| |

Encounters: Facing “East”

|

|

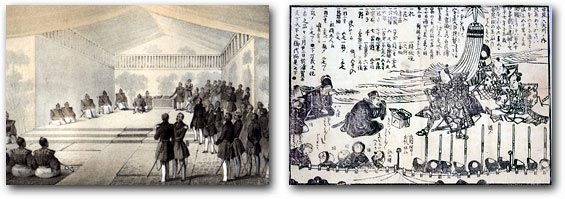

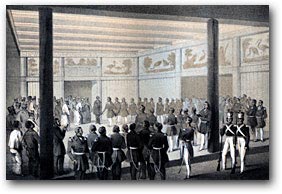

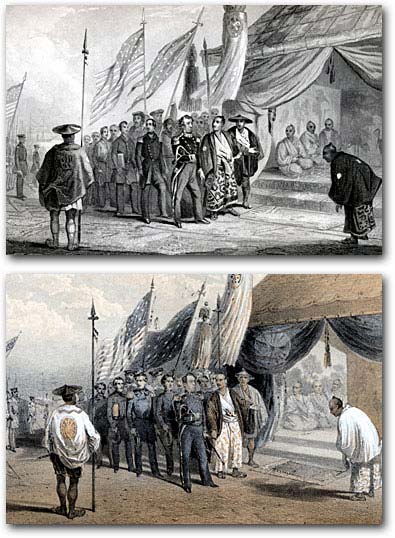

“Delivery of the President's Letter” “Delivery of the President's Letter” |

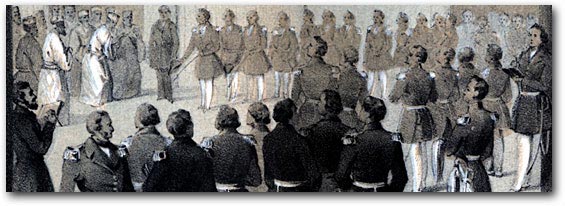

“Perry Taking a Bow” “Perry Taking a Bow” |

|

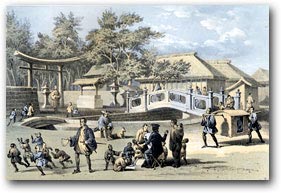

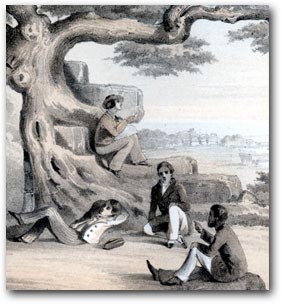

Detail,

from the official Narrative Detail,

from the official Narrative |

Ryosenji

Treasure Museum |

By far the greatest single source of American illustrations of the

Perry expedition is to be found in volume one of the three-volume

official Narrative published between 1856 and 1858. The most numerous

and accomplished

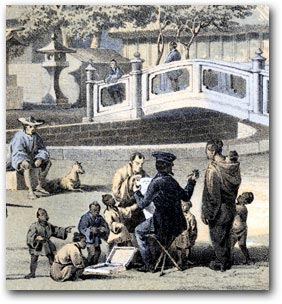

Heine sketching in the Ryukyu Islands,

1853, from the official Narrative |

of these illustrations were done by William Heine,

a German-born artist who was only 25 years old when he first

accompanied Perry to Japan.

Heine, who worked primarily with sketchpad and watercolors, brought a gentle,

panoramic, romantic realism to both the selection and execution of

his subjects. His landscapes were invariably scenic. Where people

were concerned, he preferred them in substantial numbers. He rarely

lingered on the “exotic,” did not dwell much (as happened

later) on various social “types,” did not seek out the

sensational. So enraptured was Heine by the opportunity to immerse

himself in new landscapes and cultures that, now and then, he even

painted himself painting the scene being depicted.

