| |

When push came to shove, however, even-handedness proved difficult if not impossible for foreign cartoonists to maintain. In the final analysis, race mattered. The Japanese were yellow, the Russians white, and the spectacle of Asia rising was forbidding and even terrifying.

Thus Bianco, who seemed so balanced in his portrayal of Roosevelt saying “Enough!” to carnage, also introduced postcard collectors to “the great duel between yellow and white.” In this, the American president and other bystanders (representing France, Germany, and England) are spectators to a wrestling match between the Russian bear (a white polar bear standing on legs marked Korea and Manchuria) and the emperor of Japan, clad in a yellow kimono. The emperor is smaller in stature, but seemingly more adept. And, almost completely hidden, he has a secret weapon in the form of a dagger in his hand—presumably a subtle allusion to the stab-in-the-back of the surprise naval attack with which Japan opened the war.

|

![“The Great Duel between Yellow and White” Artist unknown [2002_3764] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts Boston](image/2002_3764_s.jpg) |

“The Great Duel between Yellow and White”

[2002.3764]

|

In this “Great Duel between Yellow and White,” the United States, France, Germany,

and England look on as Japan (the emperor in a conspicuously yellow kimono) tries to

knock the white Russian polar bear off its legs (labeled Korea and Manchuria). All but

invisible is a dagger in the emperor’s hand. In this “Great Duel between Yellow and White,” the United States, France, Germany,

and England look on as Japan (the emperor in a conspicuously yellow kimono) tries to

knock the white Russian polar bear off its legs (labeled Korea and Manchuria). All but

invisible is a dagger in the emperor’s hand.

|

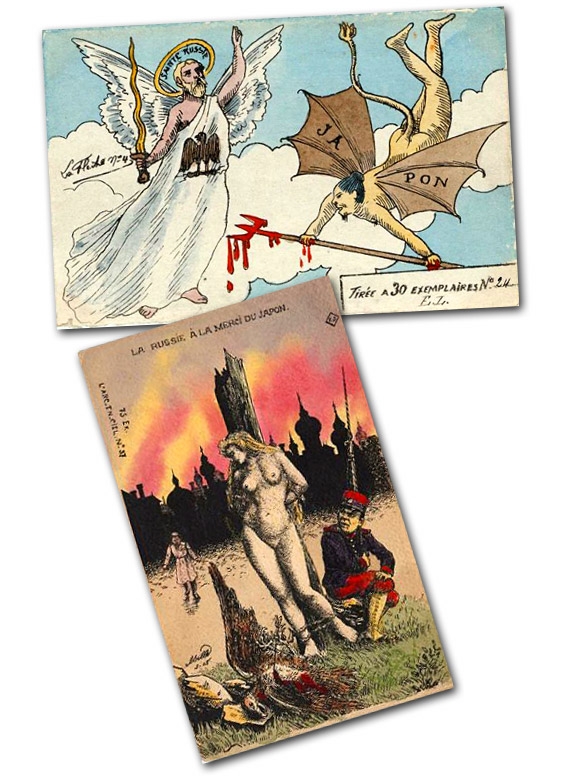

Postcard intimations of the Yellow Peril took many forms. Indeed, it seems fair to say that no other means of communication affords such a concentrated and accessible (and full-color) sample of this racial animus on the part of Westerners. The treatment might be witty—an angelic “Saint Russia” confronting a yellow Japanese devil with a blood-stained pitchfork in the clouds. It might be heavy with intimations of civilizational rape—in this case a beautiful blonde nude woman tied to a stake “at the mercy” of a leering, heathen Japanese soldier crouched at her feet. Russia itself is aflame in the background, threatened by revolutionary upheaval within and the revolutionary rise of Asia outside.

|

|

In this confrontation between “Saint Russia” and a Japanese devil (top), intimation of a conflict between Good and Evil is treated lightly, almost as a joke. By contrast, “Russia at the Mercy of Japan” (bottom) offers a truly satanic image of Russia (or the West) as a pure, white virgin tied to the stake and facing an unspeakable fate at the hands of the ominous crouching yellow man. Moscow already lies in flames in the background. In this confrontation between “Saint Russia” and a Japanese devil (top), intimation of a conflict between Good and Evil is treated lightly, almost as a joke. By contrast, “Russia at the Mercy of Japan” (bottom) offers a truly satanic image of Russia (or the West) as a pure, white virgin tied to the stake and facing an unspeakable fate at the hands of the ominous crouching yellow man. Moscow already lies in flames in the background.

