| |

Encounters: Facing “West”

|

The Japanese visualization of these first encounters presents a different

world. This is true not only of artwork churned out at the time, but

also of evocations of the Perry mission that artists produced in later

years. It mattered greatly, of course, that whereas the Americans

were observing the Japanese in their native milieu, the Japanese were

confronting intruders far from home.

For the Japanese, that is, the foreigners who suddenly materialized

in their waters and descended upon their soil had no context, no tactile

background. They existed detached from any broader physical and cultural

environment. Whereas Heine and his colleagues could attempt to present

“Japan” to their audience, the Japanese had only a small

number of “Americans” and their artifacts upon which to

focus.

There was, moreover, no counterpart on the Japanese side to the official

artists employed by Perry—and thus no Japanese attempt to create

a sustained visual (or written) narrative of these momentous interactions.

What we have instead are representations by a variety of artists,

most of whose names are unknown. Their artistic conventions differed

from those of the Westerners. Their works were reproduced and disseminated

not as lithographs and engravings or fine-line woodcuts, but largely

as brightly colored woodblock prints as well as black-and-white broadsheets

(kawaraban).

They also painted in formats such as unfolding “horizontal scrolls”

(emaki) that had no counterpart in the West. It was common

for such scrolls to be 20 or 30 feet long, and in some cases they

inspired variant copies. Many of these artists drew no boundary between

direct observation and flights of imagination. On occasion, tension

permeated their images—and no wonder. Their insular way of life,

after all, had been violated and would never be the same. Although

one might (and some did) pretend otherwise, it was obvious where the

preponderance of power lay.

|

|

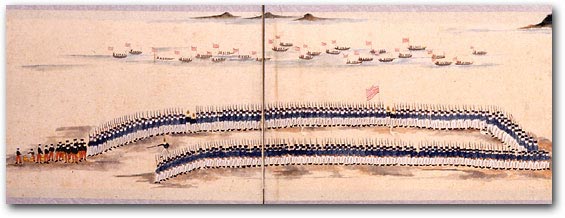

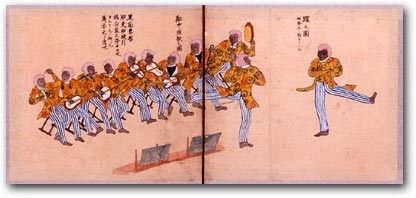

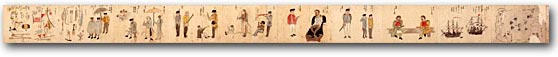

Perry’s

troops landing in Yokohama, 1854 Perry’s

troops landing in Yokohama, 1854

Shiryo Hensanjo, University of Tokyo

|

Some

of these artistic responses reflected bravado and an attempt to rally

domestic support against the foreign threat. In anticipation of Perry’s

arrival, the Shogun’s government had mobilized its own samurai

forces and ordered daimyo (local lords) throughout the land to send

troops to defend the capital. Thousands of armed warriors manned the

shoreline when Perry landed on his two visits. In the renderings of

the Narrative, these soldiers and officials appear calm and unruffled,

even when mounted on horseback or challenging the American crew that

was surveying Edo Bay. And while tension inevitably accompanied these

encounters, discipline and order did prevail. No violent incidents

occurred, and Japanese renderings of the first meetings of the two

sides also convey a sense of formality.

