| |

|

S.

Wells Williams S.

Wells Williams |

Okinawan

official |

|

Shiryo

Hensanjo, University of Tokyo Shiryo

Hensanjo, University of Tokyo |

from

the official Narrative |

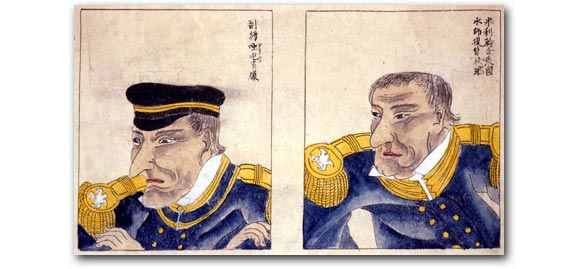

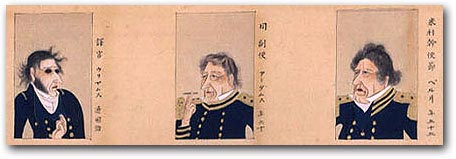

As already seen in their diverse renderings of Commodore Perry, Japanese

artists did not hesitate to resort to outright fantasy when drawing

portraits of the foreigners. Even when they were ostensibly drawing

“from life,” their attempts to capture the spirit or personality

of their subjects gave a touch of caricature to the resulting portrait.

We see this in an ostensibly realistic pair of paintings of Perry

and Commander Henry Adams, his second-in-command, for example,

as well as in anonymous woodblock portraits of a decidedly foppish

Adams and an alarmingly sharp-visaged “American Chief of the

Artillery-men.”

|

|

Perry

(right) and Adams, ink and color on paper, 1854 Perry

(right) and Adams, ink and color on paper, 1854

Ryosenji Treasure Museum

|

|

Left:

“American Chief of the Artillery-men” Left:

“American Chief of the Artillery-men”

Right: “The North American Adjutant General (Adams)”

woodblock prints, ca. 1854

Peabody Essex Museum

|

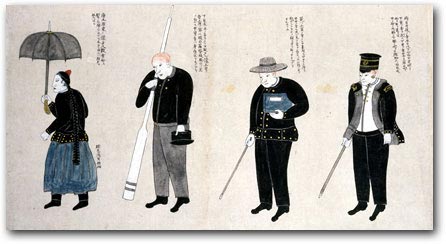

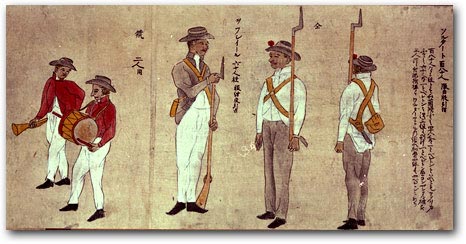

Full-figure

renderings of the foreigners as they were observed in Kurihama or

Yokohama or Shimoda or Hakodate followed the same free style. Often

these figures were lined up in a row like a droll playbill for a cast

of characters who had chosen to strut their stuff on the Japanese

stage.

|

|

“Pictorial Scroll of Black Ships Landing at Shimoda” (detail)

Ryosenji Treasure

Museum |

“Pictorial Record of the Arrival of Black Ships” (detail)

ca. 1854

Ryosenji Treasure Museum |

|

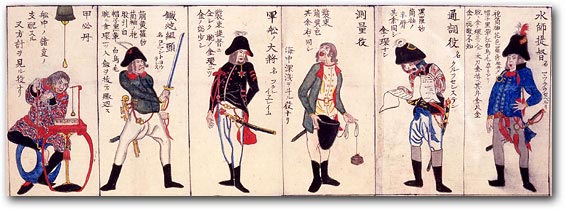

A

particularly dramatic cast of characters accompanied one of the monstrous

black ships introduced earlier, in the form of a gallery of nine individuals.

In addition to Perry, the accompanying text identified them (right

to left) as an interpreter, the crewman who sounded the ocean’s

depth, a high officer, the chief of the “rifle corps”

(marines), a navigator, a marine, a musician, and a crewman from a

“country of black people,” usually called upon “to

work in the rigging or dive in the sea.” Colorful and idiosyncratic,

they comprised a motley crew indeed.

|

|

Detail from

“Black Ship and Crew”

ca. 1854

Ryosenji Treasure Museum

|

|

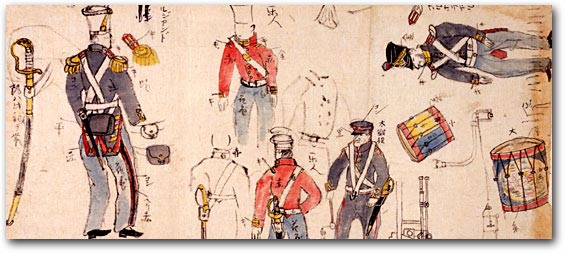

Some

sketches by Japanese artists were clearly drawn from direct observation,

with close and annotated attention to every article of attire and

piece of equipment.