“Saint Russia and Devil Japan”

[2002.6796]

“Russia at the Mercy of Japan”

[2002.6831]

|

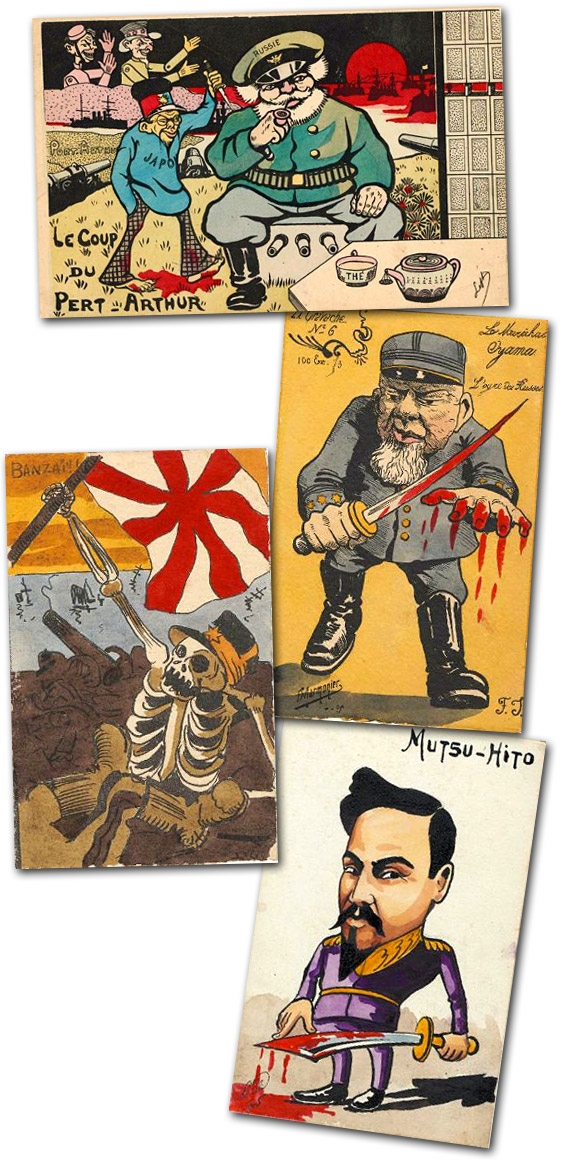

The yellow man’s stab-in-the-back at Port Arthur attracted colorful French attention, with the English and Americans depicted applauding in the background. (It was not until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor over three decades later that Americans really found such surprise tactics reprehensible.) This carried over—again, most conspicuously in French graphics—to a gallery of Japanese leaders wielding blood-stained swords, or hoisting a “Banzai!” flag of death.

|

|

The Japanese menace is conveyed in these four graphics not only by turning General Oyama and the Meiji emperor into murderers, and the Japanese military into a macabre skeleton shouting “Banzai!,” but also by depicting Japan’s surprise attack on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur at the outset of the war as a sinister stab in the back (top). Britain and the U.S. applaud as the little yellow man (with sinister long toenails!) prepares to execute his dastardly deed. The Japanese menace is conveyed in these four graphics not only by turning General Oyama and the Meiji emperor into murderers, and the Japanese military into a macabre skeleton shouting “Banzai!,” but also by depicting Japan’s surprise attack on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur at the outset of the war as a sinister stab in the back (top). Britain and the U.S. applaud as the little yellow man (with sinister long toenails!) prepares to execute his dastardly deed.

