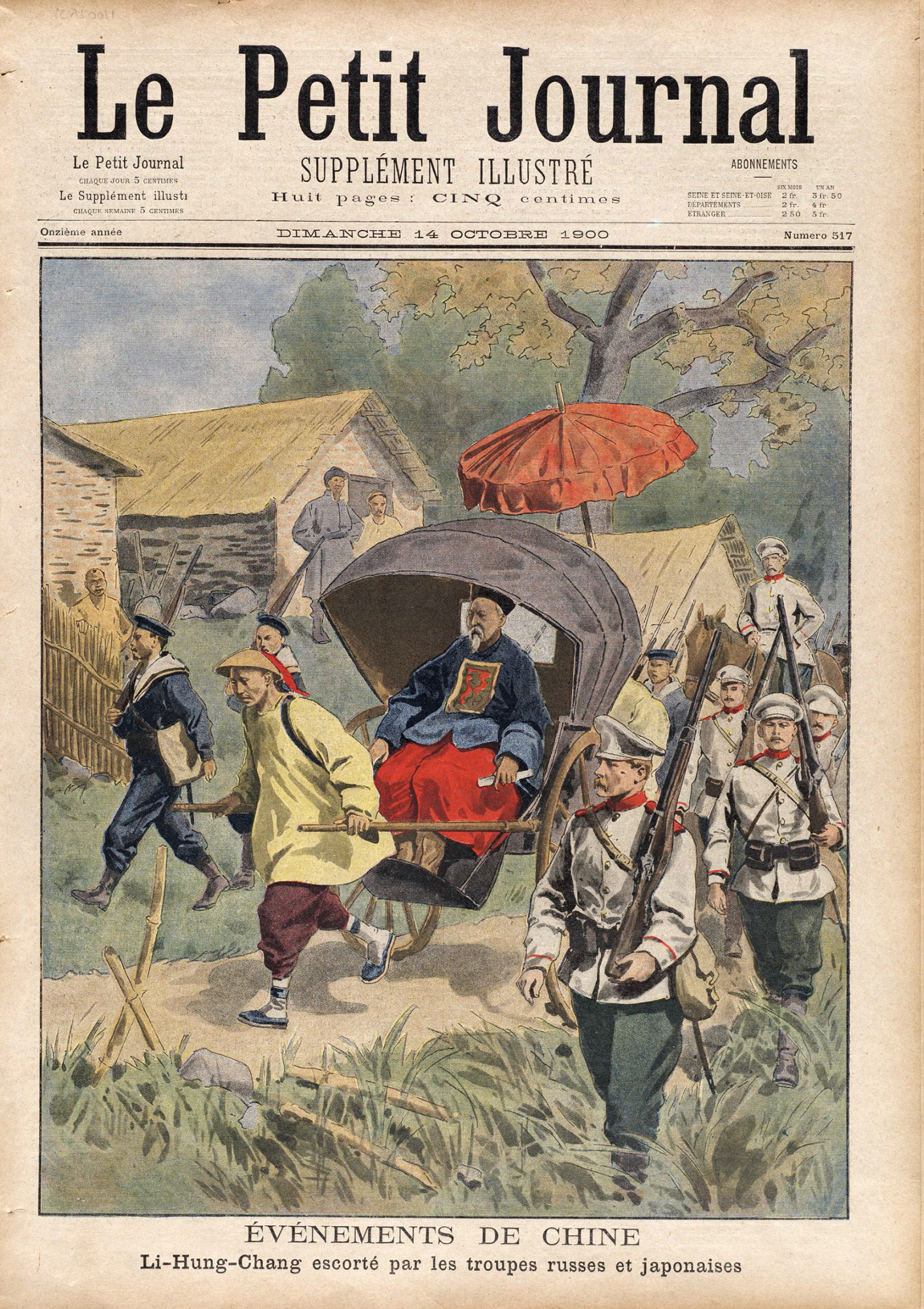

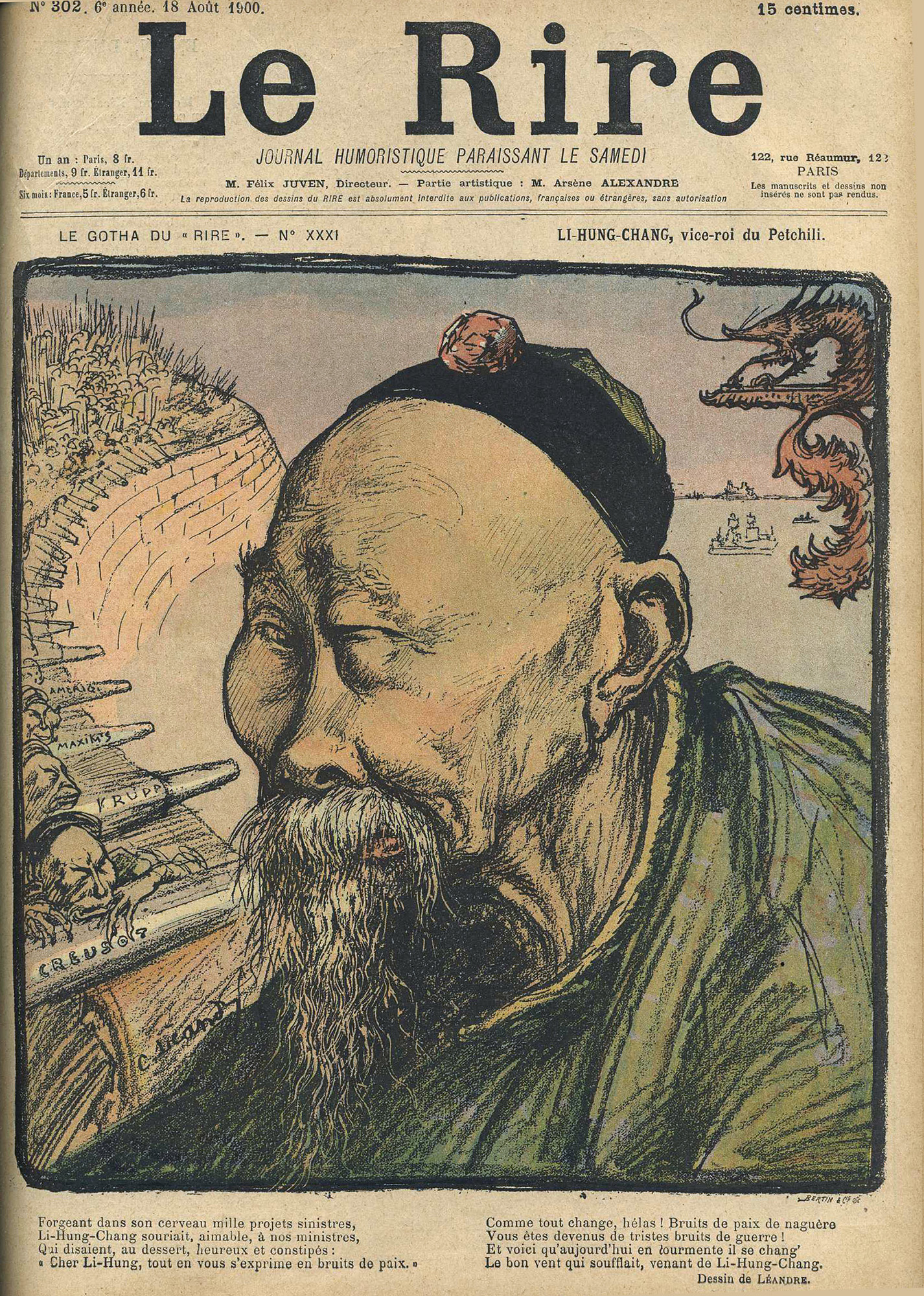

In the midst of racist fears and rampant looting, certain Chinese officials garnered praise from Western diplomats. Li Hongzhang (1823-1901) had led Chinese troops to resist Japan in the Sino-Japanese War, but he also negotiated the treaty settlement that ended the war. In 1896 he traveled to Europe to attend the coronation of Emperor Nicholas ll of Russia. After he toured Britain in the same year, Queen Victoria made him a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian order. Reluctantly, he had to support the court's decision for war, but in 1901 Li negotiated the protocol ending the Boxer intervention, earning compliments from foreigners for bringing peace, but denunciations from Chinese for accepting the payment of huge indemnities. He died two months later, and received the title of Marquis from the Guangxu emperor. Li was the only Chinese person to gain titles of nobility from both foreign and Chinese governments.

|

|

|

| |

Caption: “Li-Hung Chang Escorté par les Troupes Russes et Japonaises”

Le Petit Journal, Supplément Illustré, October 14, 1900

Source: Widener Library, Harvard University

[lpj_1900_10_14_widener]

|

|

|

| |

“Forgeant dans son cerveau mille projets sinistre,

Li-Hung-Chang souriait, aimable, a nos ministres,

Qui disaient, au dessert, heureux et constipes:

‘Cher Li-Hung, tout en vous s’exprime en bruits de paix.’

Comme tout change, helas? Bruits de paix de naguere

Vous etes devenus de tristes bruits de guerre!

