| |

Heroes & Heroines

By sheer happenstance, the history of postcards overlaps with the early history of modern Japan. In Europe, postcards first appeared in Austro-Hungary at the very end of the 1860s and quickly spread to other nations. Their origin thus coincides with the Meiji Restoration of 1868 that saw the overthrow of the feudal regime and genesis of the modern Japanese state. In the early 1870s, the Japanese government modeled its postal system after that of Great Britain and commenced issuing plain postcards on which the address was written on one side and a message on the other. By the late 1880s, as Anne Nishimura Morse (curator of the stunning Leonard A. Lauder Collection of Japanese Postcards at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) has noted, this was the most popular form of mail in Japan.

In Europe, issuance of privately printed postcards was authorized in 1898. The Japanese government followed suit two years later, paving the way for manufacturers to enter the market and compete for consumers with attractive graphics. (Until 1907, the address took up the blank side of the card in Japan, and messages had to be written on the illustrated side.)

With the outbreak of the war in 1904, manufacturers found a huge audience hungry for the appealing mix of war coverage and visual entertainment that postcards provided. Apart from some official sets issued in large printings by the Ministry of Communications, it is estimated that around 4,500 different designs were commercially produced in Japan commemorating the war, with print runs usually in the neighborhood of one to three thousand. Shops that had featured woodblock prints during the earlier conflict with China became natural purveyors of these new graphics; by the end of the war, there were more than four thousand such outlets in Tokyo alone.

Kendall Brown, writing about the Lauder collection, has observed that postcards quickly became “both symbols and vehicles of modernity” in Japan. Mass production, consumerism, commercial art, homogenization and democratization of culture, the emergence of “middle-class” tastes—all this was part and parcel of the postcard phenomenon. So was a new sense of “internationalism,” since these cards crossed national boundaries and became more than just mail. They became advertisements for national cultures and national glories. They contributed to the popularity of international “pen pals.” They became collectors’ items, frequently issued in sets and series or with captions in several languages.

The transformation in visualizing modern war (and modern times more generally) that took place in Japan between the wars against China and Russia emerges vividly when we juxtapose celebratory woodblock prints from the earlier war and postcards commemorating victory in the latter. In a well-known woodblock triptych by Kobayashi Kiyochika, for example, a Chinese cruiser torpedoed off the Yalu River in 1894 sinks beneath the waves. We behold the stricken warship underwater, corpses of its crew suspended in the brine.

|

![“Picture of Our Naval Forces in the Yellow Sea Firing at and Sinking Chinese Warships” by Kobayashi Kiyochika, October 1894 [2000.380.22a-c] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](image/2000_380_22_sss.jpg) |

This stunning woodblock triptych from the Sino-Japanese War foreshadows some of the more avant-garde artwork that emerged in postcards of the Russo-Japanese War ten years later. This stunning woodblock triptych from the Sino-Japanese War foreshadows some of the more avant-garde artwork that emerged in postcards of the Russo-Japanese War ten years later.

“Illustration of Our Naval Forces in the Yellow Sea Firing at and Sinking Chinese Warships” by Kobayashi Kiyochika, October 1894

[2000.380.22a-c] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

|

Much the same striking image of a stricken enemy vessel is reprised in a postcard set published in 1906 in commemoration of “the great battle of the Sea of Japan” that took place on May 27, 1905. In this celebrated victory, Admiral Tōgō managed to sink Russia’s Baltic Fleet (which had sailed around the world to meet its doom). Here three postcards combine to make the scene, and the artist’s vision and style are both similar to Kiyochika and strikingly different. The islands of Japan are introduced as almost abstract geometry. The enemy ship, flattened into a black and red silhouette, sinks through a grid of serrated parallel lines representing waves. Admiral Tōgō’s victorious warships float like white ghosts (or angels) high in the scene, red dots no bigger than pinheads signaling the rising sun flag. Text at the bottom of each card states that the design was produced for a competition sponsored by a newspaper company. The artist (whose name is not given) was clearly inspired by the vogue of European art nouveau.