“The Blow of Port Arthur”

[2002.6804]

“Marshal Oyama” (right)

[2002.3812]

“Banzai!”

[2002.3823]

“Mutsu-hito”

[2002.3824]

|

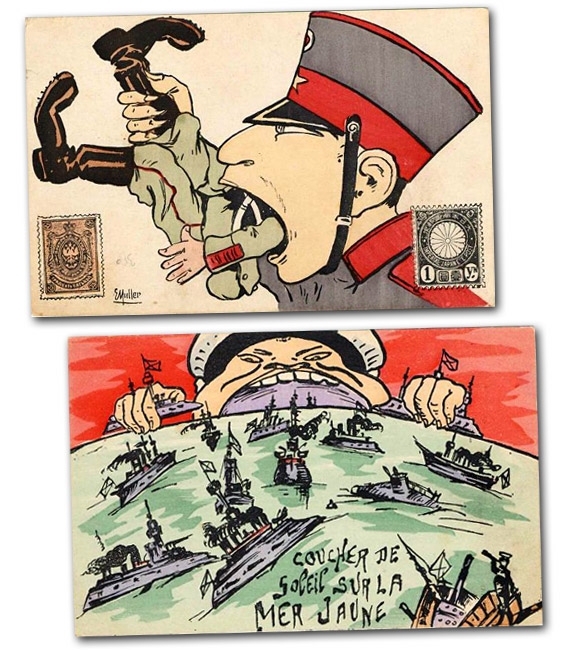

Visceral imagery of Japan swallowing the Russians—or, as will be seen, disgorging the yellow hordes of Asia from its maw—was also popular. An extended and usually balanced postcard series by “E. Muller” that features postage stamps from Russia and/or Japan on almost every individual graphic ends with the alarming image of the huge head of a Japanese soldier eating a uniformed Russian (the clinching Yellow Peril touch here is the Japanese soldier’s long, pointed fingernails). A crude French rendering captioned “Sunset on the Yellow Sea” sets the huge slant-eyed, buck-toothed head of a Japanese sailor on the horizon, mouth agape as if about to swallow the entire Russian fleet. (The sea’s name itself only enhances the message.)

|

|

These grotesque renderings of Japan’s insatiable appetite include almost reflexive little features associated with anti-Oriental racism—the sinister fingernails, for example (top), and the demeaning slanted eyes and buck teeth (bottom). Even the title of the second graphic—“Sunset on the Yellow Sea”—carries These grotesque renderings of Japan’s insatiable appetite include almost reflexive little features associated with anti-Oriental racism—the sinister fingernails, for example (top), and the demeaning slanted eyes and buck teeth (bottom). Even the title of the second graphic—“Sunset on the Yellow Sea”—carries

Yellow Peril overtones.

“Japanese Soldier Swallowing Russian Soldier”

[2002.4058]

“Sunset on the Yellow Sea”

[2002.6832]