Et voici qu’aujourd’hui en dourmente il se chang’

Le bon vent qui soufflait, venant de Li-Hung-Shang.”

Translation: “Forging in his brain one-thousand sinister projects,

Li Hongzhang smiled kindly at our ministers,

Who said, at dessert time, sated and constipated,

’Dear Li Hong, you have always spoken with the voice of peace.’

How things change, Alas! The voice of peace of times gone by

has become the sad voice of war!

Just see how his gentle breath, in torment, has changed.”

Le Rire, August 18, 1900

Artist: Charles Léandre

[dh7067_e1380_fr_Hogge]

|

|

|

| |

“Li Hung Chang, China’s Greatest Viceroy and Diplomat

(photographed in his Yamen, Tientsin, China, Sept. 27, 1900).”

Stereograph, 1901

[libc_1901_3c10736u]

|

|

| |

One other notable cosmopolitan Chinese official deeply impressed the foreign audiences. Wu Tingfang (1842-1922) served as minister to the U.S., Spain, and Peru, and ably defended the Qing government position. Born in the Straits Settlements, the British colony in Malaya, he studied in Hong Kong, learning fluent English. He studied law in London, becoming the first Chinese barrister to practice law when he returned to Hong Kong. As an unofficial member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong, he promoted the rights of the Chinese population, but hostility from British colonialists forced him to leave the colony for Beijing. He joined Li Hongzhang’s service and traveled widely, lecturing to Western audiences about the glories of Chinese civilization, the injustices inflicted on Chinese immigrants, and the need to support the reform party in the Qing court. At New York dinner parties, attended by the business and cultural elite, Wu became a popular after-dinner speaker.

|

|

|

| |

“One of the Season’s Most Popular After-Dinner Speakers.

Chinese minister Wu Ting-Fang addressing a

gathering of New York merchants”

Harper’s Weekly, 1900

[harpers1900_01_030]

|

|

| |

Penetrating the Forbidden City

Under the terms of the treaty, foreign powers would have the right to special Legation Quarters in Beijing, the right to station troops in China, and occupation of parts of many other cities. They inflicted complete “disenchantment” on the once secluded and sacred Forbidden City, opening it to ambassadors, tourists, and photographers. From the first efforts of the British to open ports to trade in the early-19th century to the complete invasion and destruction of the capital city, the imperialists seemed to have succeeded in opening all of China to view, in a spectacle that guaranteed them complete visual domination.

The British had first penetrated the massive city walls of Beijing on August 18 in order to run a railway to the Temple of Heaven and deliberately defile a Chinese cemetery. Then the Americans blasted open the gates leading to the Hall of Supreme Harmony within the palace. The armies marched straight through doorways formerly restricted to the emperor himself, to reinforce open access to all forbidden areas.

|

|

|

| |

“East and West: A Group of Officers at the Gate of the Forbidden City, Peking.

A correspondent writes:—‘Whatever may be the jealousies felt in Diplomatic quarters and fostered by the Press of rival Powers, the officers of the International troops are on the best of terms, fraternising together most amicably.’”

The Graphic, December 8, 1900

Artist: Gordon Browne, R.I.

[graphic_1900_065]

|

|

| |

“Honoring the Commander of the expedition, Count Waldersee, the 9th U.S. infantry regiment lines up before the Meridian Gate of the Forbidden City. In the foreground are American minister to China Edwin Hurd Conger, his wife Sarah Pike Conger, and his family, who were rescued by the Boxer expedition.”

Stereograph (detail), ca. 1901

Source: Wikimedia

[us_1901_9thUSRegtSacredGat]

|

|

| |

“Strange Spectacle in China’s Forbidden City.

Mandarins and palace attendants serving tea, fruits, and nuts to the victorious officers of the Allied forces who had just desecrated the sacred city.— Drawn for ‘Leslie’s Weekly’ by Its Special Artist in China, Sydney Adamson, Who Was the Only American Artist Present.”

Leslie’s Weekly, 1900

[leslies_1900_v91_4_011]

| |

| |

On August 28, 1900, the foreign armies staged a triumphal march into the heart of the Imperial city. Photographs recorded the victory, and a 21-gun salute emphasized this final phase of the punishment of the Qing court. The goal of the imperial powers was to desecrate the central space of the Qing rulers and to humiliate its pretensions to occupy the cosmic center.

The Qing government protested the invasion, but had to give in when the foreign armies threatened to destroy the Forbidden City. The foreigners, however, promised not to occupy the Forbidden City permanently and to allow the Qing court to return.

|

|

| |

“A Memorable March Through the Gates of the Forbidden City at Peking.