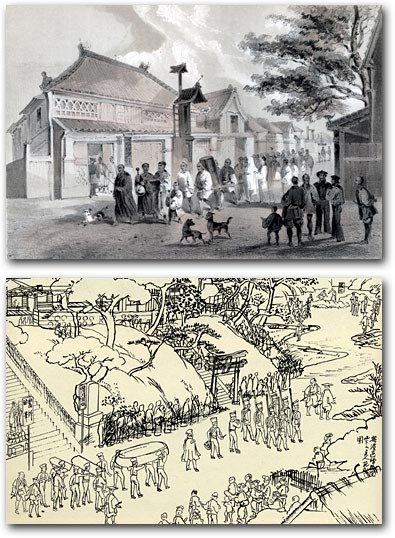

There were even unanticipated occasions where each side had the opportunity

to observe and record a common solemn moment on the part of the other—a

funeral, in this instance—and did so with differing styles,

to be sure, but also with a shared respectfulness. Thus a lithograph

in the Narrative depicting a Buddhist funeral procession in Shimoda

has an interesting counterpart in a Japanese sketch of the American

funeral procession for marine private Robert Williams, who died of

illness during Perry’s second visit. After brief and courteous

negotiation, the Japanese not only agreed to allow the deceased to

be buried on Japanese soil, but also had Buddhist priests participate

in the funeral service. The respect the Americans showed to the dead

clearly helped weaken the familiar stereotypes of “southern

barbarians” and “foreign devils.” At the same time,

the American tolerance of Buddhist participation in the rites of interment

offers a striking contrast to more invidious popular evocations of

the Japanese as “heathen.”

|

Japanese funeral in Shimoda, from the official

Narrative

Funeral procession of Private Williams,

by Tohohata (Osuke) 1854

Shiryo Hensanjo,

University of Tokyo |

|

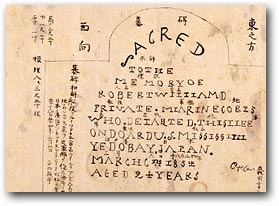

Inscription

from Robert Williams’s gravestone in the 1854 “Black Ship Scroll” Inscription

from Robert Williams’s gravestone in the 1854 “Black Ship Scroll”

Honolulu Academy of Art |

So

great was the impression left by the death of Williams that the

long “Black Ship Scroll” painted in Shimoda in 1854

included a drawing of the inscription on his tombstone.

In all, four Americans with the Perry mission died and were buried

in Japan. Private Williams, originally buried in Yokohama, was reinterred

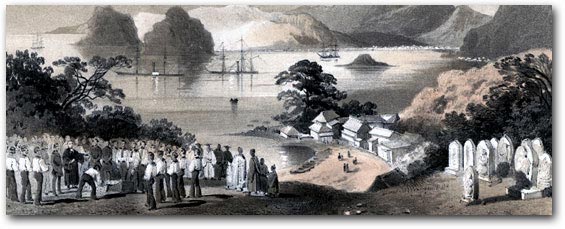

in Shimoda. One of Heine’s most evocative illustrations depicts

Americans and Japanese, including a Buddhist priest, in a hillside

cemetery in Shimoda, the American fleet visible at anchor in the

harbor.

|

|

Heine’s

1854 rendering of the harbor at Shimoda “from the Heine’s

1854 rendering of the harbor at Shimoda “from the

American Grave

Yard” (detail), from the official Narrative

|

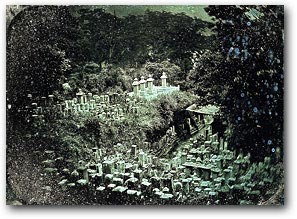

By

rare good fortune, we have a daguerreotype of the four American graves,

most likely taken the following year. Evocative in its own way, the

photograph also highlights the romanticism of Heine’s vision

of these historic encounters. By

rare good fortune, we have a daguerreotype of the four American graves,

most likely taken the following year. Evocative in its own way, the

photograph also highlights the romanticism of Heine’s vision

of these historic encounters.

|

|

Four

American gravestones in the cemetery of Gyokusenji

temple in Shimoda. Daguerreotype attributed to Edward Kern, ca. 1855 Four

American gravestones in the cemetery of Gyokusenji

temple in Shimoda. Daguerreotype attributed to Edward Kern, ca. 1855

George Eastman House

|

In

ways absent from the American graphics, however, Japanese artists

also succeeded in conveying a tense willingness to fight if need be

on the part of the Japanese defenders. Colored as well as black-and-white

prints depicted samurai crouched in readiness for imminent battle.

