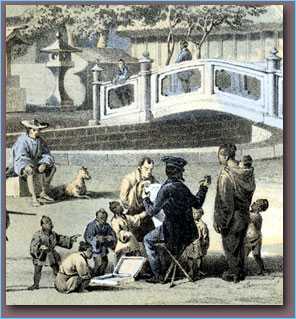

| Drawings and water colors, largely by William Heine, were reproduced

in various forms as woodcuts and lithographs. Many of these reproductions

cite “drawn from nature by Heine; figures by Brown.” This

reference is to Eliphalet Brown, Jr., whose daguerreotypes of Japan and

the Japanese were subsequently lost in a fire. The interplay between these two artists and art forms was clearly extensive, though its details are not completely clear. |

| Heine not only placed himself in several of his illustrations... |

| ...here, surrounded by curious Japanese near a shrine in Shimoda... |

| ...but also placed Eliphalet Brown in one of his illustrations... |

| ...leaning on his camera in the act of creating a daguerreotype. |

| The resulting image—which survives only as recreated in a lithograph—captures three men in Okinawa seated beneath a tree, seemingly at peace with the world. |

| Click here to see variations of this detail—Photographing a Courtesan—from several versions of the “Black Ship Scroll.” |

| As it happens, Japanese painters also left a record of Eliphalet Brown and his “magic mirror” camera. Here Brown and two assistants photograph a courtesan “for the American king.” This daguerreotype has disappeared, and no lithograph was ever made to tell us what the camera saw. |

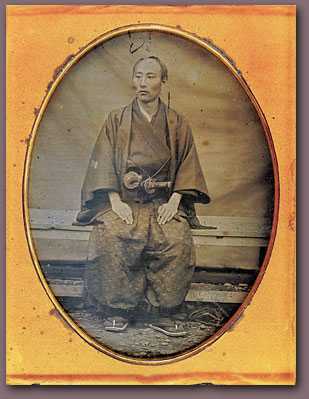

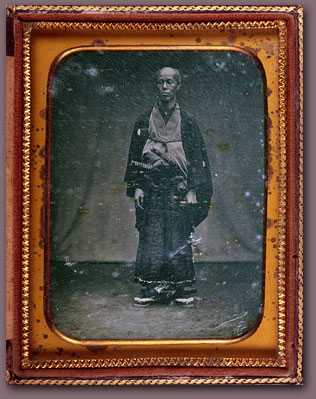

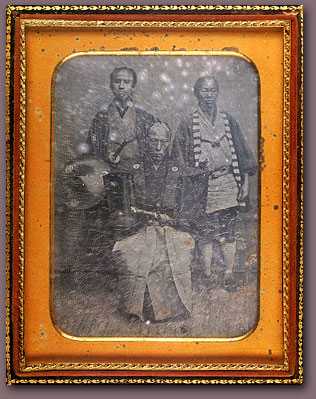

| A handful of photos from the Perry mission

did survive. The daguerreotype process demanded the subject hold still for many minutes. (Notice the support at the feet of the standing samurai.) |

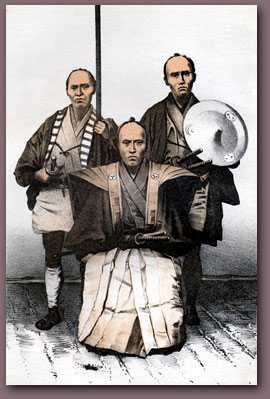

| In this daguerreotype, the seated prefect of Hakodate holds center stage, while two retainers stand behind him. The prefect maintained proper appearance by reversing his sword and garment for the camera; his attendants did not bother to do so. |

| A samurai always wore his sword on the left,

and all Japanese fold kimono left over right. Since a daguerreotype is a mirror image, subjects would have to dress in reverse to create the proper appearance. The man on the left did, the man on the right—a higher ranking samurai and interpreter for the Perry mission—did not. |

| As fate would have it, the prefect’s fastidiousness

did not carry over to the wider world of publishing. The official Narrative

contains a lithograph of the same three men in which the two aides have

changed sides, but so have the prefect’s sword and kimono-fold. Inexplicably, all three men now appear improperly dressed and armed. |

| All but a handful of the more than four-hundred

daguerreotypes taken during the Perry mission were destroyed in a fire. Fortunately, many lithograph copies remain as a record of these lost images. |

|

In subsequent years, photography would gradually render paintings, woodblock

prints, lithographs, and the like outdated as ways of visualizing other

peoples and cultures for mass consumption. Immediately following Perry’s opening of Japan, photographers hastened to produce a rich record of the people and landscapes of the waning years

In this regard, Eliphalet Brown, Jr.’s daguerreotypes and the portraits copied from them were a harbinger of what was to come. |

|

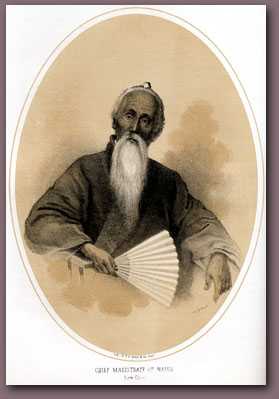

Lithographs based on daguerreotypes by Eliphalet M. Brown include: Mother

and Child, Simoda; Japanese Women; Chief Magistrate, Napha; Afternoon

Gossip, Lew Chew; Bungo or Prefect Hakodadi. Public Bath at Shimoda by

William Heine. Book illustrations from Francis L. Hawks’ Narrative

of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan,

Performed in the Years 1852, 1853, and 1854, under the Command of Commodore

M. C. Perry, United States Navy, by Order of the Government of the United

States, Vol. 1. Washington, D. C., 1856. Photographing a Courtesan, detail from the 1854 “Black Ship Scroll,” Honolulu Academy of Art. Daguerreotypes by Eliphalet M. Brown, 1854, include: “Tanaka Kogi,” Collection of Shimura Toyoshirou; “Namura Gohachiro,” Bishop Museum; “Endo Matazaemon & His Attendants” © Yokohama Museum of Art. Lithographs based on daguerreotypes by Eliphalet M. Brown from Francis L. Hawks’ Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, Performed in the Years 1852, 1853, and 1854, under the Command of Commodore M. C. Perry, United States Navy, by Order of the Government of the United States, Vol. 1. Washington, D. C., 1856. On viewing images from the historical record: click here. Black Ships & Samurai © 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology A project of professors John W. Dower & Shigeru Miyagawa Design and production by Ellen Sebring, Scott Shunk, and Andrew Burstein |