|

|

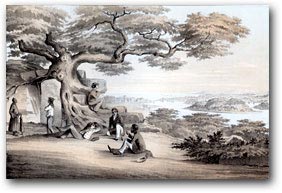

Shui

Castle, Ryukyu Islands, Shui

Castle, Ryukyu Islands,

with two artists sketching the scene,

from the official Narrative

(detail below) |

|

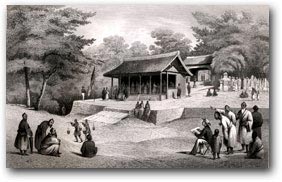

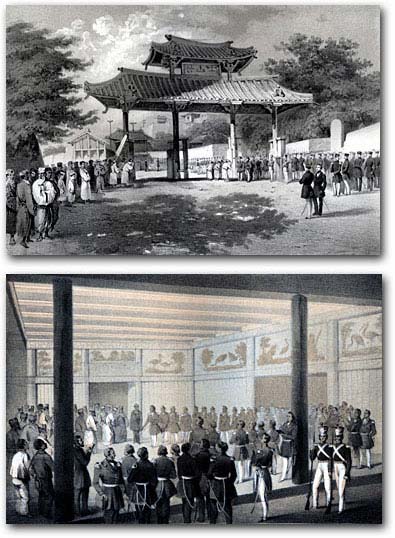

Entrance to Shinto shrine in Shimoda,

from the official Narrative (detail below)

|

“Temples” attracted Heine (he, or whoever captioned

the reproductions of his artwork, made no distinction between Buddhist

temples and Shinto shrines), but he depicted them with the same appreciative

regard that he brought to trees, mountains, skies, crowds, individuals,

and other natural and human phenomena. He turned his brush (and also

his drawing pencil) to a few religious statues and monuments, but

again with restraint and respect—a striking contrast to the

more garish renderings of imagined heathen deities that had appeared

in Western publications prior to Perry’s arrival.

Since the Perry expedition never visited Edo or any other huge urban

center, the illustrations in the official report conveyed the impression

of a placid, rustic land of quiet villages and modest towns.

|

Heine and his colleagues gave only passing attention to commercial

activities, and only rarely entered behind closed doors. With but

one exception, they chose not to illustrate subjects that provoked

moral indignation among some members of the mission (and delighted

more than a few crewmen), such as prostitution, pornography, and public

baths.

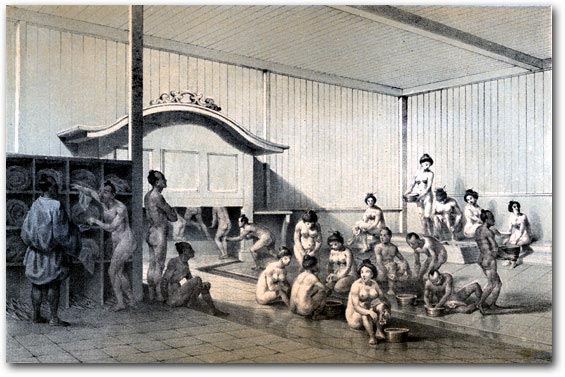

The only illustration in the Narrative that subsequently provoked

shock and condemnation among Americans depicted a public bathhouse

in Shimoda. Men, women, and children bathed together in these establishments,

and good Christians found them appalling. Dr. James Morrow, the mission’s

botanist, denounced the bath in Shimoda as one more example “of

the licentiousness and degradation of these cultivated heathen,”

for example, while a ship’s clerk sourly observed that “their

religion might encourage cleanliness,” but it did so in a “repulsive

and indecent manner.” The official report itself recorded that

“a scene at the public baths, where the sexes mingle indiscriminately,

unconscious of their nudity, was not calculated to impress the Americans

with a very favorable opinion of the morals of the inhabitants.”

|

Heine

and shipmates exploring the Ryukyu countryside, from the official Narrative (detail below) Heine

and shipmates exploring the Ryukyu countryside, from the official Narrative (detail below)

|

|

Heine’s

controversial rendering of a public bath in Shimoda Heine’s

controversial rendering of a public bath in Shimoda |

Heine’s

illustration of the bathhouse in Shimoda was removed from later editions

of the Narrative. Where intercultural relations are concerned, morality

obviously was a two-way mirror in this case. For the manner in which

the Americans pointed to mixed bathing as evidence of Japanese lewdness

and wantonness was strikingly similar to John Manjiro’s response,

only a few years earlier, to the shocking spectacle of American men

and women kissing in public.