|

|

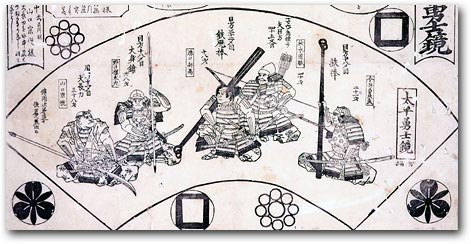

Samurai

guards at Edo Bay, detail from a kawaraban broadsheet, 1854 Samurai

guards at Edo Bay, detail from a kawaraban broadsheet, 1854

Ryosenji Treasure Museum |

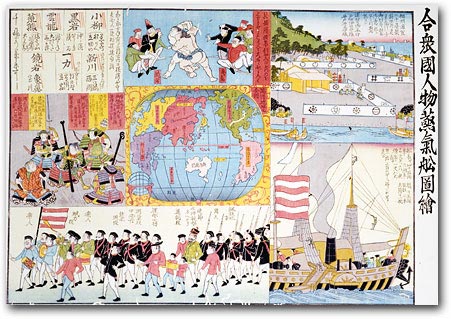

Detail

from a montage titled “Pictorial Depiction of American People and Steamship” Detail

from a montage titled “Pictorial Depiction of American People and Steamship”

ca. 1854

Ryosenji Treasure Museum |

|

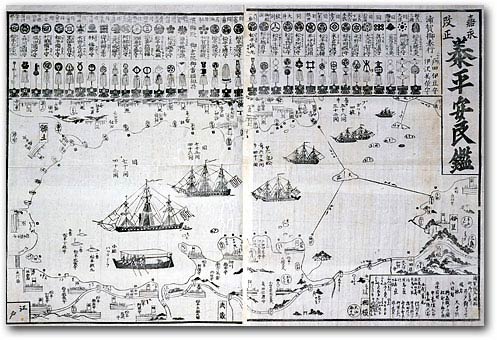

In some cases, the massive mobilization of samurai was conveyed in a

traditional “heraldic” manner. Here, depiction of the

foreign fleet sitting offshore was paired with a row of tiny drawings

of the distinctive crests, decorated staffs, and other insignia that

identified different daimyo and their retainers.

|

|

Japanese

deployment against U.S. black ships at Edo Bay, 1854 kawaraban Japanese

deployment against U.S. black ships at Edo Bay, 1854 kawaraban

Ryosenji Treasure Museum

|

Even

decades later, after Japan’s new leaders had dismantled the

feudal system and embarked on a policy of ardent “Westernization,”

the image of heroic warriors bristling to take on Perry’s imperialist

intruders had an avid audience. The most flamboyant woodblock print

of the imagined samurai defenders in Edo Bay, for example, dates from

1889 and conveys a sense of both peril and gritty determination that

could still rouse the fervor of new nationalists in a new nation.

|

|

Samurai

from various fiefs mobilize to defend the homeland against Perry’s

intrusion, Samurai

from various fiefs mobilize to defend the homeland against Perry’s

intrusion,

1889 woodblock print by Toshu Shogetsu

Shiryo Hensanjo, University of Tokyo

|

The

most audaciously fictional rendering of Perry and the Japanese was

circulated as a kawaraban broadsheet around 1854. This depicts

the commodore prostrating himself before an official in full samurai

armor seated on the traditional camp stool of a fighting general.

|

Perry

prostrating himself before a samurai official, kawaraban

(detail) ca. 1854

Ryosenji Treasure Museum

|

|

Widely

known for his haughty demeanor even before the Japan expedition, Perry

took extraordinary care never to display the slightest sign of subordination

or obsequiousness in his dealings with Japanese officials. Had he

seen this little pearl of propaganda, it surely would have made his

hair curl.

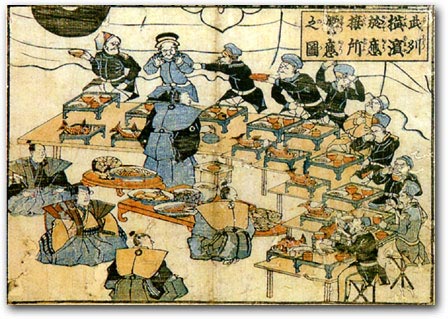

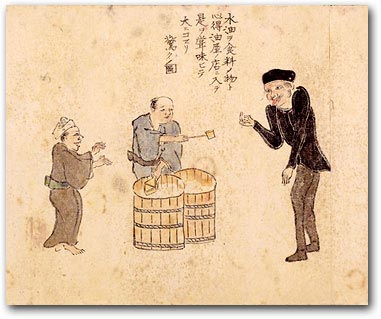

More than a few Japanese graphics had a cartoon quality, and some

were deliberately humorous—again, something never seen in the

sober American illustrations. One of the liveliest episodes that took

place during the second visit, for example, was a banquet on the Powhatan.