|

![“Commemorating the Great Naval Battle of Japan Sea,” Artist unknown 1906 [2002_1577] [2002_1576] [2002_1578] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](image/2002_1577_1576_1578_s.jpg) |

|

|

These three postcards commemorating the Russo-Japanese War form a “triptych” that is strikingly similar to Kiyochika’s famous woodblock print—and at the same time dramatically innovative and modern. These three postcards commemorating the Russo-Japanese War form a “triptych” that is strikingly similar to Kiyochika’s famous woodblock print—and at the same time dramatically innovative and modern.

“Commemorating the Great Naval Battle of Japan Sea,” three-postcard series presented as a single image (top) and as separate cards (bottom), 1906

[2002.1577] [2002.1576] [2002.1578]

|

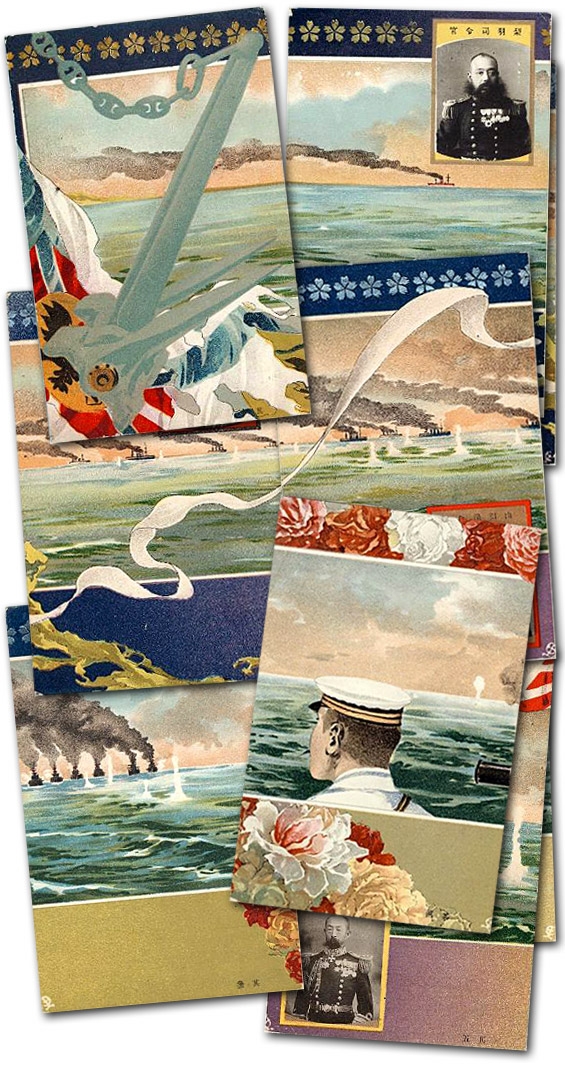

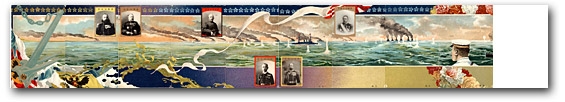

This impression of entering a significantly altered and “up-to-date” world also comes through vividly when we set a more extended set of postcards commemorating Tōgō’s 1905 triumph against comparably sweeping woodblock panoramas. Designed by Saitō Shōshū and made up of ten cards that fit together like fine joinery, this commercial tour de force combines an expansive painterly vista of sea and ships with elaborate borders top and bottom, all studded with that most “realistic” of contemporary representations: photo portraits of the Japanese commanders.