The original artwork by Heine and his colleagues was seen by very

few individuals. Rather, it reached the public in several different

forms. Some 34,000 copies of the official three-volume Narrative were

published (at the substantial cost of $400,000), of which over half

were given to high government officials, members of Congress, and

the Navy Department.

Chapter

heading drawing

from the official Narrative |

The first and most pertinent volume of the set included some 165 handsome

woodcuts and tipped-in lithographs depicting not only Japan but other

stops on the two voyages—including China, the Bonin islands,

and, of greatest interest, Okinawa in the Ryukyu (“Lew Chew”)

islands.

In

addition, this first volume also featured many small reproductions

of pencil drawings by Heine, particularly at the beginnings and ends

of chapters. Mid-century Western voyagers, artists, and scientists

were intent on “mapping” literally all aspects of the

little-known world, and in volume two several-score brilliantly colored

plates were devoted to natural life, particularly fishes and birds.

(Additional plates depicting the plants of Japan failed to be published

due to vanity and obstreperousness on the part of Dr. Morrow, who

collected and drew illustrations of hundreds of specimens, but held

these back in the hopes of seeing a separate publication devoted solely

to his own findings. This failed to materialize, and his work has

been lost.) The third volume of the Narrative, of little interest

today, reproduced charts of the stars recorded over the course of

the two long voyages.

|

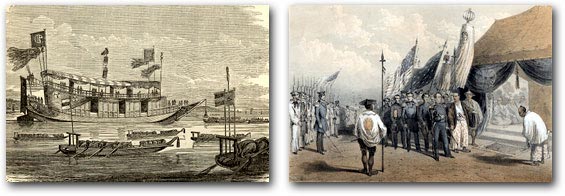

The

official publication was expensive, however, and the general public

only encountered this handsome visual record indirectly. An affordable

trade edition of volume one was published in 1856, with fewer lithographs

and color throughout reduced to black and white. At the same time,

a small number of illustrations (including some that did not appear

in the official or commercial publications) were reproduced as large

brightly colored “elephant” lithographs. One could thus

encounter "Perry’s Japan" in various tones and formats.

|

|

Illustration

from the 1856

commercial edition |

Tinted

lithograph from the Tinted

lithograph from the

official printing of 1856 |

Independent

large-format

lithograph, ca. 1855–56

|

|

It also happened that, in moving from one form of printing to another,

the details of the original rendering were slightly altered—as

seen, for

example, in the famous depiction of Perry’s landing in Yokohama

that appears in the official and trade editions.

Two versions of

Commodore Perry meeting

officials at Yokohama

The trade edition of the

Narrative (detail, above left)

The official government

edition (detail, left)

|

|

| From the 1853 Expedition |

|

The

artwork in the Narrative (and independent lithographs) begins with

impressions of ports of call en route to Japan (including scenes from

Ceylon, Singapore, Canton, and Hong Kong), and then presents a record

of major interactions between Perry and officials in “Lew Chew”

and Japan.

|

|

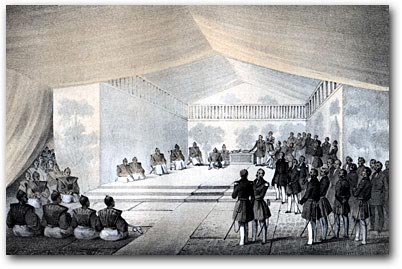

On the first visit to Okinawa, we move from the “exploring party”

mingling with native peoples in bucolic settings to the castle in

Naha, where Perry and his entourage paused by the imposing “Gate

of Courtesy” and then attended a crowded formal reception.