As it happens, we know from various sources that this evolved into

less than formal behavior. In an entertaining letter to his wife,

one of Perry’s officers (Lieutenant George Henry Preble) recounted

that, “in accordance with the old adage that if they eat hearty

they give us a good name,” he and his comrades took care to

keep the plates and glasses of their guests full. “Doing my

duty therefore, in obedience to orders,” he continued, “I

plied the Japanese in my neighborhood well, and when clean work had

been made of champagne, Madeira, cherry cordial, punch and whisky

I resorted to the castors and gave them a mixture of catsup and vinegar

which they seemed to relish with equal gusto.” Both sides interspersed

their libations with friendly toasts.

|

|

Banquet

on board the Powhatan Banquet

on board the Powhatan

|

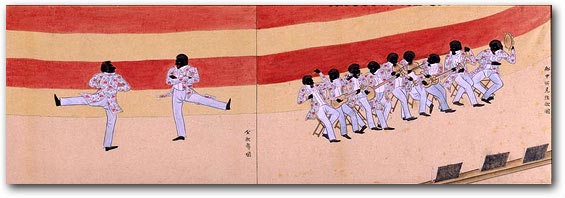

The

band played, and American officers danced with Japanese officials

in formal robes. One of the commissioners was so carried away by the

end of the evening that he threw his arms around Perry’s neck,

embraced him rather sloppily, crushed his epaulettes, and (in a subsequently

often-quoted phrase) burbled “Nippon and America, all the same

heart.” As Preble recounted the story, when asked how he could

tolerate such behavior, the commodore replied, “Oh, if he will

only sign the Treaty he may kiss me.” Gunboat diplomacy was

a demanding business.

One could never imagine any of this from Heine’s entirely decorous

rendering of the event in the official Narrative, and unfortunately no irreverent Japanese artists

were present to record the scene.

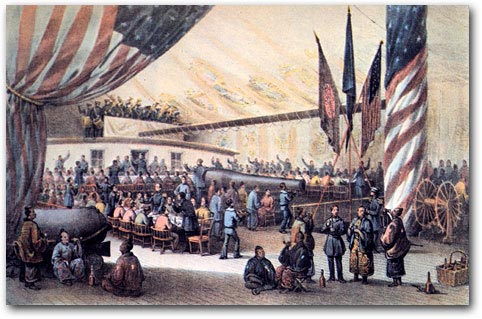

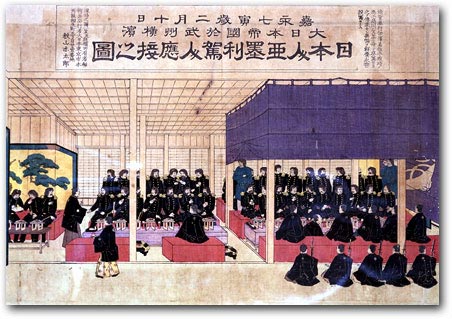

When the Japanese reciprocated with a banquet of their own, on the

other hand, we have not only a somber rendering of this (sketched

at the time but published as a woodblock print many years later),

but also an anonymous and quite disorderly print that suggests the

Westerners, although not required to sit Japanese style on the floor,

clearly had a difficult time swallowing the native cuisine.

|

|

Japanese

reception for the Americans, late-19th-century woodblock print from

a sketch done at the time

Ryosenji Treasure Museum |

“Entertainment Held in the Reception Hall at Yokohama”

(detail), ca. 1854

Peabody Essex Museum |

|

Frequently,

Japanese artists resorted to montage to convey a sense of the multifaceted

nature of the Perry encounter. The landing at Yokohama in March 1854,

for example, inspired a number of prints combining views of the black

ships at anchor with drawings of the commodore and his crew marching

in parade.