|

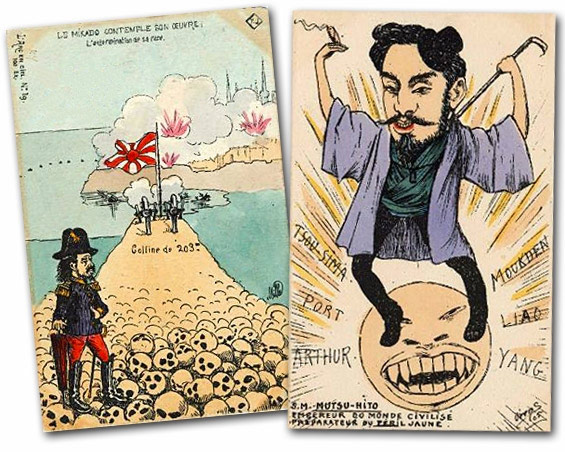

When the Meiji emperor (“Mutsuhito”) was separated from his imperial counterpart Nicholas II, foreign artists were free to paint the scene yellow. Thus, in a postcard titled “The Mikado Contemplates His Work,” the emperor stands on a highway of yellow skulls stretching across the sea to the distant battlefields. In another French graphic, the emperor appears to be leaping in the air in front of a yellow sun (it has slant-eyes and sharp buck teeth). The place names of Japanese victories emanate from this sun like rays (Mukden, Liaoyang, Tsushima, Port Arthur). To make sure no one will miss the point, the artist has provided a caption reading “Mutsuhito—Emperor of the Civilized World, Facilitator of the Yellow Peril.”

|

|

In “The Mikado Contemplates His Work” (left), his work is not merely death but death colored yellow. This is made even more explicit in the cartoon on the right, which identifies Mutsuhito as “Emperor of the Civilized World, Facilitator of the Yellow Peril.” The rays of the slant-eyed and fanged yellow sun spell out the names of great war victories. In “The Mikado Contemplates His Work” (left), his work is not merely death but death colored yellow. This is made even more explicit in the cartoon on the right, which identifies Mutsuhito as “Emperor of the Civilized World, Facilitator of the Yellow Peril.” The rays of the slant-eyed and fanged yellow sun spell out the names of great war victories.

[2002.3800] [2002.6864]

|

Another rendering of the “Triumph of the Yellow,” almost out of control, offers a sword-wielding figure in a robe standing on a mound of bloody Russian corpses with a blood-red sun behind him. In this case, the figure could just as well be Chinese as Japanese; and, indeed, yet another foreign rendering in this vein explicitly turns the situation about to portray “The Chinese Menace,” with Japan suddenly—and certainly unexpectedly—metamorphosing into the defender of Russia and Europe by keeping China penned in.

|

![“The Yellow Triumph” Artist unknown [2002_3931] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts Boston](image/2002_3931_s7850_Copy.jpg) ![“Menacing China” Artist unknown [2002_6779] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts Boston](image/2002_6779_s7852_Copy.jpg) |

Some Yellow Peril graphics border on hysteria. In “Triumph of The Yellow” (left), the swordsman atop a mound of corpses could as easily be Chinese as Japanese. In “The Chinese Menace” (right), China clearly IS the great peril—peering over the Great Wall toward Russia and Europe while Japan (!) stands guard. Some Yellow Peril graphics border on hysteria. In “Triumph of The Yellow” (left), the swordsman atop a mound of corpses could as easily be Chinese as Japanese. In “The Chinese Menace” (right), China clearly IS the great peril—peering over the Great Wall toward Russia and Europe while Japan (!) stands guard.

[2002.3931] [2002.6779]

|

Historically, the rhetoric and visual representation of a “Yellow Peril” is usually traced to Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany in the late 1890s, following Japan’s victory in the Sino-Japanese War (the original German is Gelbe Gefahr). In practice, the Western bogey of an Asia menacing the security and well-being of Europe dates back to much earlier times—to the Mongol “hordes” that did indeed sweep over vast swathes of territory in the 13th and 14th centuries, and to later visions of China as a “sleeping giant” that, if awakened, could imperil all Europe. What held China down was its failure to acquire the science and technology that lay behind the West’s industrialization and global expansion.

Japan’s crushing victory over China in 1895 signaled that a turning point in the global balance of power had come about in two ways. Unexpectedly, Japan rather than gigantic China had emerged as the dominant power in Asia. And it had done so by becoming “Western” and “modern” through mastery, among other things, of military technology. The ominous horde was still yellow, however: it was difficult for Westerners to distinguish one Oriental from another, and what the Japanese and their racial brethren would do with their burgeoning power in the future was unknowable.