|

|

|

The art of the postcard was elevated to a truly sumptuous level in this extended series by Saitō Shōshū depicting “The Battle of the Japan Sea” in 1905. (One card in the set [far right] has yet to be found.) Elegant and intricate compositions such as this reveal the broader appeal of postcards as a popular art form to be collected as well as used as an everyday means of communication. The art of the postcard was elevated to a truly sumptuous level in this extended series by Saitō Shōshū depicting “The Battle of the Japan Sea” in 1905. (One card in the set [far right] has yet to be found.) Elegant and intricate compositions such as this reveal the broader appeal of postcards as a popular art form to be collected as well as used as an everyday means of communication.

|

Woodblock artists also turned their hand to panoramic naval battles. In the jubilation over Admiral Tōgō’s successful surprise attack against the Russians in February 1904, for example, Yasuda Hanpō churned out a six-block “Illustration of the Furious Battle of Japanese and Russian Torpedo Destroyers outside the Harbor of Port Arthur.” Set against postcard art like Saitō’s assemblage, these ambitious prints suddenly seem modest and old fashioned. Certainly, that is how Japanese of the new century came to regard them. By the time Admiral Tōgō dispatched the Baltic Fleet (15 months after the initial surprise attack), woodblock war prints had all but disappeared from the scene.

|

![“Illustration of the Furious Battle of Japanese and Russian Torpedo Destroyers outside the Harbor of Port Arthur” by Yasuda Hanpō, 1904 [2000.72a-f] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](image/2000_072_s.jpg) |

Panoramic woodblock prints such as this six-block depiction of the opening naval battle between the Japanese and Russian fleets quickly fell into disfavor in the face of the postcard vogue. Panoramic woodblock prints such as this six-block depiction of the opening naval battle between the Japanese and Russian fleets quickly fell into disfavor in the face of the postcard vogue.

“Illustration of the Furious Battle of Japanese and Russian Torpedo Destroyers outside the Harbor of Port Arthur” by Yasuda Hanpō, 1904

[2000.72a-f] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

|

The melding of disparate images and design elements in a fluid montage that characterizes Saitō’s evocative set was typical of the times—yet one more expression of being temperamentally and stylistically up-to-date. More than popular artists in other countries, the Japanese frequently set photos in painterly settings or drew on their rich tradition of design to make each card a tasteful and original composition. In a broader sense the postcard genre itself, taken as a whole, became an almost boundless montage that drew together an expansive range of “modern” images.