The Allied forces, by this act, emphasized the utter humiliation and defeat of the Chinese Boxers. This was the first time that a hostile army had ever entered the inclosure.”

Leslie’s Weekly, 1900

Artist: Gordon H. Grant

[leslies_1900_v91_3_014]

|

|

| |

“The Parade Through Peking’s Imperial Palace”

Harper’s Weekly, 1900

[harpers1900_12_002]

|

|

| |

Headline, left: “Foreign Troops Passing Out of the Forbidden City.”

Headline, right: “Inside the Forbidden City.”

Harper’s Weekly, 1900

[harpers1900_12_003]

|

|

| |

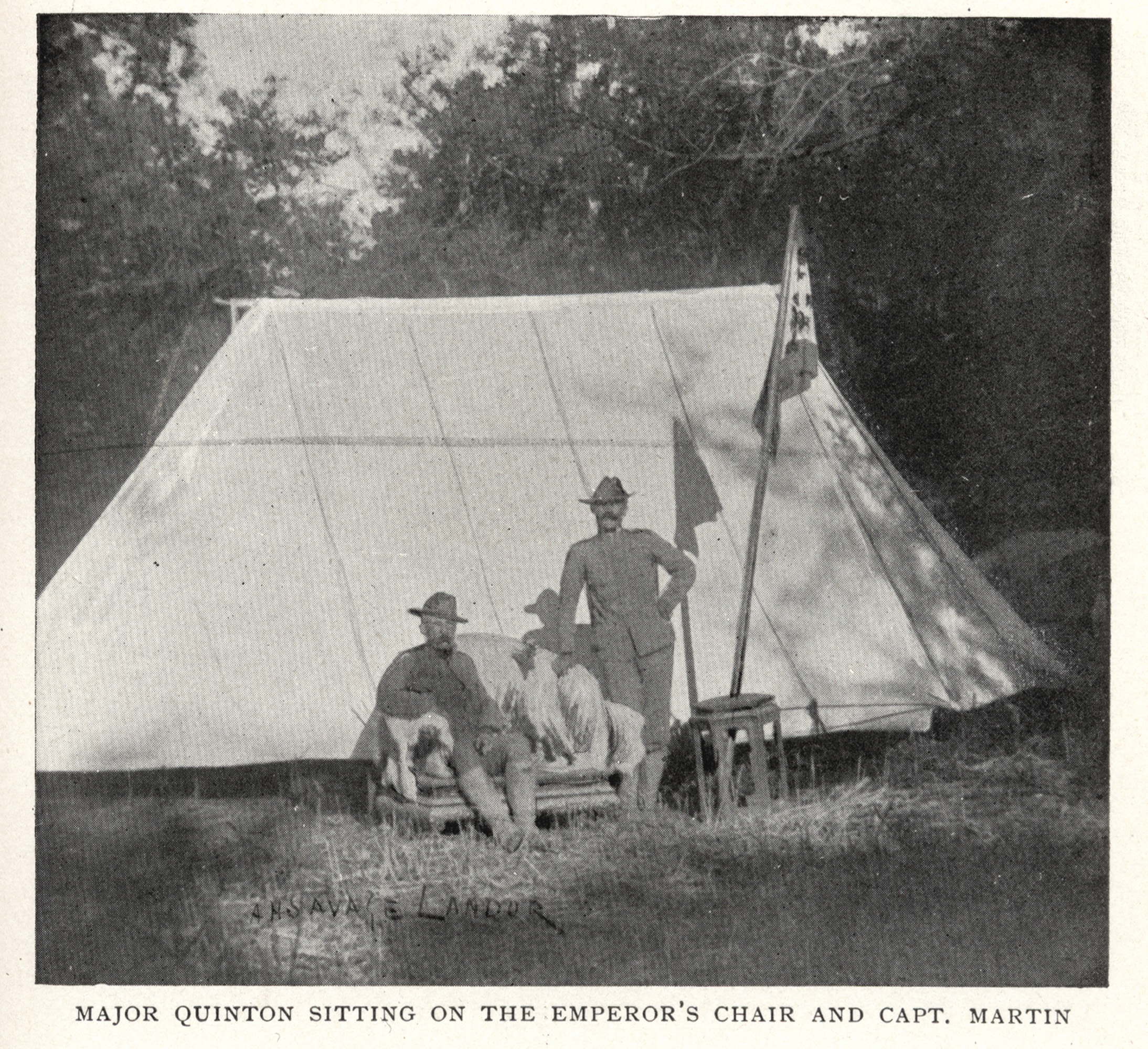

Loot

Looting of the treasures of the palace followed soon after. All the foreign armies were gripped by “loot fever,” according to contemporary descriptions. Foreigners had already looted China’s Summer Palace after the Second Opium War of 1860, but this second round was more extensive and unrestrained. Soldiers had looted everything they could along the march from Tianjin to Beijing, and now they extended their sweep to include shopkeepers in Beijing. Commanders intervened to make the looting more systematic by establishing prize committees to hand out the spoil in proportion to rank and race. Public auctions redistributed many of the goods to willing buyers, Chinese and Western. Missionaries, too, moved through villages confiscating bullion for the benefit of Christian converts. The ultimate destination of this treasure is unclear, but much of it ended up in British regimental halls and the major museums of the Western countries and Japan.