|

|

|

From

an artist’s sketchbook, 1854 From

an artist’s sketchbook, 1854

Shiryo Hensanjo, University of Tokyo

|

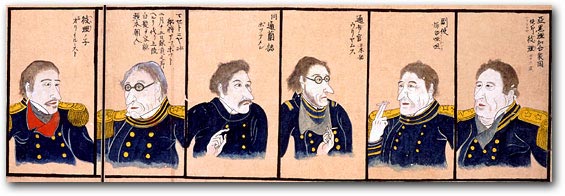

The

most “realistic” run of portraits of the Americans dates

from March 8, 1854, when Perry landed in Yokohama to initiate his

second visit. Commissioned by the daimyo of Ogasawara, the original

sketches were drawn by Hibata Osuke, a performer of classical Noh

drama who studied under the famous woodblock artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

With some difficulty, Hibata managed to situate himself in the midst

of that day’s activities and record a great variety of subjects

and events.

Other artists subsequently copied his keenly observed renderings of

the commodore and five others: Commander Adams; Captain Joel Abbott;

S. Wells Williams, a missionary from China who knew some Japanese;

a Dutch-Japanese interpreter named Anton Portman (communication often

required using Dutch as an intermediary language between English and

Japanese); and Perry’s son Oliver, who served as his personal

secretary. The posing was highly stylized—all in half-profile—and

each subject possessed the prominent nose that set Caucasians apart

in Japanese eyes. At the same time, each was unmistakably imbued with

individuality.

|

|

Two

colored renderings based on Hibata Osuke’s 1854 sketches of

Perry and five others. From right to left (above): Commodore Perry, Commander Adams, English-Japanese

translator S. Wells Williams, translator Anton Portman, Captain Joel Abbot, and

Perry’s son Oliver Two

colored renderings based on Hibata Osuke’s 1854 sketches of

Perry and five others. From right to left (above): Commodore Perry, Commander Adams, English-Japanese

translator S. Wells Williams, translator Anton Portman, Captain Joel Abbot, and

Perry’s son Oliver

Shiryo Hensanjo, University of Tokyo

(above) Chrysler Museum of Art (below)

|

|

|

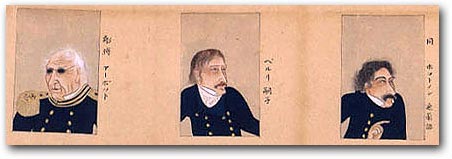

The

Americans brought a very different—and very recent—perspective

to their individual portraits. Where Japanese depictions of the foreigners

essentially came out of well-established rhetorical and pictorial

conventions, the Americans brought the eye of the camera. Two different

photographic processes—calotype and daguerreotype—had

been introduced in the West in 1839, and the latter dominated the

world of photography into the 1850s.

Daguerreotypes were distinguished by their grainless and exceptionally

sharp images, but had the disadvantage of producing a single, fragile,

non-reproducible original. There was no negative, and thus no possibility

of making multiple copies. Producing one of these plates involved

a complex (and toxic) chemical process, and was exceedingly time-consuming.

Although a daguerreotype camera was obtained by an enterprising Japanese

as early as 1848, it was the Perry mission that actually made the

first photographic portraits of Japanese.

The entertaining “Black Ship Scroll” rendering of three

Americans photographing a courtesan (seen in the previous section)

actually depicts the mission’s chief photographer, Eliphalet

Brown, Jr., and his assistants. Although Brown is known to have taken

more than 400 daguerreotypes of scenery and individuals,

all but a handful have been lost. Some were given to the individuals

who were photographed, and those brought back to the United States

were destroyed in a fire while the official report was being prepared

for publication.