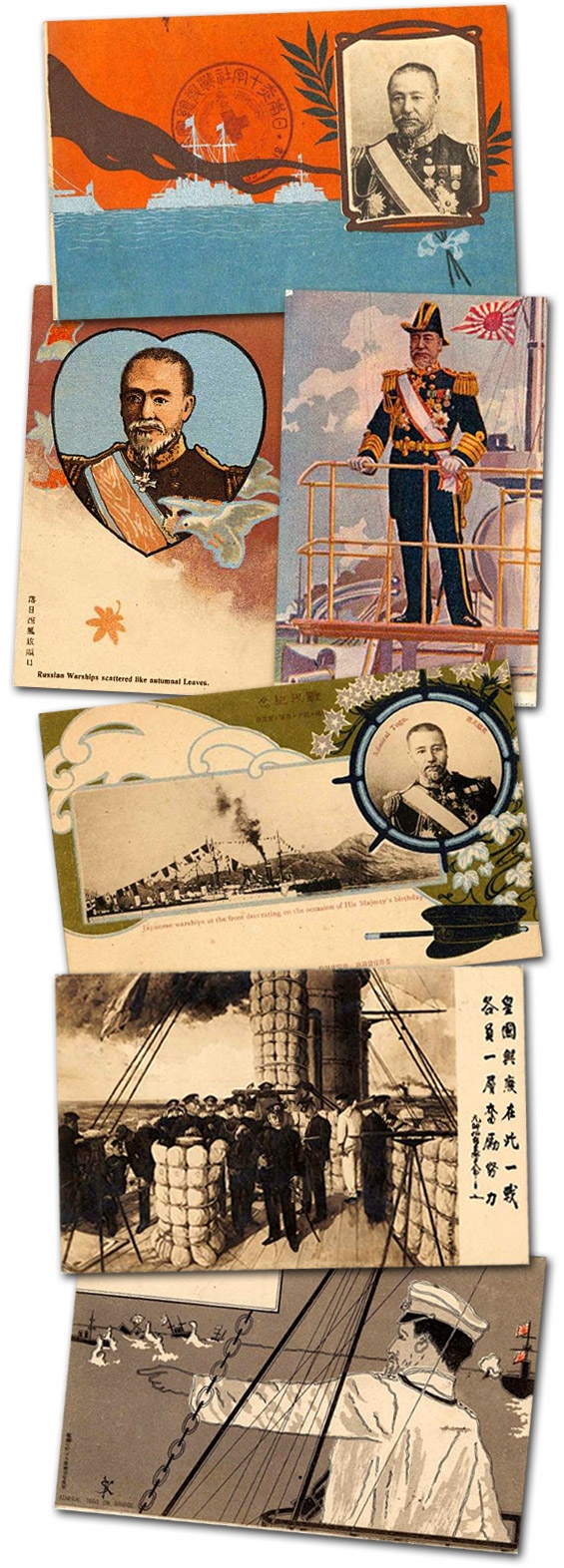

The portraits of individual naval commanders embedded in Saitō’s panorama also reflected something new on the scene: not merely singling out contemporary heroes (an old practice indeed), but turning them into celebrities with instantly recognizable faces. In the circumstances, most of these modern heroes were military officers and civilian statesmen; and none was accorded greater popular veneration than Admiral Tōgō. Tōgō became the prototype of what came to be known in early-20th-century Japan as the gunshin or “military god.”

In Saitō’s set, Tōgō’s was but one of six portraits. No other hero, however, graced more individual postcards or was presented in so many different stylistic ways. Sometimes he appears with no caption at all; sometimes the card carries a short caption in both Japanese and English. Certain iconic photo portraits are replicated in drawings. In one rendering, the admiral’s benign visage peers out from the most “Western” of frames, a perfect heart—and is accompanied by the most Japanese of touches, a poem linking war and the beauty of nature (“Russian warships scattered like autumnal leaves”).

|

|

Scores of postcards celebrated the exploits of military heroes such as Admiral Tōgō, who began the war in 1904 by driving the Russian Far Eastern Fleet into Port Arthur and blockading it there, and whose devastation of the Russian Baltic Fleet in the great battle of Tsushima in May 1905 marked the closing stage of the war. Postcards, with their great stylistic variety, contributed greatly to the war myths and celebrity cults spawned in Japan by the Russo-Japanese War. Scores of postcards celebrated the exploits of military heroes such as Admiral Tōgō, who began the war in 1904 by driving the Russian Far Eastern Fleet into Port Arthur and blockading it there, and whose devastation of the Russian Baltic Fleet in the great battle of Tsushima in May 1905 marked the closing stage of the war. Postcards, with their great stylistic variety, contributed greatly to the war myths and celebrity cults spawned in Japan by the Russo-Japanese War.

“Admiral Tōgō and Battleships” 1906

[2002.3651]

“Russian Warships Scattered Like Autumnal Leaves” (left)

[2002.3613]

“Admiral Tōgō, the Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Squadron” (right)

[2002.5457]

“Official Commemoration Card: Japanese Warship at the Front Decorated

on the Occasion of His Majesty's Birthday, with Admiral Tōgō”

[2002.4193]

“Painting of Admiral Tōgō on Deck”

(with hand-written message)

[2002.2942]

“Admiral Tōgō on the Bridge”