One elaborate montage, titled “Pictorial Depiction of American

People and Steamship,” featured a map of the world in the center

(with Japan in the center of the map), surrounded by depictions of

the curtained-off Japanese shore defenses, a gunboat belching smoke,

Perry and his attendants in rather untidy parade (the Americans had

better posture when their own artists drew them), the samurai in full

armor we already have seen, and crewmen from the black ships gaping

at the sight of two giant sumo wrestlers.

|

“Pictorial

Depiction of American People and Steamship”

ca. 1854

Ryosenji Treasure Museum |

|

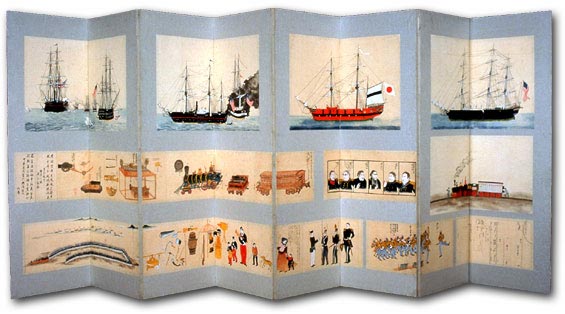

The

most spectacular assemblage of graphics, completed at a later date,

took the form of a dramatic eight-panel standing screen, now known as the “Assembled

Pictures of Commodore Perry’s Visit.” On this were affixed

depictions of the black ships, Perry and other members of his mission

(including ordinary crew), troops in formation, entertainments, artifacts

the Americans brought with them, and the official gifts they proffered

(including a telegraph apparatus and a small model train).

|

|

“Assembled

Pictures of Commodore Perry’s Visit” “Assembled

Pictures of Commodore Perry’s Visit”

eight-panel folding screen

Shiryo Hensanjo, University of Tokyo

|

|

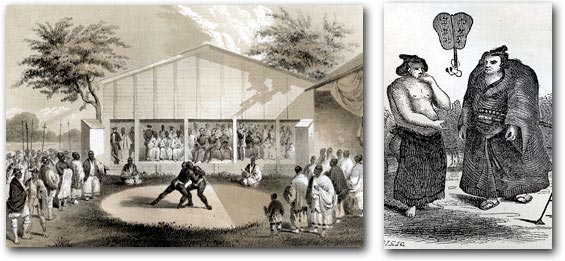

Sumo,

as it turned out, attracted artists on both sides. The Narrative featured

a lithograph (by W. T. Peters) of an outdoor sumo match observed by

a crowd of Japanese and Americans including Perry himself, as well

as a pencil drawing of two sumo champions by the always respectful

Heine.

The sumo wrestlers did not impress everyone favorably, however. The

Narrative described them as “over-fed monsters” and found

the wrestling matches themselves “disgusting”—a

mere “show of brute animal force.” In his personal journal,

Perry dismissed the bouts as a “farce” and referred to

the eventual winner as “the reputed bully of the capital, who

seemed to labor like a Chinese junk in chow-chow water.” The

sight of some twenty-five or thirty of these brawny men grouped together

struck him as “giving a better idea of an equal number of stall-fed

bulls than human beings.”

|

|

Sumo detail from

1854 montage

Ryosenji Treasure

Museum |

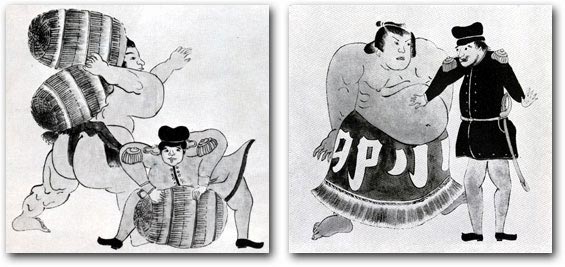

By

contrast, in Japanese eyes these same figures became an almost irresistible

vehicle through which to intimate Japan’s formidable strength,

against which the foreigners were puny and powerless. In the “Pictorial

Depiction of American People and Steamship” montage, the American

spectators appear small, ludicrous, and astonished at the sight of

two of these giants grappling with each other.

In the same spirit, the spectacle of these strongmen hefting huge

bales of rice the Americans were unable to budge (they weighed over

125 pounds) became another witty way of suggesting that the intruders

were no match for Japanese. A scroll of first-hand sketches of the

foreigners prepared by a retainer of the daimyo of Ogasawara included

skillful line drawings of awed marines examining the bulk of a sumo

champion.