The few originals that have come down to us—mounted in the heavy

gilt frames that commonly enhanced and protected these precious images—portray

samurai. Among them are depictions of Namura Gohachiro, an interpreter

summoned from Nagasaki; Tanaka Mitsuyoshi, a low-ranking guard in

Uraga; and officials in the new treaty ports of Hakodate and Shimoda.

|

|

Tanaka

Mitsuyoshi, a low-ranking guard in Uraga. Daguerreotype by Eliphalet Brown, Jr., 1854 Tanaka

Mitsuyoshi, a low-ranking guard in Uraga. Daguerreotype by Eliphalet Brown, Jr., 1854

Collection of Shimura Toyoshiro

|

Namura

Gohachiro, an interpreter summoned from Nagasaki. Daguerreotype by

Eliphalet Brown, Jr., 1854 Namura

Gohachiro, an interpreter summoned from Nagasaki. Daguerreotype by

Eliphalet Brown, Jr., 1854

Bishop Museum of Art

|

The

posed portraits of Namura and Tanaka, similar at first glance, have

subtle stories to tell. Barely visible behind Tanaka’s feet,

for example, is the foot of some sort of wooden stand—believed

to be a prop used to assist subjects in holding steady for the long

exposure that the daguerreotype process demanded. Additionally, whereas

Tanaka appears as the eye would see him (kimono folded left over right,

and swords carried on the left), Namura confronts us in reverse image

(kimono folded right over left, and swords on the right—where

a samurai, trained to fight right-handed, would be unable to draw

quickly). Since the daguerreotype produced a mirror image, it is Tanaka

who is the anomaly. To appear properly in the photo, he folded his

garment and mounted his sword improperly. Namura did not do this.

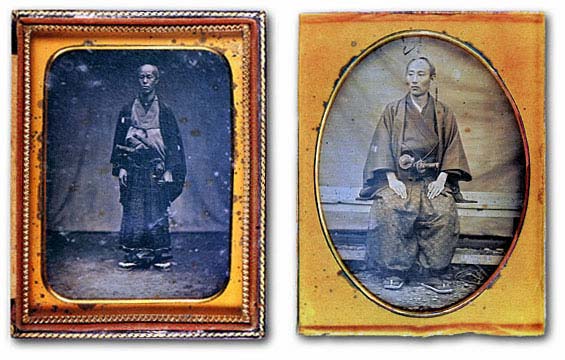

Another of Brown’s surviving “magic mirror” daguerreotypes

exposes, in and of itself, this same issue of how to pose. In this

daguerreotype, which has deteriorated over time, the seated bungo

or prefect of Hakodate holds center stage, while two retainers stand

behind him. Like Tanaka, the prefect maintained proper appearance

by reversing his sword and garment for the camera; and, like Namura,

his attendants did not bother to do so. As fate would have it, however,

the prefect’s fastidiousness did not carry over to the wider

world of publishing. The official Narrative contains a lithograph

of the same three men—apparently based on another daguerreotype

taken at the same sitting—in which the two aides have changed

sides, but so have the prefect’s sword and kimono-fold. Somewhat

inexplicably, all three men now appear to be improperly dressed and

armed.

|

|

Endo

Matazaemon, a local official in Hakodate, and his attendants. 1854

daguerreotype by Eliphalet Brown, Jr. and a near mirror-image lithograph of the three

men from the official Narrative of the Perry mission published in 1856 Endo

Matazaemon, a local official in Hakodate, and his attendants. 1854

daguerreotype by Eliphalet Brown, Jr. and a near mirror-image lithograph of the three

men from the official Narrative of the Perry mission published in 1856

Yokohama Museum of Art

|

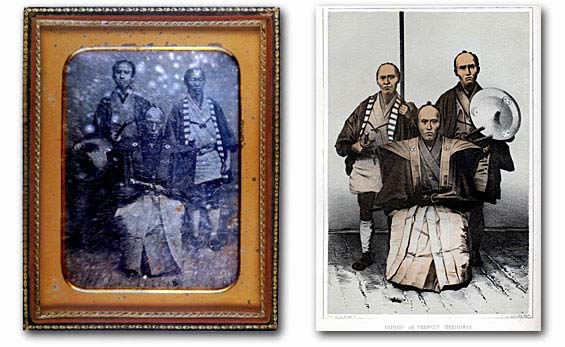

Despite

the loss of Brown’s original work, the official record actually

contains a number of woodcut and lithograph portraits that are explicitly

identified as being based on his daguerreotypes. Thus, the camera’s

eye remains, even though the photographs themselves have disappeared.