[2002.1410]

|

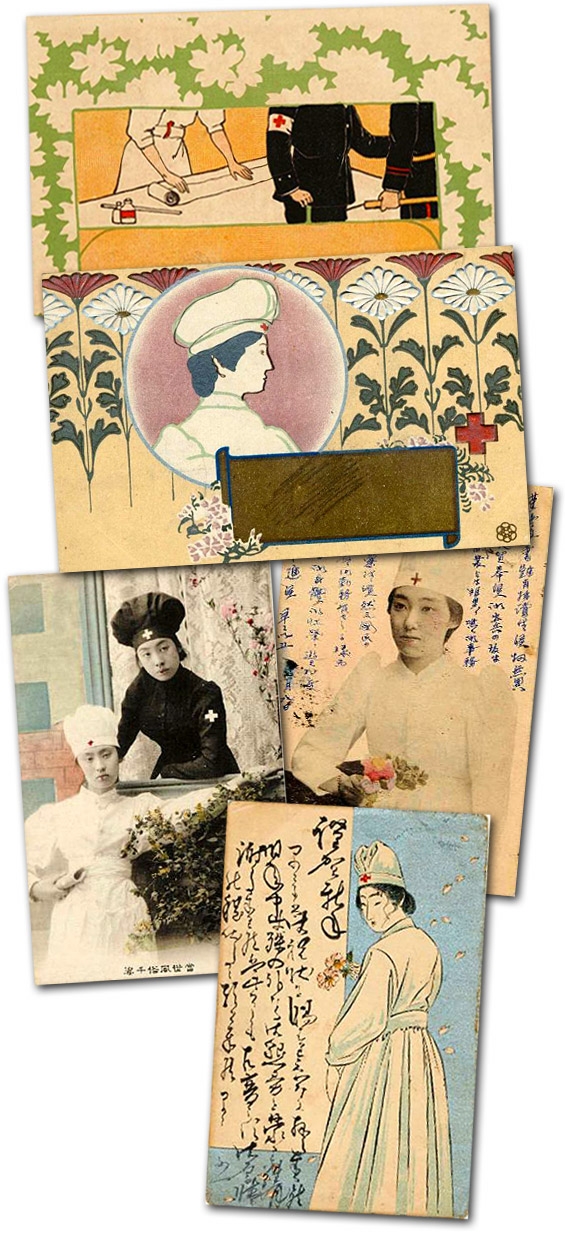

Postcard artists also took care to personalize another new manifestation of the nation’s modern identity: its embrace of the International Red Cross. War with Russia was more than a demonstration of military might. It was simultaneously a showcase of the nation’s worthiness to stand alongside the “civilized” nations of the world—and there was no better way of demonstrating this than by behaving humanely to captured and wounded enemy in accordance with principles exemplified by the Red Cross. (The Red Cross was founded in 1863 and convened its first international conference in 1867, just months before the Meiji Restoration took place in Japan. The pertinent Geneva Conventions concerning treatment of wounded enemy were adopted in 1864, and the Hague Conventions governing “laws and customs of war” were adopted in 1899, between the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars.)

|

![“Nurse from Tokyo Nichinichi shinbun” [2002_3600] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](image/2002_3600_s4293_Copy.jpg) |

Postcards featuring the Red Cross thus resonated with many overlapping themes. Here again, in style as well as subject, they made the nation’s modernity available for all to see. At the same time, they reminded viewers of the personal sacrifices of the country’s fighting men and—by featuring female nurses—the purity and nurturing qualities of its women. With their comely nurses, moreover, the Russo-Japanese War artists also neatly updated an old tradition of “pictures of beauties” (bijin-e). More than a few postcard nurses carried an erotic charge. Some, indeed—including photos as well as drawings—essentially amounted to “pinup girls” and were sent to soldiers and sailors who treasured them as such.

“Nurse from Tokyo Nichinichi shinbun”

[2002.3600]

|

|

Many postcards called attention to Japan’s civilized conduct and embrace of humanitarian ideals by depicting its participation in the International Red Cross. A conspicuous element of modern “pin-up” girls entered the picture in portrayals of beautiful Red Cross nurses. Many postcards called attention to Japan’s civilized conduct and embrace of humanitarian ideals by depicting its participation in the International Red Cross. A conspicuous element of modern “pin-up” girls entered the picture in portrayals of beautiful Red Cross nurses.