|

|

|

| |

“Major Quinton Sitting on the Emperor’s Chair and Capt. Martin”

Photograph from China and the Allies (1901)

by Henry Savage Landor

[1901_ChAllies_2267]

|

|

| |

“The Allied Troops in Peking:

an Auction Sale of Loot

When the International troops entered Peking, the city was looted by the men, but the British soldiers were not allowed to loot indiscriminately. All inhabited houses were respected, and so too was the property of all Chinese known to be friendly. The loot was put up to auction and the proceeds were given to the prize fund for soldiers. The auction sales are always crowded, people of all nationalities being present. British officers are among the principal buyers. Though prices are fairly high, grand bargains are made sometimes.”

The Graphic, December 15, 1900

(detail, right)

[graphic_1900_072b]

|

|

|

| |

“The Division of Loot at Tu-Liu, September 11, 1900.

The Building on the Left is the Pawn-Shop. In the Inner Court, under the Superintendence of General Dorward, Loot was divided among the British Officers. The Hindoo Soldiers and Servants are waiting outside to carry away the Booty of their Masters.”

Harper’s Weekly, November 10, 1900

[harpers1900_09-12_023]

|

|

| |

Occupation: Trials, Executions and Punitive Expeditions

The expeditionary force itself committed much random slaughter of innocent Chinese civilians, making no distinction between Boxers and ordinary peasants. Torture and immediate execution by firing squads continued months after the occupation of Beijing. Punitive expeditions all through Zhili province continued into the next year. The soldiers razed temples, ransacked tombs, and destroyed thousands of homes. In Baoding city, where 15 Americans and British missionary adults and children had been killed, the armies insisted on the beheading of the Qing officials in command of the local garrison, and they destroyed the city wall and temple. The executions created a public spectacle, intended to inflict retribution on the Chinese state and people for the killings of Westerners by the Boxers. The Western imperialist code of justice supported a violent civilizing mission designed to force the Chinese to abandon their savage ways and recognize the virtue of their conquerors.

