| On July 8, 1853, residents of Uraga on the outskirts of Edo, the sprawling

capital of feudal Japan, beheld an astonishing sight. Four foreign warships had entered their harbor under a cloud of black smoke, not a sail visible among them. They were, startled observers learned, two coal-burning frigates towing two sloops. Commodore Perry had arrived to force the long-secluded country to open its doors to the outside world. |

| The “Demon” Ship |

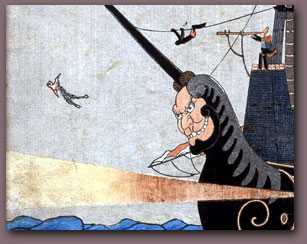

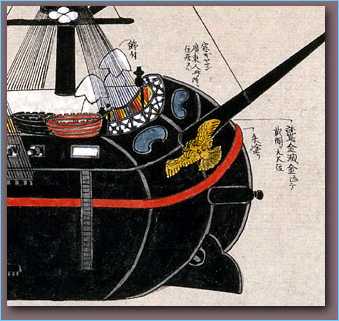

| Japanese artists, like the Americans, also gave free rein to their imaginations by depicting the steam-driven black warships—almost literally—as Darkness Incarnate. |

| The warship was pitch black and the figure- head on the prow was a leering monster. |

| Ominous clouds of smoke belched from the smokestack. |

| Startled Japanese quickly dubbed the American

fleet the “Black Ships.” |

| Cannon bristled above an elegant paddlewheel, portholes glowered like the eyes of an apparition, and gunfire streaked from bow and stern like a searchlight. |

| In a demonic sister ship, art spilled over

into the realm of caricature and cartoon. The stern of the vessel has

been turned into the eyes, nose, mouth of a monster. How should we interpret

this? Is this meant to reflect the monstrous nature of those who came with the ship? Or, could it reflect the practice common among Asian seafarers of the time to place huge demonic faces on vessels to ward off evil spirits and ensure safe passage? The answer, perhaps, is a mixture of both. |

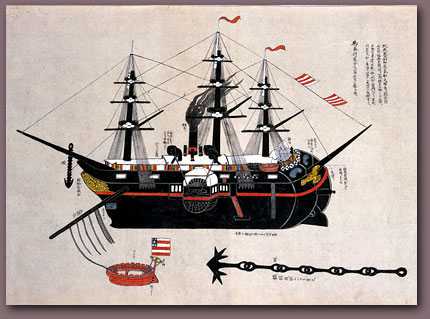

| The black ships did not merely

alarm the Japanese; they also fascinated them. Most artists portrayed the ships in a straight-forward manner from the same perfect-profile perspective beloved by the Westerners. While both approaches were considered “realistic,” they convey different impressions. |

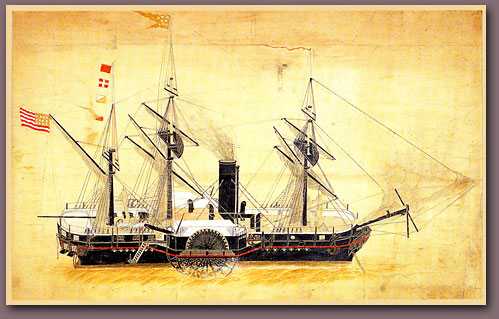

| In contrast to the American oil painting of the Powhatan seen elsewhere, this Japanese watercolor of the same ship reveals how pictorial “realism” may vary depending not only on the viewer but also on the medium used. |

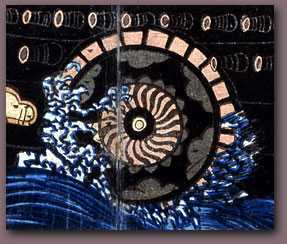

| In this 1854 rendering of one of the black ships,

the artist has introduced a traditional stylized “chrysanthemum” design into the paddle wheel. |

| Though realistic and carefully labeled, a subtle “face”

seems to be suggested in the stern of this drawing, reminiscent of the more imaginary renderings. This is yet another illustration of the Powhatan. |

| Panoramic views of the American squadrons

were often designed to convey details concerning not only the black ships

but also the surrounding terrain. This 1854 map of the harbor at

Shimoda depicts six of Perry’s gunboats resting at anchor. Place names (and ships) appear right-side up, upside down, and sideways—a convention that developed from maps being rotated as they were read. |

|

“A Foreign Ship,” woodblock print, artist unknown, © Nagasaki Prefecture. “Black Ship and Crew,” watercolor on paper, ca. 1854, Ryosenji Treasure Museum “The Powhatan,” hanging scroll, 1854 or later, Peabody Essex Museum “Black Ship at Shimoda,” painting, 1854, Ryosenji Treasure Museum “Black Ship painting,” 1854, Ryosenji Treasure Museum Map detail from the 1854 “Black Ship Scroll,” Honolulu Academy of Art. On viewing images from the historical record: click here. Black Ships & Samurai © 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology A project of professors John W. Dower & Shigeru Miyagawa Design and production by Ellen Sebring, Scott Shunk, and Andrew Burstein |