| |

Commemoration

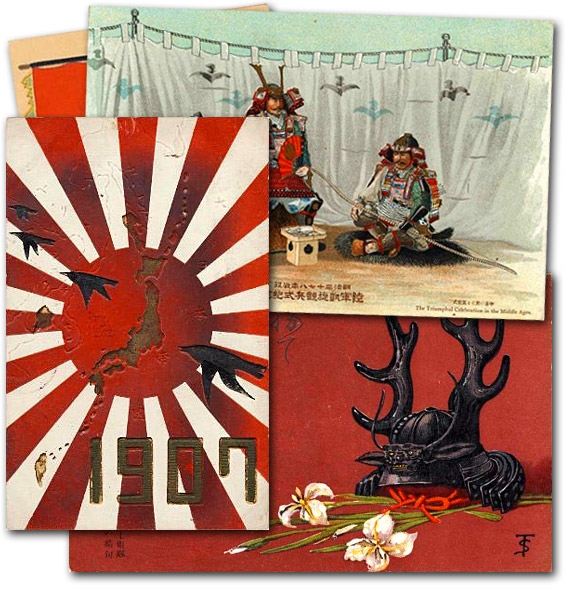

After the war ended, especially in 1906, both the government and private publishers issued postcards commemorating Japan’s victories—often in conjunction with parades and triumphal military reviews. (The three-card sinking ship with which this unit begins was published during these commemorations.) Some of these cards, especially those issued under official auspices, are conventional and predictable. At the same time, the government in particular also took this opportunity to promote “traditional” images from mytho-history and the age of the samurai that had rarely been played up during the war.

|

|

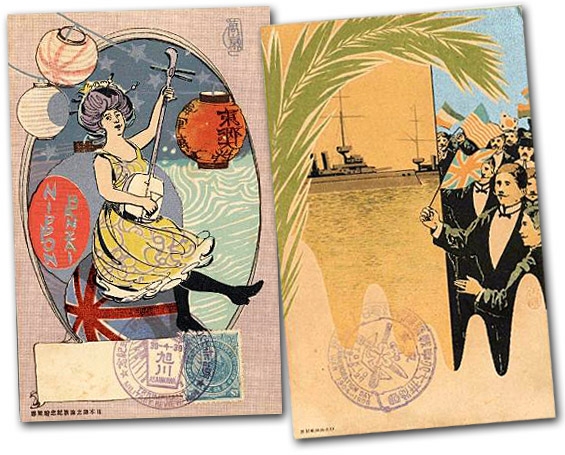

More striking by far, however, are postwar commemorative cards that carried the aestheticism seen in wartime graphics in ever more “modern” directions. These are not only highly Westernized, but again—certainly at first glance—sometimes seem to have little if any connection to war and destruction.

|

![“Goni Fair: In Commemoration of the Triumph” Artist unknown, 1906 [2002.1595] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](image/2002_1595_s.jpg) “Goni Fair: In Commemoration “Goni Fair: In Commemoration

of the Triumph,” 1906

[2002.1595]

|

This is the case, for example, with “triumphal” cards produced in conjunction with the 1906 Goni Fair, a trade show that had served since 1894 as a showcase for domestic crafts (ceramics, lacquerware, paper products, metalwork, etc.) and light industry (notably textiles). One Goni Fair postcard, for example, offers an art nouveau rendering of an elegant female representing sericulture. Stylized white moths rest along the line of her lithe body. Silk thread whirls gracefully behind her, against an abstract pattern of cocoons, while mulberry leaves form a border at the bottom. The woman’s garment itself is a hybrid of kimono sleeve and the wasp waist of fashionable Western gowns. All that actually connects this image to the recent war is a bilingual caption that reads (in the English): “Published for the Goni Fair in commemoration of the triumph.” |

A companion postcard from the same Goni Fair series features a roundel enclosing a lovely muse and lyre, resting above a Western-style musical score. Although a popular motif in European art nouveau, the Japanese touch is both subtle and unmistakable. An embossed chrysanthemum decoration graces the muse’s hair, and the musical score is Kimigayo (“His Majesty’s Reign”)—the unofficial emperor-centered national anthem that was composed in 1880, with lyrics taken from a tenth-century poem. (Basil Hall Chamberlain’s well-known 1890 translation of Kimigayo runs as follows: “Thousands of years of happy reign be thine; / Rule on, my lord, till what are pebbles now / By age united to mighty rocks shall grow / Whose venerable sides the moss doth line.”)