|

|

|

| |

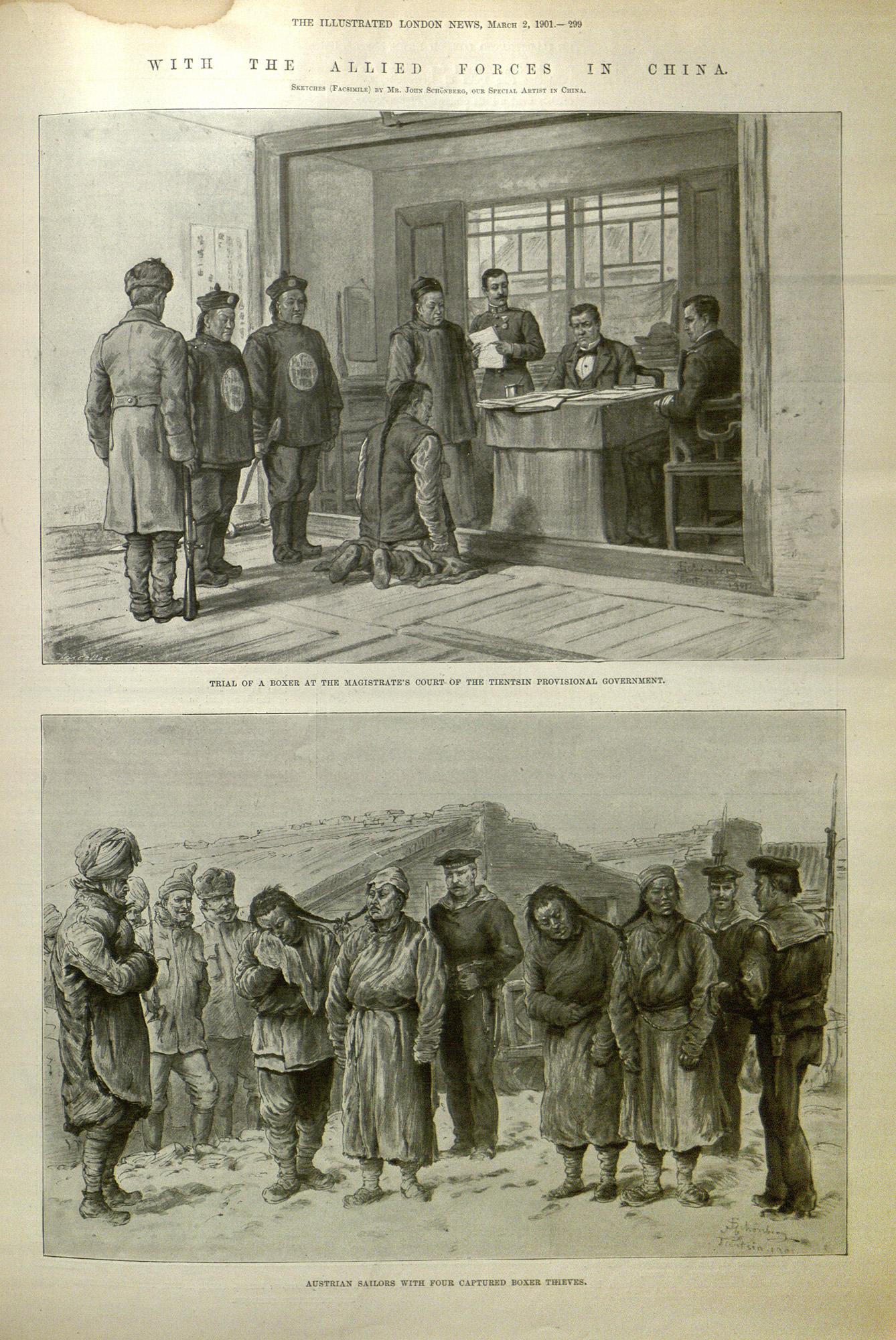

“With the Allied Forces in China. Sketches (Facsimile) by Mr. John Schoenberg, our Special Artist in China.”

Caption (image, top): “Trial of a Boxer at the Magistrate’s Court of the Tientsin Provisional Government.”

Caption (image, bottom): “Austrian Sailors with Four Captured Boxer Thieves.”

The Illustrated London News, March 2, 1901

[iln_1901_v1_012]

|

|

| |

“The Allies in China: A French Court-Martial in Peking.

On the arrival of the allied troops in Peking, the city was divided into sections to be policed by the different European nationalities. Prisoners suspected of complicity with the Boxer movement were brought in

and tried

by court-martial.”

The Graphic, March 1, 1901

[graphic_1901v1_023]

|

|

| |

The following two graphics show the shift from the use of firing squads by Allied troops to the use of Chinese executioners under Allied supervision. The Allied powers, fearing that their own soldiers would become brutalized by enacting executions, decided to delegate this role to Chinese swordsmen, as they believed, falsely, that beheading was a common form of punishment in China.

|

|

|

| |

“The Crisis in China: The Administration of Justice in Tientsin

A Correspondent writes:— ‘The Provisional Government of Tientsin sentenced four Chinamen to death, the penalty being executed the first week in September. Two were arrested by French guards in the part of the city allotted to them to patrol, and the other two were arrested by Japanese soldiers. The two former were guilty of looting from other Chinese with violence. The two latter were Boxer captains. The latter were beheaded by the Japanese, the other two shot by the French soldiers. Mr. Emmons, resident of Tientsin, and Mr. Denby, son of Colonel Charles B. Denby, are the judges for the Provisional Government’”

The Graphic,, 1900

[graphic_1900_058]

|

|

|

| |

“The Crisis in China: The Execution of Three Anti-Foreign Officials

in Paoting-Fu

The International Commission, which was given full powers of life and death as regards the rebels at Paoting-fu, sentenced three principal offenders to death. These were Fentai, who did nothing to protect the Europeans and Christians, or to prevent the massacre of missionaries; the Tartar Governor who encouraged and organised the Boxer movement; and the Colonel of Cavalry, Wang Chen Quan, who allowed the missionary Bagnall, his wife, and little girl to be massacred when they sought protection in his camp.”

The Graphic, January 5, 1901

Artist: F. De Haenen, “from a sketch by a British officer”

[graphic_1901v1_004]

|

|

| |

“Événements de Chine.

