| |

|

Perry,

1854 Perry,

1854 |

Perry, 1852 |

|

Ryosenji

Treasure Museum Ryosenji

Treasure Museum |

Library of Congress |

Westerners

following Perry’s exploits from afar relied on photographs,

or far more commonly lithographs or woodcuts based on photographs,

to imagine what the commodore looked like. Around the time of the

Japan voyages, we encounter him in several renderings: sour in civilian

garb just before departing, for example, and posing in profile for

a photo used in casting a commemorative coin soon after he had returned.

|

|

Daguerreotype

of Perry

1852

Library of Congress

|

Silver

coin with Perry’s profile, 1855

and the daguerreotype on which it was based

US Naval Academy Museum

|

The

most famous portrait, taken by the great photographer Mathew Brady

after the completion of the Perry mission, portrays the commodore

standing in full uniform.

In popular illustrated periodicals, where photographs were reprocessed as lithographs and the like, his features became somewhat softened.

|

|

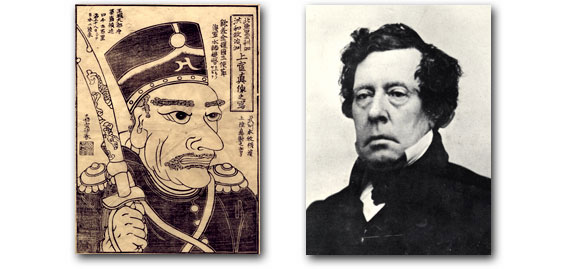

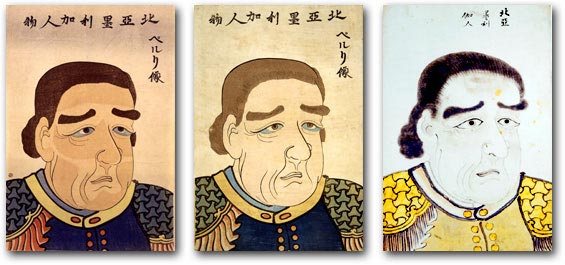

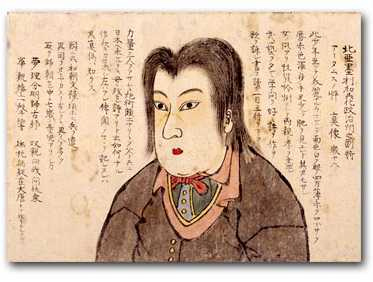

“Portrait of Perry,

a North American,”

woodblock print,

ca. 1854 (left)

Nagasaki Prefecture

Daguerreotype by

Mathew Brady (detail)

ca.1856

Library of Congress

|

As

sometimes happened with especially popular woodblock prints, this

rendering of “Portrait of Perry, a North American” actually

circulated in several versions, with subtle variations in detail and

coloring. In some versions, the commodore’s hair is reddish—clearly

evoking the familiar depiction of the Dutch as “red hairs.”

And in some, the whites of Perry’s eyes are blue.

|

|

Nagasaki

Prefecture Nagasaki

Prefecture

|

Peabody Essex Museum

|

Ryosenji

Treasure Museum Ryosenji

Treasure Museum

|

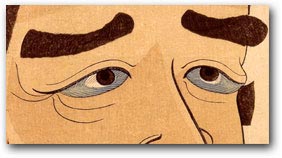

We

can offer both a simple and a more subtle explanation for these somewhat

startling eyeballs. In the popular parlance of feudal Japan, Westerners

were sometimes referred to as “blue-eyed barbarians,”

and it is possible that some artists were a bit confused concerning

where such blueness resided. That is the simple possibility. It was

also the case, however, that in colored woodblock prints in general—which

only emerged as a popular genre during the era of seclusion—ferocious

and threatening figures such as monsters and renegades were frequently

stigmatized by the same strange blue eyeball. Whatever the explanation,

popular renderings of Perry and his fellow “barbarians”

drew on conventions entrenched in the indigenous culture. We

can offer both a simple and a more subtle explanation for these somewhat

startling eyeballs. In the popular parlance of feudal Japan, Westerners

were sometimes referred to as “blue-eyed barbarians,”

and it is possible that some artists were a bit confused concerning

where such blueness resided. That is the simple possibility. It was

also the case, however, that in colored woodblock prints in general—which

only emerged as a popular genre during the era of seclusion—ferocious

and threatening figures such as monsters and renegades were frequently

stigmatized by the same strange blue eyeball. Whatever the explanation,

popular renderings of Perry and his fellow “barbarians”

drew on conventions entrenched in the indigenous culture.