|

![“Muse and Musical Score in Commemoration of the Goni Fair” Artist unknown, 1906 [2002.1596] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](image/2002_1596_s.jpg) “Muse and Musical Score in “Muse and Musical Score in

Commemoration of the Goni Fair,” 1906

[2002.1596]

|

![“Woman Holding Floral Garland” from the series “Commemoration of the Victory of the Russo-Japanese War” by Ichijō Narumi, 1906 [2002.936] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](image/2002_0936_s.jpg) “Woman Holding Floral Garland” “Woman Holding Floral Garland”

from the series “Commemoration of

the Victory of the Russo-Japanese War”

by Ichijō Narumi, 1906

[2002.936]

|

Kimigayo was introduced to classrooms and public ceremonies in the 1890s as part of a campaign to pump up the mystique of the imperial institution. For historians today, it is a good example of how “reinvented traditions” were carefully manipulated to buttress Japan’s modern nationalism. With this little postcard, the resuscitated old poem went beyond the upholstery of a Western musical setting to acquire an up-to-date art nouveau gloss!

In another more restrained art nouveau rendering from 1906, an elegant kimono-clad woman holds up a wreath of flowers. Only the title of the series from which this postcard comes, “Commemoration of the Victory of the Russo-Japanese War,” makes clear that this too is a celebration of martial triumph.

|

Other postwar postcards replicate the exuberance of wartime renderings of home-front celebrations and lantern parades—sometimes with an illuminating international spin. One such graphic, celebrating the first anniversary of Admiral Tōgō’s May 1905 victory, offers men in formal dress waving British, American, French, and Japanese flags. The identity of the crowd is unclear—are these men a mix of nationalities? Japanese waving a variety of flags?—but the viewer is left with the understanding that Japan has taken its place among the great powers of the world, which all cheer its triumph. A more startling graphic in the same series picks up the lantern-parade theme with a vivacious, bare-shouldered Japanese woman strumming a samisen while sitting on a lantern with the markings of the British flag—obviously a salute to the Anglo-Japanese Alliance that enabled Japan to take on Russia without fear of another nation coming in on the enemy’s side. Roman letters on one lantern read Banzai Nippon; Japanese writing on another celebrates Admiral Tōgō and the imperial navy.

|

|

“Banzai Nippon, Banzai Admiral Tōgō”

from the series “The Battle of the Japan

Sea Commemorative Postcards,” 1906

[2002.1583]