“Nurse and Soldiers” 1906

[2002.3597]

“Red Cross Nurse” by Kaburaki Kiyokata

[2002.953]

“Nurse Holding a Branch of Camellia” (right,

with hand-written message)

[2002.3594]

“Nurses” from the series “Thousand Contemporary Figures” (left)

[2002.3599]

“Nurse Holding a Cherry Blossom Branch” (with hand-written message)

[2002.3593]

|

Occasionally postcards offered the novelty feature of revealing something new when held to the light. In one of these (marked “hold card to light” in English), a nurse handsome as any woodblock-print beauty gazes down on what illumination reveals to be not just a wounded soldier in bed, but a wounded Russian. (No identification is necessary: his features are craggy and his nose is enormous.)

|

![“Nurse Looking Over a Wounded Soldier” [2000_1572] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](image/2002_1572_s.jpg) ![“Nurse Looking Over a Wounded Soldier” [2000_1572b] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Bosto](image/2002_1572b_s.jpg) |

“Show-through” postcards, which sometimes carried instructions in English, revealed hidden images when held to the light. Here the patient is transparently a wounded Russian, as his craggy features and prominent nose make abundantly clear. “Show-through” postcards, which sometimes carried instructions in English, revealed hidden images when held to the light. Here the patient is transparently a wounded Russian, as his craggy features and prominent nose make abundantly clear.

“Nurse Looking Over a Wounded Soldier”

[2002.1572] [2002.1572b]

|

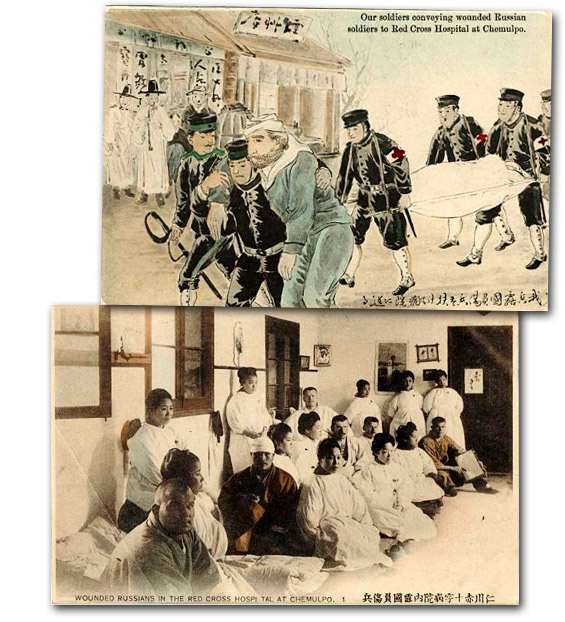

Here was a confluence of impressions indeed: war as healing, with a classic Japanese beauty in Western garb, a whiff of romance, and a reassuring propaganda message concerning the nation’s adherence to international humanitarian norms. Usually, such propaganda did not require holding cards to the light. Japanese medics were portrayed tending wounded Russians on the battlefield. Nurses posed for group photographs with their burly Russian patients.

|

|

The Japanese took great care to portray their humane treatment of wounded Russians. Captions frequently were given in English as well as Japanese. The Japanese took great care to portray their humane treatment of wounded Russians. Captions frequently were given in English as well as Japanese.