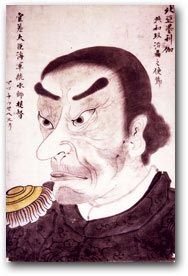

Perry

as a long-nosed tengu Perry

as a long-nosed tengu

or goblin ca. 1854

Ryosenji

Treasure Museum Ryosenji

Treasure Museum

|

Although

commercial artists immediately rowed out in small boats to draw pictures

of Perry’s fleet on the occasion of the first visit in July

1853, then and even thereafter few actually had the opportunity to

behold the commodore in person. This was due, in no little part, to

Perry’s decision to enhance his authority by making himself

as inaccessible as possible. Indeed, he remained so secluded prior

to the formal presentation of the president’s letter that some

Japanese, it is said, took to calling his cabin on the flagship “The

Abode of the High and Mighty Mysteriousness.”

Failing to see Perry personally left many artists with little but

their imaginations to rely on in depicting His High and Mighty Mysteriousness,

a situation that the majority of them serenely accepted and even

relished. And, in more than a few cases, they leave us with little

guesswork concerning where (beyond “red hairs” and “blue-eyed

barbarians”) their stereotypes were coming from. In one instance,

for example, we find the commodore presented as “Tengu Perry”—alluding

to the large, long-nosed goblin figures that folklore portrayed

as possessing uncanny powers.

|

|

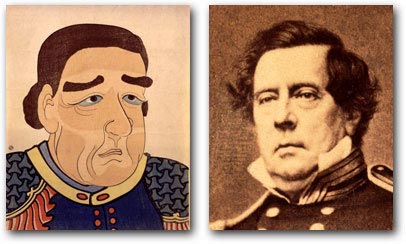

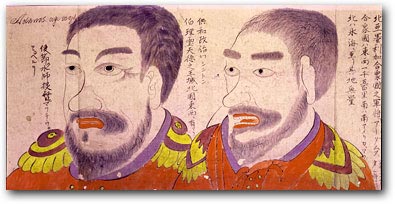

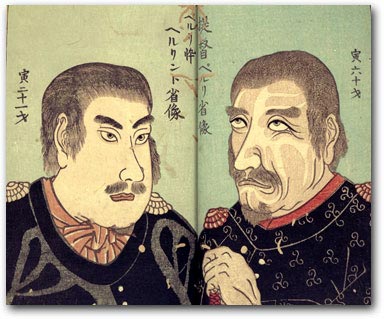

More common were prints and paintings that rendered Perry and his

fellow Americans conspicuously hirsute. In several such portraits,

we find him paired with Commander Henry A. Adams, his second-in-command.

Adams (left) and Perry

Ryosenji Treasure Museum |

Perry (left) and Adams,

from "The Pictorial Scroll

of the Arrival at Kurihama"

ca. 1854

Ryosenji Treasure Museum |

|

|

In another print, Perry is paired with his young son (named after

Perry’s famous brother Oliver), who accompanied him to Japan—here

sporting a trim mustache like his father, but lacking his father’s

goatee.

Perry and son,

woodblock print

1854

Ryosenji Treasure Museum

|

A

painting of Oliver Perry alone, on the other hand, portrays

him not only clean-shaven, but looking remarkably like a delicate

and romantic Japanese youth. A

painting of Oliver Perry alone, on the other hand, portrays

him not only clean-shaven, but looking remarkably like a delicate

and romantic Japanese youth. |

Perry’s son Oliver, painting

ca. 1854

Ryosenji Treasure Museum

|

|

|

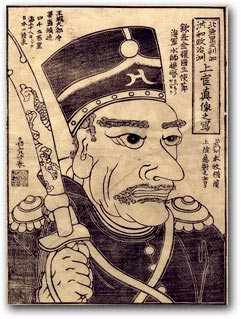

A well-known black-and-white kawaraban print of the commodore

hoisting a sheathed sword and wearing a strange brimless cap features

a thick mustache running parallel to bushy eyebrows.

Perry, kawaraban (broadsheet)

1854

Ryosenji Treasure Museum

|

A

scroll painted in Shimoda in 1854, on the other hand, renders him

with both bushy hair and beard and trim hair and beard—as if

he had gone to the barber and returned while the artist was still

at work.