|

“Commemoration of the Battle of

the Japan Sea,” 1906

[2002.5199] |

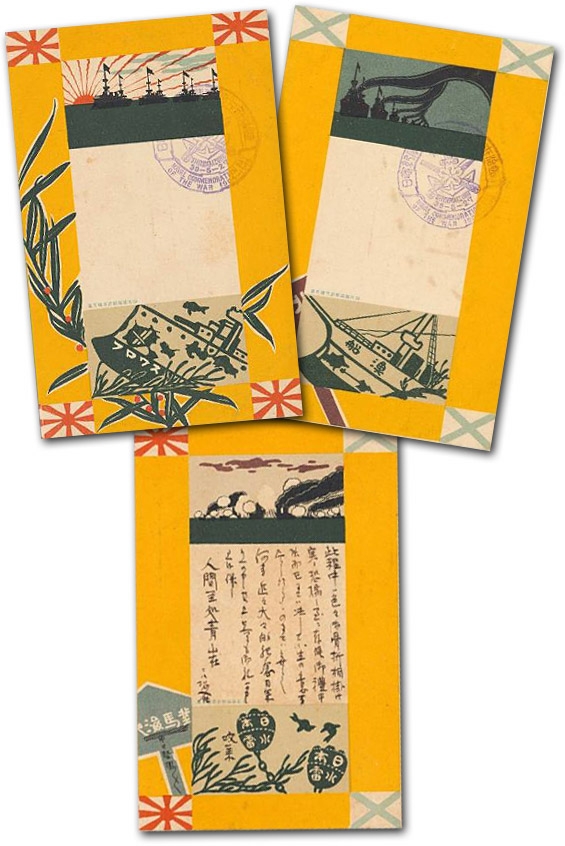

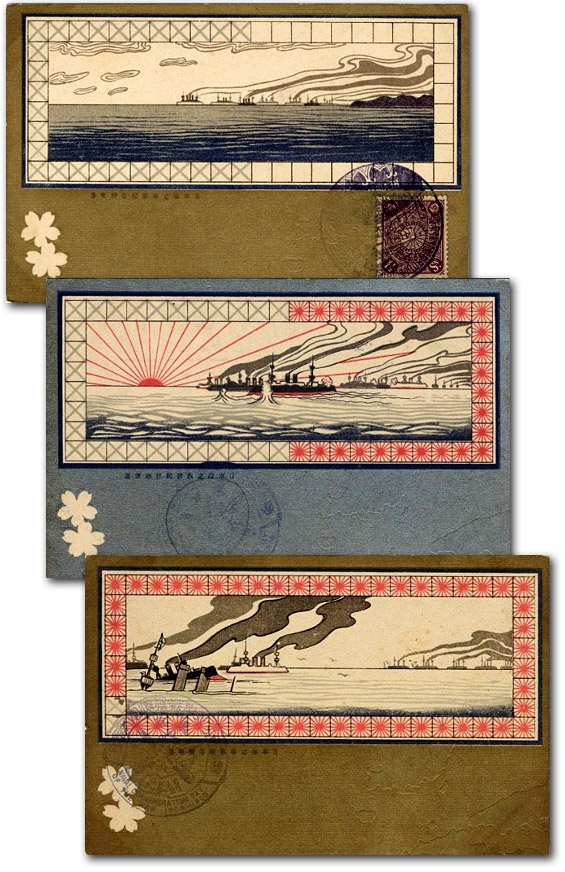

Other postwar commemorative postcards are less humanized but hardly less innovative as plain design. In several three-card sets celebrating the victory over the Baltic Fleet in May 1905, for example, subject and design are wedded in the most subtle manner imaginable. The Russian fleet alone is framed with a border featuring the enemy’s simple “X” flag (more properly known as the St. Andrew Blue Cross). Where the two fleets engage each other, the border becomes half the Russian ensign and half the Japanese sun-with-rays military flag. With Japan’s decisive victory the sun-with-rays motif becomes dominant. In one of these sets, only two Russian flags remain in the border, near the forlorn funnels of a sunken ship.

|

|

Some postcard sets celebrating the first anniversary of the destruction of the Russian fleet in 1905 made innovative use of borders that featured Japan’s sun-with-rays military flag and the blue-and-white St. Andrew Cross flown on Russian warships. One of the graphics above includes underwater mines floating amidst fish and seaweed. Some postcard sets celebrating the first anniversary of the destruction of the Russian fleet in 1905 made innovative use of borders that featured Japan’s sun-with-rays military flag and the blue-and-white St. Andrew Cross flown on Russian warships. One of the graphics above includes underwater mines floating amidst fish and seaweed.

“Commemoration of the Battle of the Japan Sea”

[2002.5201] [2002.5202] [2002.5203]

|

|

“Battle Scenes” from the set “Commemorative Postcards of “Battle Scenes” from the set “Commemorative Postcards of

Naval Battles in the Japan Sea”

[2002.1573] [2002.1574] [2002.1575]