Exit China, Enter Japan—in the final analysis, this was a distinction without fundamental difference to foreigners who simply feared the rise of Asia in general. “Color” mattered as much or more than nationality, and commercial artists who turned attention to these matters almost always made yellow the overwhelmingly dominant color in their palette.

|

![“Russian Anxiety” Artist unknown [2002_5142] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts Boston](image/2002_5142_s7856_Copy.jpg) |

“Russian

Anxiety”

[2002.5142]

|

The prevailing color of this graphic is the Yellow Peril giveaway, as stalwart Russia

towers over an absurd, archaic Chinese figure and a menacing little Japan. The prevailing color of this graphic is the Yellow Peril giveaway, as stalwart Russia

towers over an absurd, archaic Chinese figure and a menacing little Japan.

|

Even as Japan demonstrated its mastery of modern warfare, moreover—and even while many foreign commercial artists were indeed portraying Japanese leaders as “mirror images” to their Western counterparts—the abiding image remained that of a society that had not, in fact, really modernized fundamentally at all. Thus, in “Make Way for the Yellow,” which depicted Japan running over and trampling on the Europeans, the prolific postcard artist Mille fell back on the old pre-industrial clichés. “Japan” was a coolie pulling a rickshaw (and wearing a yellow haori coat), but while the rickshaw man was careless and irresponsible, his passenger was the other side of the Oriental coin—female, exotic, desirable in her traditional non-assertiveness.

|

“Make

Way for

the Yellows”

[2002.3799]

|

![“Make Way for the Yellows” Artist unknown [2002_3799] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts Boston](image/2002_3799_s7862_Copy.jpg) |

This French rendering of “Make Way for the Yellows” mixes various aspects of the most familiar Western stereotypes of Japan—the feminine and exotic (the comely passenger in the rickshaw); the backward and undeveloped (the rickshaw puller); and the threat of Japanese imperialism (the run-over or imperilled four great nations of Europe—Russia, Britain, France, and Germany). This French rendering of “Make Way for the Yellows” mixes various aspects of the most familiar Western stereotypes of Japan—the feminine and exotic (the comely passenger in the rickshaw); the backward and undeveloped (the rickshaw puller); and the threat of Japanese imperialism (the run-over or imperilled four great nations of Europe—Russia, Britain, France, and Germany).

|

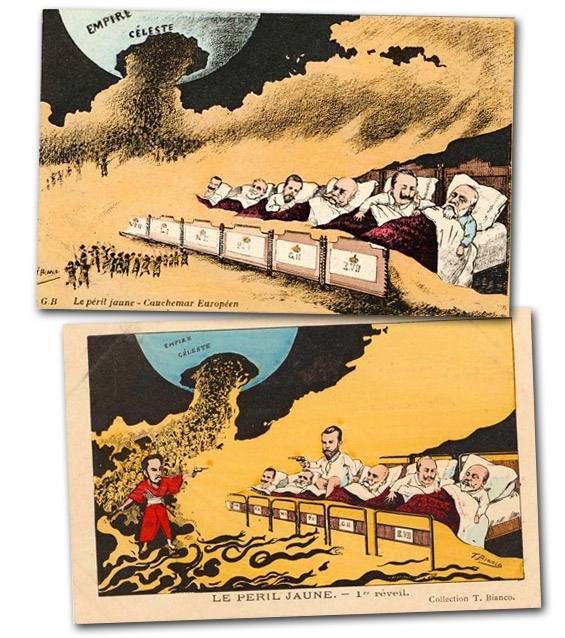

In this milieu, Japan’s ability to take on white, Christian, “Western” Russia and bring it to its knees did not merely mark the nation’s ambiguous emergence as a modern power—although it certainly did do this. It also signaled Japan’s emergence as leader of the masses of Asia, who so greatly outnumbered the collective population of the West. This was “Europe’s nightmare,” and artists and writers did not hesitate to bring it to the light of day. Bianco, for example, nailed this with typical incisiveness in a striking two-postcard set titled, respectively, “Yellow Peril—the European Nightmare” and “Yellow Peril—the Awakening.” In the nightmare graphic, Western leaders sleep in their beds while the “Celestial Empire” cracks open and pours out its yellow hordes. In “the Awakening,” the Japanese emperor has materialized to lead these hordes, and only the tsar has awakened to challenge him. They point pistols at each other, as serpents at the emperor’s feet crawl toward the Europeans. In both graphics the color, as usual, is overwhelmingly yellow.