Even Perry was given the opportunity to feel the muscles of one of

these giants. The artists naturally portrayed him as duly impressed,

although the official report tells us he was merely expressing surprise

“at this wondrous exhibition of animal development.”

|

|

|

Sumo

wrestlers carry rice bales, 1854 (above, left)

Collection of DeWolf Perry

Perry and a Japanese wrestler, 1854 (above, right)

Collection of DeWolf Perry

Marines examining a sumo

wrestler, 1854 (left)

Smithsonian Institution |

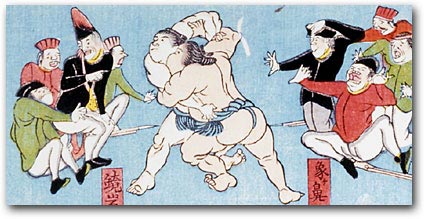

In

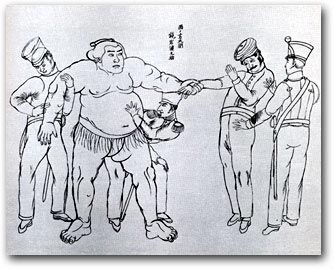

the decade following the Perry expedition, the larger-than-life sumo

wrestler continued to provide a small vehicle for iconographic bravado.

After a new commercial treaty was signed in 1858 and foreigners began

to flood into the country, woodblock artists portrayed these native

heroes tossing around, not bales of rice, but the hairy barbarians

themselves.

|

“The

Glory of Sumo Wrestlers at Yokohama,” “The

Glory of Sumo Wrestlers at Yokohama,”

1860 and 1861

Ryosenji Treasure Museum |

|

When

it came to promoting human curiosities, however, Perry was not to

be outdone. The American counterpart to the sumo wrestler was white

men in black-face, as well as flesh-and-blood Negroes.

|

|

Minstrel

show on Minstrel

show on

the Powhatan

Chrysler Museum of Art (above)

Shiryo Hensanjo,

University of Tokyo (right) |

|

|

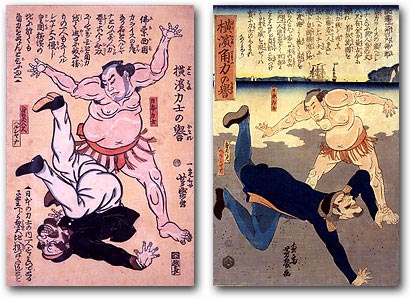

In

Japan (as well as elsewhere on the voyage to and from Japan), Perry’s

favorite entertainment was an “Ethiopian concert” featuring

white men playing the roles of “Colored ‘Gemmen’

of the North” and “Plantation ‘Niggas’ of

the South,” and singing such songs as “Darkies Serenade”

and “Oh! Mr. Coon.” Although the Narrative dwells on the

“delight to the natives” these performances gave, it remained

for Japanese artists to preserve them for posterity.

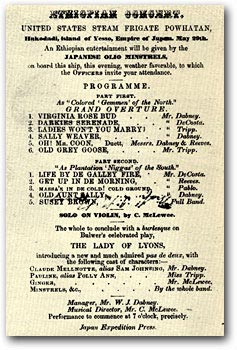

“Ethiopian Concert”

program from minstrel show

on the Powhatan |

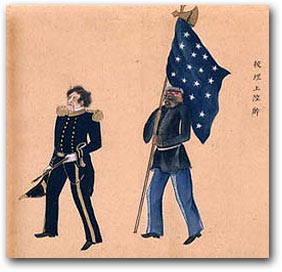

From

the moment he first stepped on Japanese soil in 1853 to present the

letter from President Fillmore, Perry also sought to impress the Japanese

with authentic black men. “On either side of the Commodore,”

the Narrative tells us,

Perry,

accompanied by a “tall,

well-formed negro,” delivering

President Fillmore’s letter,

1853 Perry,

accompanied by a “tall,

well-formed negro,” delivering

President Fillmore’s letter,

1853

Chrysler Museum of Art |

“marched a tall, well-formed negro,

who, armed to the teeth, acted as his personal guard. These blacks,

selected for the occasion, were two of the best-looking fellows of

their color that the squadron could furnish.” Here again, it

is the Japanese side that has left a graphic impression of these stalwart

aides.