Gate of Courtesy

at the castle in Okinawa

(above, left)

Reception at Shui Castle, Okinawa (left)

|

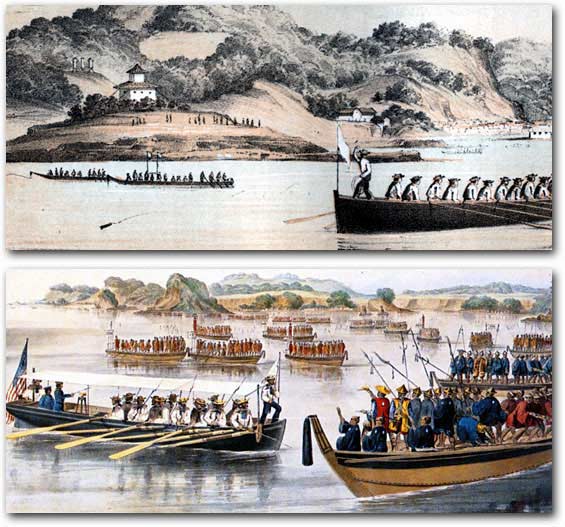

Moving

on to Edo Bay, the artists recorded a tense moment when the Americans

began to survey the harbor and were briefly challenged by Japanese in small

boats—a dramatic confrontation, referred to as “Passing the Rubicon,” that was

inexplicably only made available as an independent print.

|

|

The White House Collection

|

The

Americans sounding and surveying Edo Bay (detail, top, from the official Narrative)

“Passing

the Rubicon”: Japanese officials confront the surveying party (detail, bottom)

|

Thereafter,

all becomes decorous again. From the brief 1853 mission come iconic

paintings of Perry coming ashore in Japan for the first time (on July

14, at Kurihama) and delivering President Fillmore’s letter

requesting the end of the policy of seclusion.

|

|

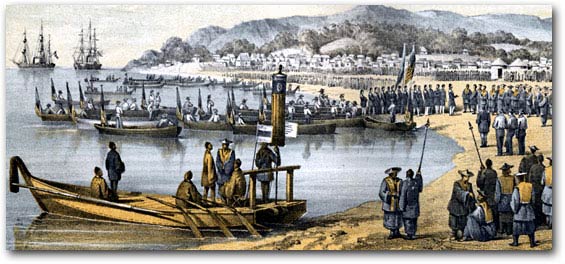

The

landing at Kurihama The

landing at Kurihama

(detail)

Delivery of President

Fillmore’s letter

|

|

|

| From the 1854 Expedition |

|

The

commodore’s return visit in 1854, which lasted for several months

and saw the opening of Shimoda and Hakodate to foreign vessels, provided

the occasion for more extended artwork. Perry’s landing in Yokohama on March 8 inspired a crowded scene

of troops on parade before a horizon prickled with the masts of the

black ships, as well as a solemn rendering of the commodore greeting

the Japanese commissioners.

|

|

The

landing at Yokohama (detail) The

landing at Yokohama (detail)

Yokohama Archives of History

|

|

| “Imperial

barge” at Yokohama |

Japanese

officials greet Perry at Yokohama

|

|

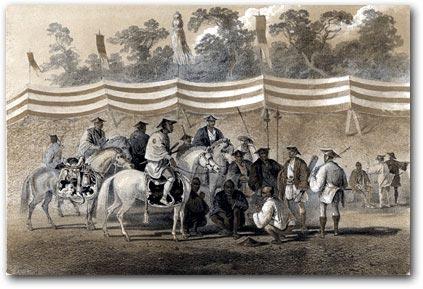

In

another illustration, armed samurai were depicted clustered together,

some mounted and some on foot (a rare close-up of the thousands of

warriors mobilized

for defense).

Samurai

defense forces

(detail) |

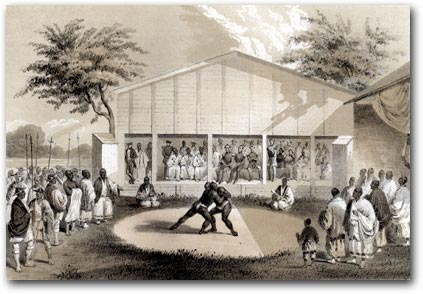

Formal

occasions— the presentation of American gifts, a banquet on

Perry’s flagship, a performance of sumo wrestling—were

duly recorded.