Its focus falls not just on samurai, but on anonymous commoners as

well—and not just on the Japanese, but also on residents of

the Ryukyu (“Lew Chew”) Islands, which did not formally

become part of Japan until the 1870s.

|

|

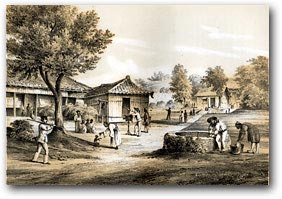

Like the official illustrations that included artists sketching and

painting, the Narrative actually gives us a subtle “double exposure”

of the photographer at work. Thus, close scrutiny of a bucolic illustration

by Heine titled “Temple at Tumai, Lew Chew” reveals Brown

at stage center preparing to photograph several seated figures.

|

| |

|

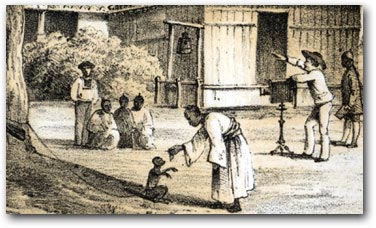

“Temple at Tumai, Lew Chew” with Eliphalet Brown, Jr. preparing to take a daguerreotype portrait (detail at right) “Temple at Tumai, Lew Chew” with Eliphalet Brown, Jr. preparing to take a daguerreotype portrait (detail at right) |

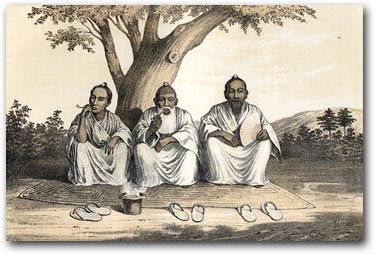

“Afternoon

Gossip, Lew Chew”

lithograph based on Brown’s daguerreotype

|

Some

twenty-plus pages later, we are treated to a charming, tipped-in lithograph

titled “Afternoon Gossip, Lew Chew,” depicting three men—surely

these very same subjects—seated on a mat beneath a tree, smoking

and seemingly at perfect peace with the world.

While

dignity pervades the individual portraits that grace the Narrative, informality such as

this is rare. Usually, those who held so still for so long—as

the slow daguerreotype process demanded—tend to seem immobilized,

almost frozen. They inhabit a world far removed from the animated,

colorful, half imagined or even entirely imagined “Americans”

we encounter on the Japanese side.

In subsequent years, the verisimilitude of photography and technical

ease of both shooting and reproducing pictures would gradually render

paintings, woodblock prints, lithographs, woodcuts, and the like outdated

and even obsolete as ways of visualizing other peoples and cultures

for mass consumption. And, indeed, immediately following Perry’s

opening of Japan, both native and foreign photographers hastened to

produce a rich record of the people and landscapes of the waning years

of the feudal regime (the Shogun’s government was overthrown

in 1868). In this regard, Eliphalet Brown, Jr.’s daguerreotypes

and the portraits copied from them were a harbinger of what was to

come. |

|

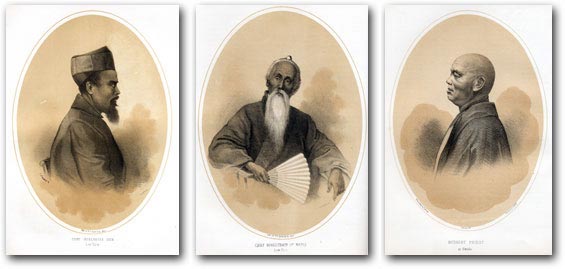

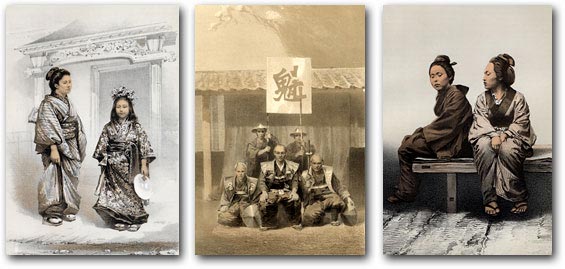

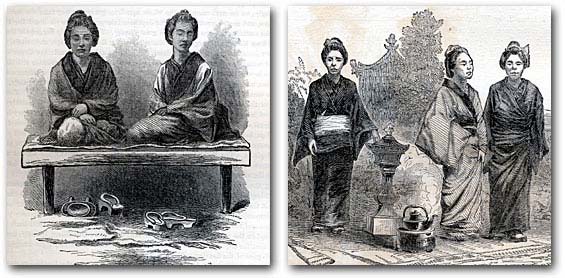

| A Gallery of Portraits

from the Official Narrative |

|

|

| Court

interpreter, Ryukyus |

Chief

magistrate, Ryukyus Chief

magistrate, Ryukyus |

Buddhist

priest Buddhist

priest |

|

| Mother

and child, Shimoda |

Prefect

of Shimoda Prefect

of Shimoda |

Women,

Shimoda Women,

Shimoda |

|

| “Priest

in Full Dress,” Shimoda |

“Prince

of Izu” “Prince

of Izu” |

Interpreters Interpreters |

|

Women

in Shimoda Women

in Shimoda

|

|

|