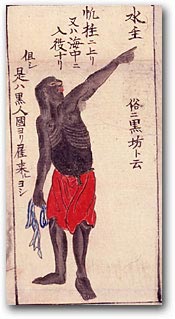

In other Japanese renderings, however, blacks who accompanied the

mission were less than handsome and well-formed. When Perry and his

men visited the two treaty ports designated by the Treaty of Kanagawa,

artists in both Shimoda and Hakodate drew unflattering portraits of

black crewmen who came ashore. They would never be confused with the

stalwart standard bearers who flanked Perry when he presented the

president’s letter.

|

|

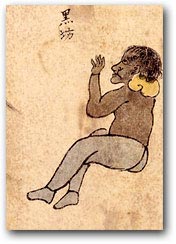

Crewman “hired from

a country of black people,”

from the watercolor

“Black Ship and Crew”

ca. 1854

Ryosenji Treasure Museum |

|

“Black man” from

the “Black Ship Scroll”

1854

Honolulu Academy of Art |

|

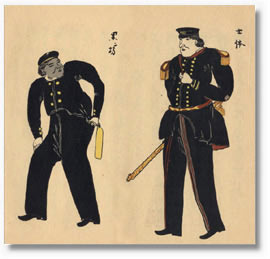

Two

images of Perry and black crew members in

Hakodate

Hakodate Kyodo Bunkakai

|

|

At

the time Perry was engaged in opening Japan to “civilization,”

slavery was still widespread in the United States and minstrel shows

were an enormously popular form of entertainment. (The Narrative dwells

at some length on their appealing combination of “grotesque

humor and comic yet sentimental melody.”) The Japanese, whose

prior contact with dark-skinned peoples was negligible, responded

to these encounters with undisguised curiosity. As filtered through

the eyes of popular artists, however, this interest emerges more as

bemusement about the human species in general than any clear-cut prejudice

toward foreigners, or toward blacks in particular.

This seems, at first glance, an unlikely response from a racially

homogeneous society that had lived in isolation for so long. It was,

however, a logical response when seen from the perspective of the

mass-oriented popular culture of late-feudal Japan. Whereas Heine

and his colleagues exemplified restrained “high art” traditions

of representation, Japanese artists catering to a popular audience

had long engaged in exaggeration and caricature. Their purpose was

to entertain, and in the tradition of woodblock prints in particular,

every conceivable type of subject, activity, and physical appearance

was deemed suitable for representation—whether it be scenery,

the “floating world” of actors and courtesans, mayhem

and grotesquerie, or outright pornography. This protean fascination

with the human comedy carried over to artistic renderings of the various

types of foreign individuals who came ashore with the commodore in

1853 and 1854.

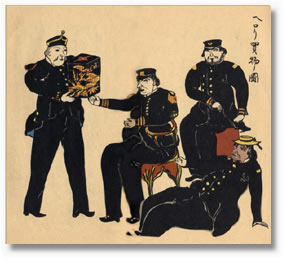

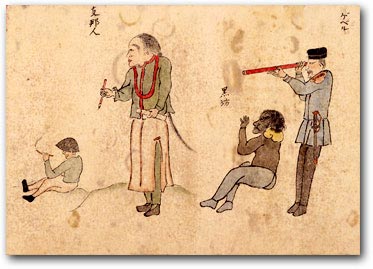

It is in this spirit that the bare-chested black sailor in Shimoda

was introduced as but one of many characters in a popular scroll that

treated virtually all members of the expedition as rather odd but

essentially entertaining. The larger scene in which he appears includes

two “Chinese” who accompanied the expedition, as well

as a white man with a telescope.

|

|

Chinese members of

the Perry expedition with

black crewman and white

man with a telescope

“Black Ship Scroll” (detail)

Honolulu Academy of Art

|

|

|

This

version of the “Black Ship Scroll” (beginning section

shown here) This

version of the “Black Ship Scroll” (beginning section

shown here)

is approximately 30-feet long and is read from right to left.