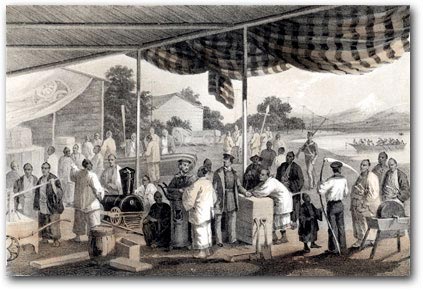

Delivery

of the Delivery

of the

American presents

at Yokohama |

|

|

|

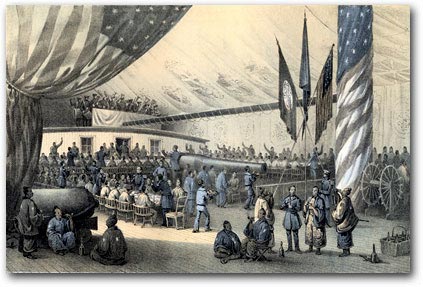

Banquet on board

the Powhatan |

Sumo wrestler

at Yokohama |

|

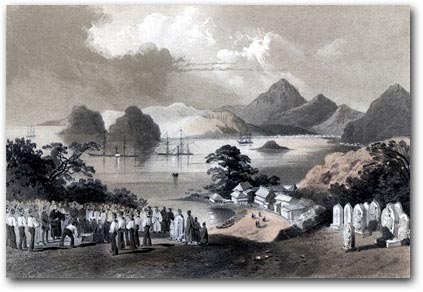

Yokohama,

and subsequently the newly designated “treaty ports” of

Shimoda and Hakodate, provided the Americans with more intimate access to the countryside

and the ordinary people who lived there.

The rugged vistas in these areas inspired Heine to new heights of

scenic romanticism, and he and his fellow artists also took advantage

of their excursions onshore to depict the local people and their places

of worship and daily activities (including the scandalous public bath

in Shimoda). Although these detailed scenes are usually crowded with

people, often with foreigners and natives intermingling, there is

little sense of tension or strangeness. The atmosphere is serene.

Everyone, native and foreigner alike, is comely. In the American record,

these first encounters come across as almost dream-like.