|

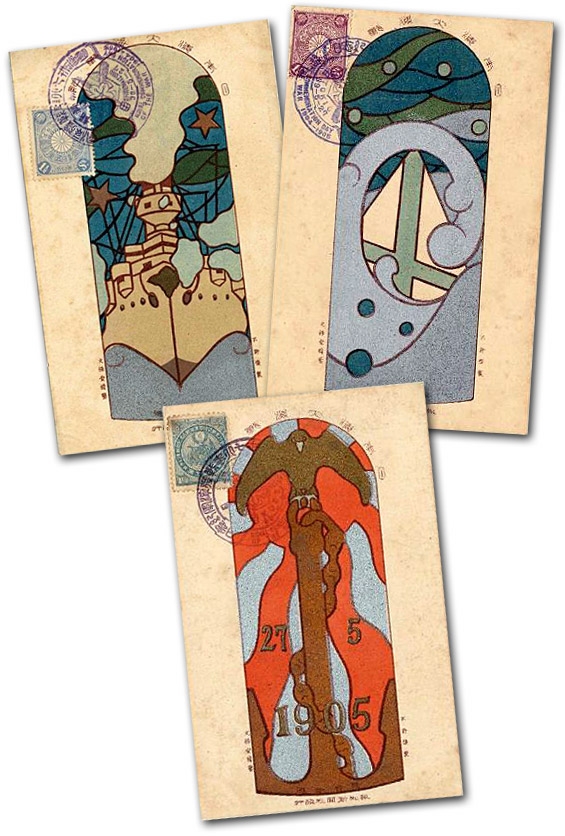

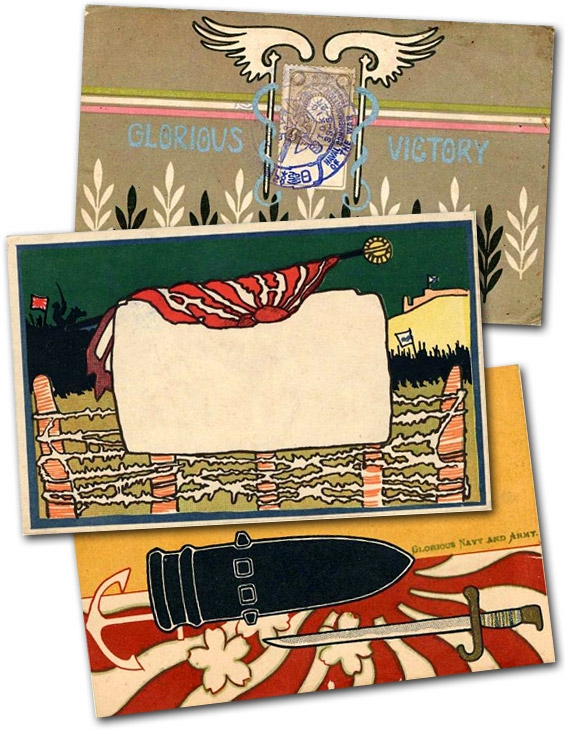

Another 1906 celebration of Admiral Tōgō’s great victory found inspiration in the “stained-glass” style fashionable in contemporary European and American design. Other artists turned artifacts of war as mundane as barbed wire and artillery shells into attractive emblems of Japan’s glorious victory.

|

|

These handsome 1906 cards celebrating the anniversary of Admiral Tōgō’s decisive victory over the Russian Baltic Fleet on May 27, 1905 feature the “stained glass window” effect associated with European art nouveau designs. These handsome 1906 cards celebrating the anniversary of Admiral Tōgō’s decisive victory over the Russian Baltic Fleet on May 27, 1905 feature the “stained glass window” effect associated with European art nouveau designs.

“Battleship” from the series “Commemoration of the

Naval Battle of the Japan Sea”

[2002.1591]

“Waves Swallowing the Russian flag” from the series

“Commemoration of the Naval Battle of the Japan Sea”

[2002.1594]

“Eagle and Anchor” from the series

“Commemoration of the Naval Battle of the Japan Sea”

[2002.1593]

|

|

Even mundane items such as barbed wire and artillery shells became aesthetic motifs in the postwar celebrations of “glorious victory.” Even mundane items such as barbed wire and artillery shells became aesthetic motifs in the postwar celebrations of “glorious victory.”

“Glorious Victory,” 1906

[2002.5148]

“Japanese Flag with Battle Scene in Background,” 1906

[2002.1567]