|

|

|

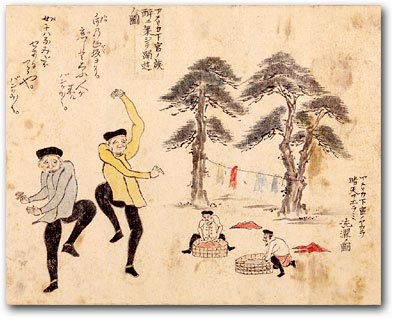

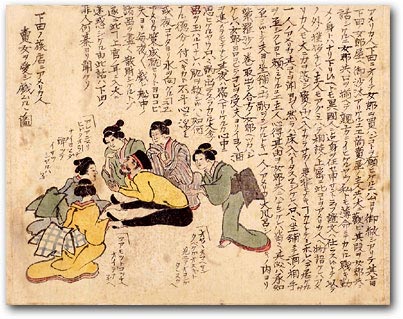

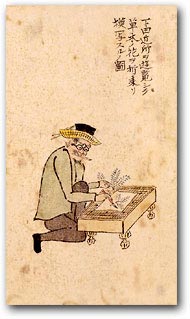

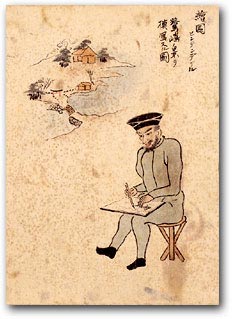

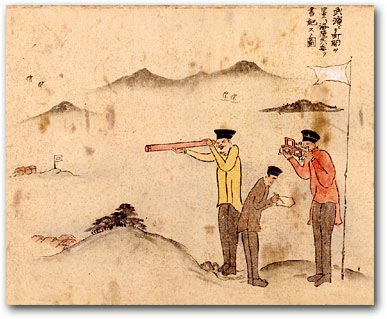

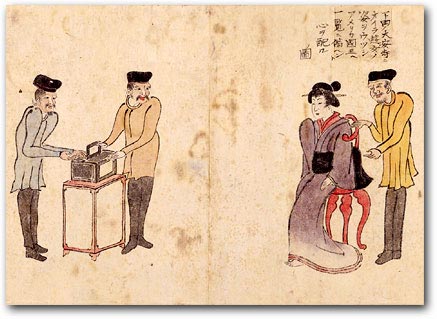

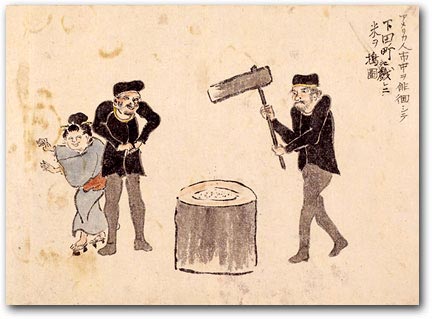

This

“Black Ship Scroll” (which came to exist in several variant

copies) also featured witty renderings of crewmen engaged in activities that Perry’s artists

never dreamed of recording: inebriated sailors dancing, for example,

and a seaman surrounded by prostitutes. In a nice representation of

foreigners making their representations, the Shimoda scrolls also

included such scenes as Heine making sketches, Dr. Morrow collecting

and recording his specimens of plants, foreigners surveying the countryside,

and three aroused Americans (the tongue of one is protruding) making

a daguerreotype of a courtesan to present to the “American king.”

|

|

Inebriated American

crewmen dance,

while others

do their laundry |

An American sailor

ingratiating himself with prostitutes in Shimoda (together with a

long and amusing account of how he succeeded in doing so) |

|

However

exaggerated such renderings may have been, they conveyed a playfulness

and vitality fully in keeping with the practices of Japanese popular

art—and conspicuously different from the high-minded “realism”

of Heine and company. From this perspective, the great cultural encounter

was genuinely amusing.

|

|

|

Botanist James Morrow and artist William Heine |

Surveying the

Shimoda countryside |

|

|

Eliphalet Brown, Jr.

and assistants

making a

daguerreotype of

a courtesan |

A bemused Japanese woman watches American sailors attempting to hull

rice |

|

|

An American crewman

grimaces after tasting

hair oil he mistook for

an edible delicacy |

|

|

A variant version

of the “Black Ship Scroll”

A variant version

of the “Black Ship Scroll”

|

|

|