|

|

In this stark two-card sequence by T. Bianco, titled “Yellow Peril,” the first illustration depicts “The European Nightmare.” Here the national leaders of Europe lie asleep, tormented by dreams of a flood of yellow people spilling out of China, the so-called Celestial Empire. In the second graphic, titled “the Awakening,” Japan (the emperor) has suddenly assumed lead of the yellow horde; the horde is closer than ever, even turned into serpents at the foot of Europe’s beds; and only the tsar has awakened to take on the Japan-led menace. In this stark two-card sequence by T. Bianco, titled “Yellow Peril,” the first illustration depicts “The European Nightmare.” Here the national leaders of Europe lie asleep, tormented by dreams of a flood of yellow people spilling out of China, the so-called Celestial Empire. In the second graphic, titled “the Awakening,” Japan (the emperor) has suddenly assumed lead of the yellow horde; the horde is closer than ever, even turned into serpents at the foot of Europe’s beds; and only the tsar has awakened to take on the Japan-led menace.

[2002.6815] [2002.6816]

|

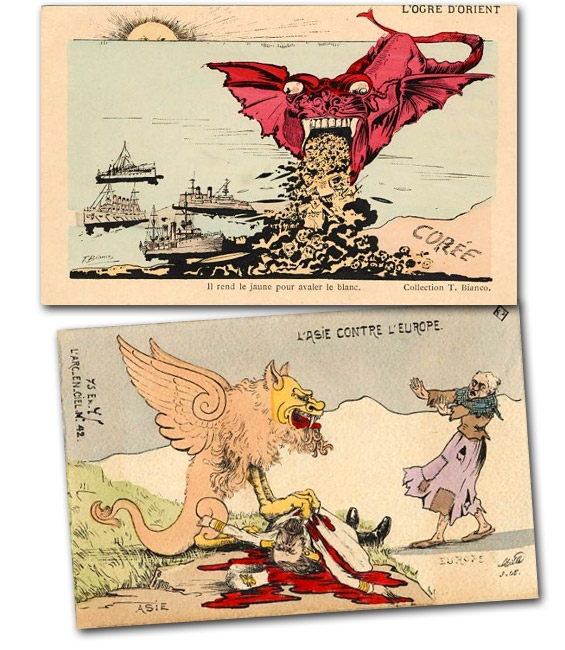

This alarming imagery slipped easily and naturally into Yellow Peril responses to the Russo-Japanese War that left out specific reference to Japan or the Japanese per se. Bianco, for example, also offered an “Ogre of the Orient” that resembled some sort of dragon with huge fins and a lion’s head. This monster was disgorging yellow masses into Korea, above a legend reading “He vomits the yellow to swallow the white (Il rend le jaune pour avaler le blanc).” Another French rendering, titled simply “Asia against Europe,” turned the Asian menace into a mythic chimera-like creature (with wings, a lion’s head, furry body, serpent’s tail, and the feet of a bird of prey). The bloodied corpse of Russia lay beneath its talons, while “Europe” trembled before the forbidding creature in the shocking form of a feeble old woman in ragged clothes.

|

|

Ultimately, the spectre of the Yellow Peril transcended Japan or China per se. It was a racist concept—an umbrella that indiscriminately covered the entirety of “Asia” or “the Orient.” In “The Ogre of the Orient” (top), the Yellow Peril is rendered as a particularly grotesque dragon vomiting the dregs of a yellow horde from Japan onto Korea and the Asian mainland. The monster “vomits the yellow to swallow the white.” In “Asia against Europe” (bottom), the yellow menace that has already killed off Russia takes the rather original form of a mythic chimera (a polyglot fire-breathing female creature), while Europe interestingly is portrayed as a weak old woman. Ultimately, the spectre of the Yellow Peril transcended Japan or China per se. It was a racist concept—an umbrella that indiscriminately covered the entirety of “Asia” or “the Orient.” In “The Ogre of the Orient” (top), the Yellow Peril is rendered as a particularly grotesque dragon vomiting the dregs of a yellow horde from Japan onto Korea and the Asian mainland. The monster “vomits the yellow to swallow the white.” In “Asia against Europe” (bottom), the yellow menace that has already killed off Russia takes the rather original form of a mythic chimera (a polyglot fire-breathing female creature), while Europe interestingly is portrayed as a weak old woman.