“Glorious Navy and Army,” 1906

[2002.5209]

|

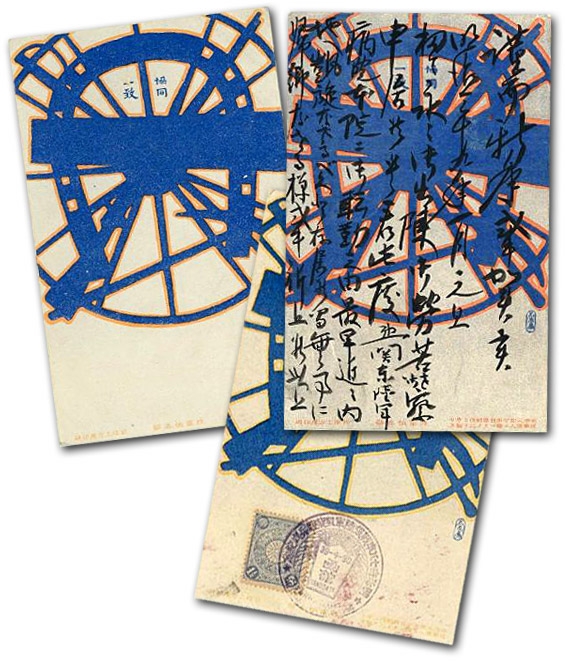

A 1906 commemorative postcard bearing the slogan “unity through cooperation” (kyōdō itchi) captures much of the energy, vision, and elan of these celebratory graphics. Here the intricate design, blue against a grey background, draws on plain items to suggest how many disparate forces had to come together before the army could emerge victorious. It includes a horseshoe (for cavalry), cannon barrel (heavy artillery), rifle (infantry), saber (officer corps), wagon wheel (supply, logistics), and pickaxe (labor, construction)—all folded into a harmonious whole.

|

|

This postwar design extolling “unity through cooperation” incorporates symbols of various units of the armed forces. The three cards above reflect the various forms in which postcards have survived for contemporary collectors—in their original pristine form, with stamps and cancellations indicating the commemorative date of issue, and with an actual message brushed over the design (the reverse side being reserved for the mailing address). This postwar design extolling “unity through cooperation” incorporates symbols of various units of the armed forces. The three cards above reflect the various forms in which postcards have survived for contemporary collectors—in their original pristine form, with stamps and cancellations indicating the commemorative date of issue, and with an actual message brushed over the design (the reverse side being reserved for the mailing address).

“Unity through Cooperation,” 1906

[2002.2258]

with stamped cancellation (bottom)

[2002.2257]

with hand-written message (right)

[2002.2259]

|

The design is sophisticated, elegant, and up-to-date. War is made modern and beautiful. Unity is extolled—and no Japanese would have failed to understand that this meant mobilizing not merely the army and navy, but the nation as a whole. Artists and their commercial publishers were themselves an intimate part of such patriotic mobilization. So were the consumers of postcards. (Serendipitously but fittingly, this postcard involved the collaboration of two artists.)

As it happens, this particular graphic has survived in various forms that remind us of the various roles postcards played. It has come down plain, as the design sent out to market; with a stamp and cancellation on the picture side, in all likelihood done by a collector; and as mail, a real item of correspondence, with a personal message brushed over the entire picture side. The card with writing on it was sent to a veteran in a military hospital, congratulating him for his valor and wishing him a speedy recovery.

Typical in its modish style, which is usually associated with the vogue of art nouveau, the “unity through cooperation” postcard is also a small but concrete reminder of how rapidly the world was changing. This is a wedding of art and propaganda and popular war “reportage” very different from the woodblock prints that had been so overwhelmingly popular only a decade previously. The Western influence in both technology and style is unmistakable. Indeed, it is known that Japanese artists who visited the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900 were particularly impressed by art nouveau. But as Anne Nishimura Morse and other art historians have pointed out, “cultural influence” was also moving in the opposite direction. Art nouveau itself, after all, was strongly influenced by Western admiration of Japanese art.

While Europeans and Americans may not have grasped the dynamism of such circular aesthetic and cultural influences, they certainly did see that Japan was now a major player on the world scene—a far cry from the backward society Commodore Perry had encountered almost exactly a half century before the Russo-Japanese War. How these foreigners visualized the war, and the Japanese who were fighting it, is another story.

It is a story, moreover, that also can be told in good part through the picture-postcard boom that made the war between Imperial Japan and Tsarist Russia a truly global spectacle.

|

On viewing images of a potentially disturbing nature: click here.

Images from the Leonard A. Lauder Collection of Japanese Postcards at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Unless otherwise indicated, all are by unidentified artists and date from the 1904-1905 war years.

|

|

|

|

|