Exécution à Pao-Tin-Fou”

Le Petit Journal Supplément Illustré No. 531, January 20, 1901

Source: Widener Library, Harvard University

[lpji_1901_01_20th_2]

|

|

| |

Occupation Troops

Most descriptions of the activities of Western troops in Beijing, however, did not stress executions, but treated the experience as a time of exotic travel and entertainment. They repeated earlier descriptions of China as a bustling, crowded commercial society; but now Westerners dominated the city, free of restrictions from the imperial officials. Troops could ride and riot around the city at will.

|

|

|

| |

“With the Allies in China: Soldiers and Sailors Amusing Themselves in a Crowded Thoroughfare in Peking

Our Special Artist writes:—The road leading out of the south entrance to the Tartar City is always one of the most crowded in Peking. Street merchants, donkey-boys, camel trains, rickshaws, and a continuous stream of Peking carts, following one another like omnibuses in the Strand, jostle each other all day. A favourite amusement of the soldiers and sailors of the Allied troops is to have donkey rides. The troops in their varied uniforms, Western and Oriental, add greatly to the picturesqueness of the scene, but also rather aggravate the congested state of the traffic.”

The Graphic, April 27, 1901

[graphic_1901v1_030]

|

|

| |

“A Tien-tsin.

Rixe entre Allemands et Auxiliaires Anglais”

Translation: “In Tianjin. Brawl between German and English Auxiliary”

Le Petit Journal Supplément Illustré No. 580, December 29, 1901

[lpj_1901_12_29_widener_bra]

|

|

| |

Signing of Protocol & Reparations

The Final Protocol of September 7, 1901 delivered the demands of the Western powers to the Qing government. They demanded the execution of Qing officials who supported the Boxers, apology missions to the foreign powers, and a new form of foreign relations in which foreigners stood at an equal level to the court. The protocol required payment of an indemnity of 450 million taels of silver over a period of 39 years to the eight invading nations. By 1927, most of the payments had been revoked or channeled back into education and other programs in China.

|

|

| |

Photo composite of the signing of the Boxer Protocol, September 7, 1901

[graphic_1901v1_004]

|

|

| |

The following image shows the poor Chinese farmer weighted down with heavy indemnities, while the "rising tide of extinction" threatens his life. Some Westerners who supported the expedition criticized the high price of the indemnities, and they feared for the survival of the Qing dynasty under this burden. They did not know that the Qing would collapse in only ten years under the assault of domestic nationalism.

|

|

| |

“China—‘Is this Christianity?’”

Judge, May 4, 1901

[1901_04May_Judge_IsThisChri]

|

|

| |

The Beginning of the End: The Last Decade of the Qing Dynasty

After submitting to the humiliation of the Boxer treaties, and formally apologizing to Kaiser Wilhelm for the murder of Baron von Ketteler, the Qing court was allowed to return to Beijing. The Western powers, fearing the mutual conflict between imperialists that could break out at any time, had an interest in keeping the Qing dynasty alive. But a rapid series of events, including the death of many of the major world actors, undermined the stability both of the Qing dynasty and the global world order. Less than a decade after the Boxer intervention, four of the world leaders involved in the events of 1900 passed away. Queen Victoria, Li Hongzhang, President McKinley (assassinated in September 1901), and the Empress Dowager Cixi had directed this global clash from their positions at the top of their governments, often facing little opposition. When they were gone, more turbulent popular forces arose challenging the legitimacy of the negotiated settlements and setting the stage for more violent popular uprisings.

Prince Chun, the 18-year-old brother of the Qing emperor, was appointed special ambassador by the Qing court to Germany to offer the government's regrets for the murder of Baron von Ketteler in 1900. He met Kaiser Wilhelm and toured Europe afterwards, becoming the first member of the imperial clan to travel abroad. The empress dowager was suspicious of him because of his ties to foreign powers, but his son, Puyi, born in 1906, inherited the throne as the last emperor of the Qing in 1908.

|

|

|

| |

“The Chinese Expiatory Mission to Germany: The Kaiser Receiving Prince Tchun in the New Palace at Potsdam, September 4.”

Caption (left to right): “Count Wede. Ying-Chang (New Chinese Minister to Berlin. Prince Tchun. General von Moltke. General von Ende.”

The Illustrated London News, September 14, 1901

Artist: Count von Looz, “Member of the Court”

[iln_1901_v2_005]

|

|

| |

Death of Queen Victoria (January 22, 1901)

The death of Queen Victoria, in January 1901, marked the end of the reign of Britain’s longest reigning monarch. The Queen had made few public appearances since the death of her husband in 1861, but the celebration of her Golden Jubilee, in the 50th year of her reign, and the Diamond Jubilee, in 1897, supported British confidence in the unending supremacy of the empire and its monarchical tradition. At her death, British forces were still at war in China and South Africa, and faced rivalries from many other imperial powers.