Why all this facial hair? The explanation lies primarily in the power

of imaginative language: ever since the distant 16th- and early-17th-century

encounter, another derisive sobriquet for Westerners was “hairy

barbarians” (keto or ketojin).

|

|

Two images of

Perry from the “Black Ship Scroll,” 1854

Honolulu Academy of Art |

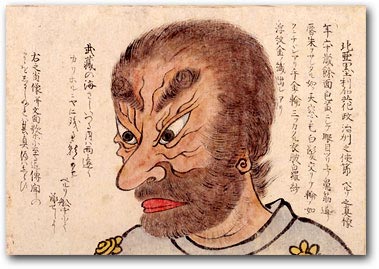

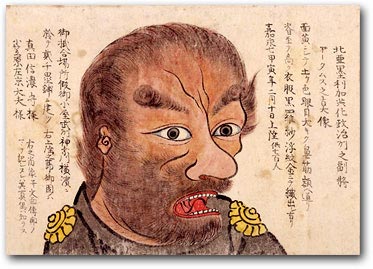

On rare occasion, the commodore’s hairy visage was transparently

barbaric and even demonic—as if the American emissary were truly

one of the legendary demons or devils (oni and akuma)

that old folktales spoke about as dwelling across the seas. The most

vivid such renderings are to be found in some truly alarming close-ups

of both Perry and Adams that also appear in the Shimoda scroll.

|

Portrait of Perry Portrait of Perry

from the “Black Ship Scroll”

Text: “True portrait of Perry, envoy of the Republic of North

America. His age is over sixty, complexion yellow, eyes slanted upwards,

nose impressive, lips red as if rouged. His hair is curled like rings

and mixed with gray. He wears three gold rings. His uniform is white

wool with raised crests woven in gold....”

Honolulu Academy of Art

|

|

|

Portrait of Adams

from the “Black Ship Scroll”

Text: “True portrait of Adams, Second in Command from the Republic

of North America. His complexion is yellow with an earthy tone, eyes

large, nose high-bridged. He is very tall. His uniform is black wool

with raised crests woven with gold....”

Honolulu Academy of Art |

Even

this Shimoda scroll, however, suggests that appearances could be deceiving.

The text that surrounds its ferocious “True Portrait of Perry”

also includes the following poem, which the commodore was imagined

to have composed on board his flagship:

Distant moon that appears

over the Sea of Musashi,

your beams also shine on California.

Apparently, even barbarians might have Japanese-style poetic souls.

Indeed, when it came to painting and describing Adams’ 15-year-old

son, who accompanied the mission, the “Black Ship Scroll”

practically fell all over itself in portraying him as a paragon of

polyglot virtues—delicate, aesthetic, muscular, martial, and

a model of filial piety. |

Portrait of Adams’ son from the “Black Ship Scroll”

Text:

“This youth is extremely beautiful. His complexion is

white, around his eyes is pink, his mouth is small, and his

lips are red. His body, hands, and feet are slightly plump,

and his features are rather feminine. He is intelligent by nature,

dutiful to his parents, and has a taste for the martial arts.

He likes scholarship, composes and recites poems and songs,

and reads books three lines at a glance. His power exceeds three

men, and his shooting ability is exceptional....”

Honolulu Academy of Art

|

|

As we shall see again in other renderings of interactions with the

Perry mission, the commodore and his fellow Americans were also

drawn from direct observation on occasion, and depicted as being

simply people of a different race and culture. Their features were

sharper than their Japanese counterparts. Their clothing differed.

They comported themselves in occasionally peculiar ways. Clearly,

however, they shared a common humanity with the Japanese.

An informal watercolor of Perry and Adams painted by Hayashi Shikyo

in 1854, for example, conveys an impression of the two men as officers

rather weary with responsibility.

|

Perry

(left) and Adams,

by Hayashi Shikyo, 1854

Peabody Essex Museum

|

|

Almost a half century later, Shimooka Renjo, who had actually participated

in one of the conferences with Perry, painted the commodore’s

portrait in watercolor and ink and mounted this as a traditional hanging

scroll (kakemono). Here was a Perry unlike those produced

in the tumult of the actual encounter: carefully executed, formal,

respectful, tinged with obvious Western painterly influence—and

still distinctively “Japanese.”

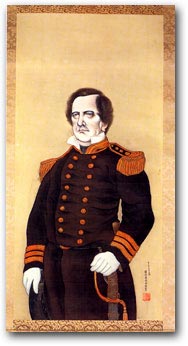

Kakemono (hanging scroll)

of Perry, by Shimooka Renjo

1901

Peabody Essex Museum

|

|

|