|

|

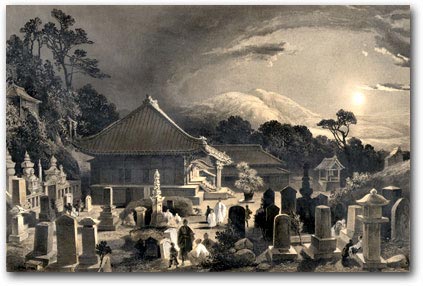

Shimoda “from the

American Grave Yard” |

Moonlit graveyard at Ryosenji Temple, Shimoda

Harvard University

Library |

|

|

| A Gallery of Images

from the Expedition |

|

|

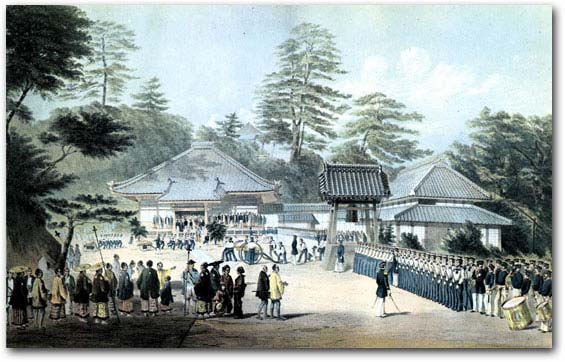

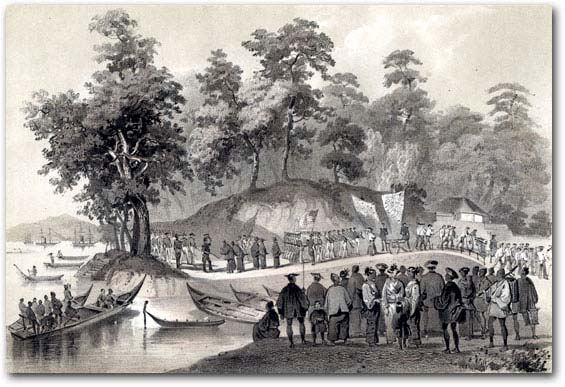

Perry’s

troops in formation at Ryosenji Temple, Shimoda Perry’s

troops in formation at Ryosenji Temple, Shimoda

US Naval Academy Museum

|

|

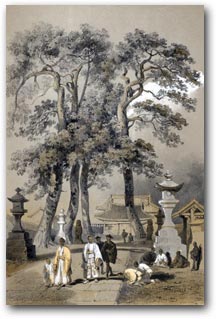

Hachiman

shrine, Hachiman

shrine,

Shimoda |

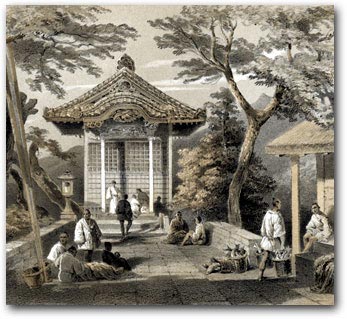

Mariner’s

temple, Mariner’s

temple,

Shimoda (detail)

|

|

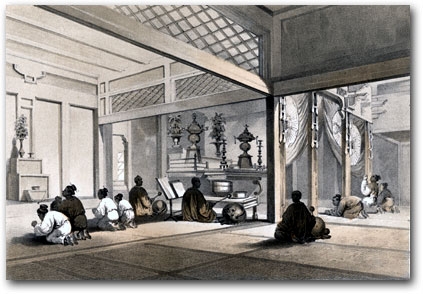

Devotions in a

Buddhist temple,

Shimoda |

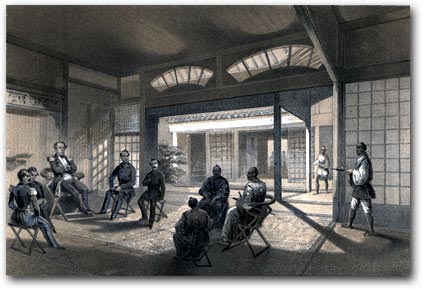

Perry conferring

with local officials

in Hakodate |

|

|

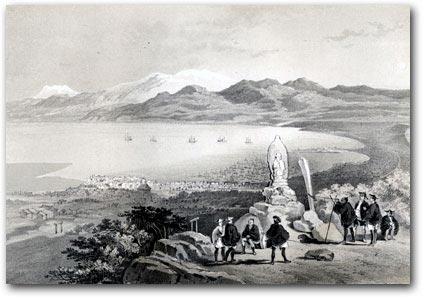

Hakodate

“from Telegraph Hill” |

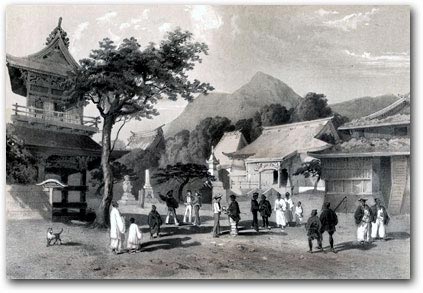

Street by a temple

in Hakodate |

|

|

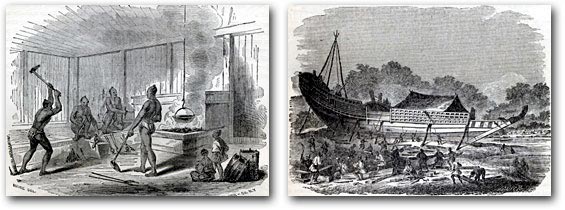

Blacksmith

shop Blacksmith

shop |

Shipyard Shipyard

|

|

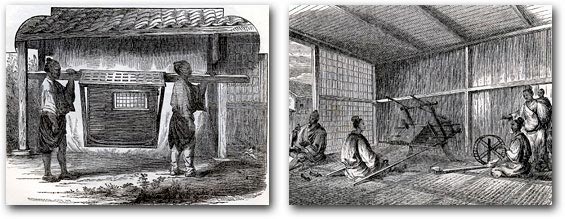

Japanese

kago (palanquin) Japanese

kago (palanquin) |

Spinning

and weaving Spinning

and weaving

|

|

Commodore

Perry bids farewell to officials in Shimoda Commodore

Perry bids farewell to officials in Shimoda

|

|

|