Britain soon had to diverge from its foreign policy of “splendid isolation” from continental politics and sought alliances with Japan in 1902, and France and Russia shortly after. The end of the Victorian era seemed to mark a retreat from arrogance and puritanical restraint, and new uncertainty about the future.

Death of Li Hongzhang (November 7, 1901)

Li Hongzhang’s death in the same year also marked a time of transition in China from forward-looking reform to anxious defensiveness. Li had been one of the most dynamic provincial officials since the 1860s, when he had organized an army to fight the Taiping rebellion, and he had always collaborated fruitfully with foreigners. When he rose to become Governor-General of Zhili, the province that included Beijing, he worked to dampen anti-foreign sentiment, and he became the most powerful person directing Qing foreign policy.

He had negotiated major treaties with the British, the French, and the Japanese, and he vigorously promoted the strengthening of China’s military forces as well as education of Chinese abroad. Foreigners praised him as their most reliable counterpart, but he constantly faced opposition both within the court and from nationalists arguing that he had sold out China’s interests for personal gain. His death initiated a period of rising nationalist mobilization which soon turned against the Qing court itself, leading to the downfall of the Qing dynasty in 1911.

Return of the Empress Dowager (January 1902)

The empress dowager and her court returned to Beijing in 1902. The remaining years of her reign, until she died in 1908, showed a new openness to foreign eyes. She held an unprecedented number of audiences with foreign ministers: nearly 200 of them from 1902 to 1911.

She expanded her contacts to include not only the male envoys, but their wives and even their children. She had many photographs taken of herself with her court ladies and with visiting Western women, to demonstrate that she and her court had become a “modern” monarchy, just like that of Queen Victoria, her British counterpart. Yet many visitors still regarded the Qing as the archetypical example of “Oriental Despotism,” now completely accessible for visitors and tourists alike.

|

|

|

| |

“Triumphal Return of the Emperor and Empress Dowager to Peking. Spectacular scene at the Chien-Men Gate when they entered the temples to offer thanks—the wall crowded with foreigners”

Leslie’s Weekly, January 23, 1902

[1902_23Jan_LesliesWeekly_Re]

|

|

| |

End of the Boer & Filipino Wars (1900–1902)

The Boer War in South Africa (1899–1902) featured prominently in illustrated magazines alongside stories of the Boxer expedition. Both the Boers, descendants of Dutch settler farmers called Boers by the British, and the Chinese peasantry appeared as savages resisting benevolent British imperial rule. In its final stages, the Boer war petered out into a sporadic guerrilla war by the Afrikaner farmers against increasingly well-organized British forces. Officially, the U.S. war in the Philippines ended in 1902, but guerrilla resistance continued in some regions for another decade. In both places, the imperial powers enacted new repressive policies of counterrevolutionary warfare. The British created a linked system of blockhouses to protect their supply lines, garrisoned by large numbers of troops. At the same time, they stretched barbed wire across the countryside to block Boer movements of humans and cattle. They enacted a scorched earth policy to deprive all the inhabitants of the guerrilla region of means of survival. They created internment camps, or “concentration camps,” to cut off access of Afrikaner fighters to the civilian population. All these tactics mirrored those used by the United States in its war against the Filipino resistance. Popular media celebrating British and American victories often depicted the Boers as savage peasants comparable to the Boxers and Filipinos. The three major resistance movements still remained linked in the popular imagination.

Conclusion

The Boxer intervention marked a decisive turning point in the politics of imperialism and in the relations between colonial and semi-colonial countries and the dominant powers of the West and Japan. The image below shows that the eight nations had achieved temporary unity in their alliance against China, but soon after their victory over the Qing, they fell into rivalry with each other.

|

|

|

| |

“The Real Trouble Will Come with the ‘Wake’”

Puck, August 15, 1900

Artist: Joseph Ferdinand Keppler

[puck_1900_740_yale]

|

|

| |

The growing tensions between Britain, France, Germany, and Russia over influence in the Balkans, along with the decline of the Ottoman empire and further conflict in Africa, generated the series of competitive alliances which would soon break out in World War l. Soon the Western powers would turn the military technologies tested in the colonial periphery against each other, and each nations’ popular media would portray Western enemies with the same racial imagery of savagery that they had applied to non-Western peoples. Japan continued to rise in strength in the first decade of the 20th century, defeating Russia in 1905 in a shocking victory that demonstrated its right to premier imperial status.

China, despite a last ditch reform effort by the Manchu regime, fell into further weakness, and the Qing empire finally collapsed after the outbreak of a military revolt in October 1911. This first decade of the 20th century initiated processes of war, racial mobilization, media popularization, and economic advance that continue to shape our times.

|

|

| |

|

|

|