“Our Soldiers Conveying Wounded Russian Soldiers to

Red Cross Hospital at Chemulpo” 1906

[2002.5119]

“Wounded Russians in the Red Cross Hospital at Chemulpo”

[2002.2965]

|

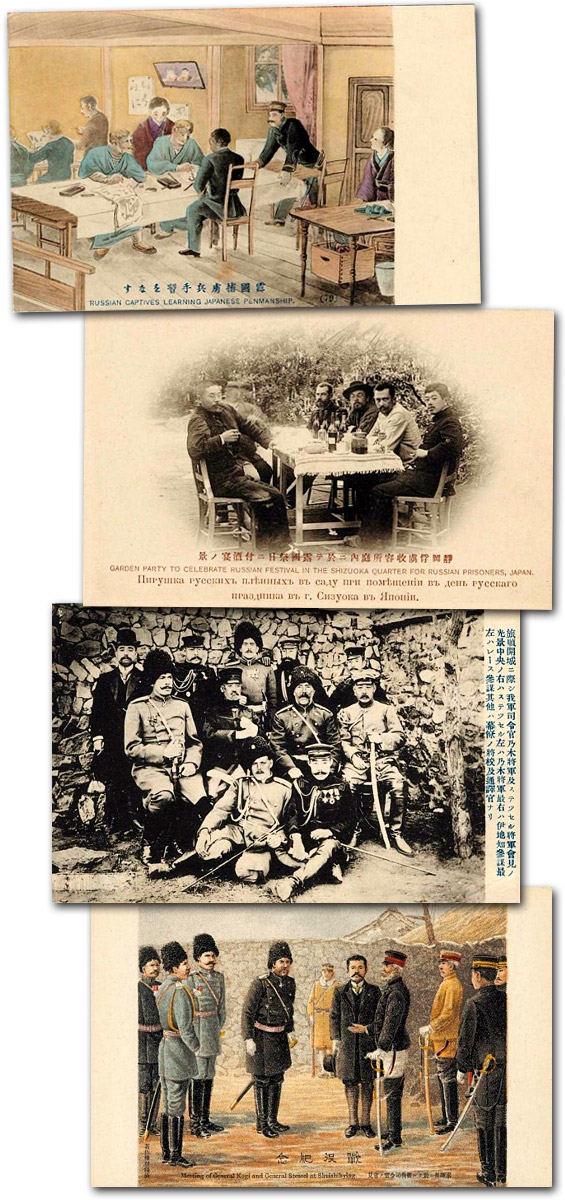

Such solicitous care, the postcards suggested, extended to prisoners and defeated foe in general. One series of softly rendered drawings, for example, includes the unexpected scene of captured Russians learning Japanese calligraphy. Another postcard, captioned in Russian as well as English and Japanese, features an artsy photograph of Japanese joining POWs at an outdoor party celebrating a Russian holiday. After hard-fought battles, it was not uncommon for the high command of both sides, Japanese victors and Russian vanquished, to pose for a collegial photo together or be “commemorated” in a dignified official color lithograph.

|

|

Japanese postcard propaganda sometimes romanticized the war almost as a benign cultural exchange—as seen in the above scenes of Russian POWs learning calligraphy and celebrating a holiday. Other postcards emphasized the common humanity (and shared elitism) of high-ranking officers on both sides who came together in the wake of Japanese victories. Japanese postcard propaganda sometimes romanticized the war almost as a benign cultural exchange—as seen in the above scenes of Russian POWs learning calligraphy and celebrating a holiday. Other postcards emphasized the common humanity (and shared elitism) of high-ranking officers on both sides who came together in the wake of Japanese victories.

“Russian Captives Learning Japanese Penmanship”

[2002.3440]

“Garden Party to Celebrate Russian Festival in the Shizuoka Quarter

for Russian Prisoners, Japan,”

[2002.3287]

“Meeting of General Stoessel and General Nogi upon the

Surrender of Port Arthur”

[2002.3275]

“Official Commemoration Card: Meeting of General Nogi

and General Stoessel at Shuishiying”

[2002.4201]

|

On viewing images of a potentially disturbing nature: click here.

Images from the Leonard A. Lauder Collection of Japanese Postcards at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Unless otherwise indicated, all are by unidentified artists and date from the 1904-1905 war years.

|

|

|

|

|