[2002.6812] [2002.3797]

|

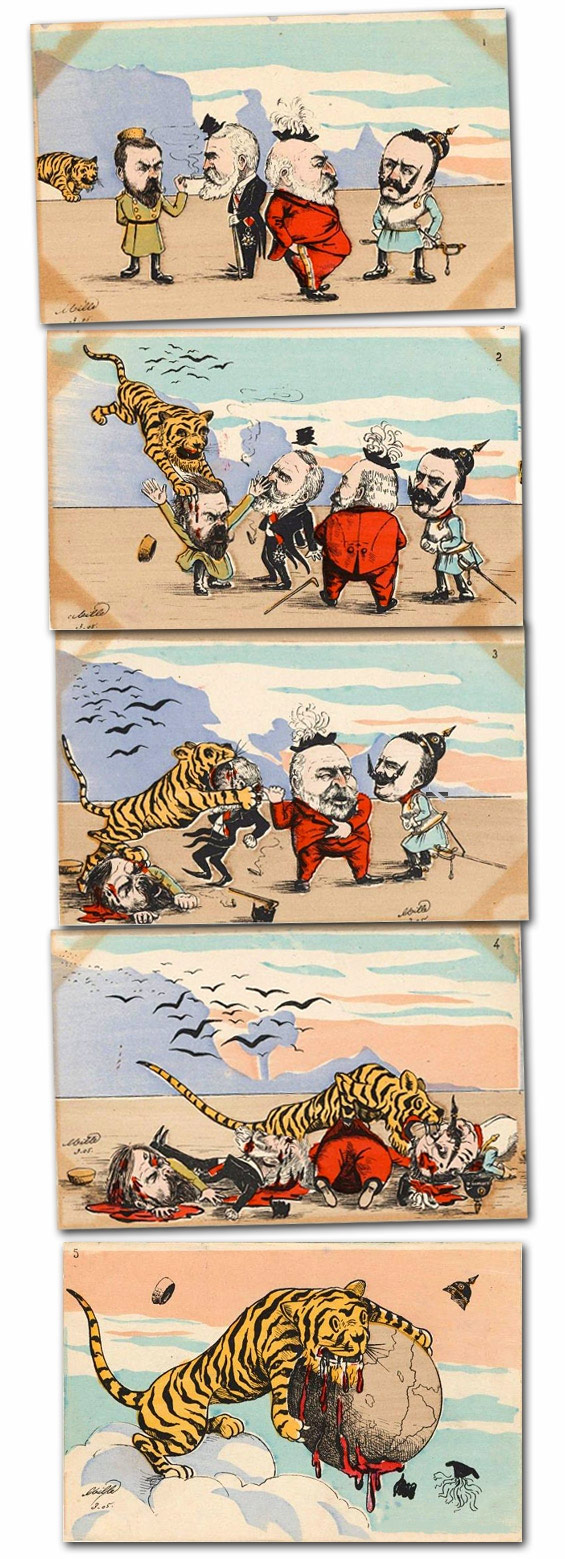

The most stunning Yellow Peril sequence that has come down to us is a five-card postcard set by Mille that carries no text whatsoever. The Asian menace takes the form of a realistic tiger. The four great powers of Europe (Russia, France, England, and Germany), represented by their easily recognizable leaders, are naively unaware of the approaching danger as they appear in the first illustration in the series. The tiger pounces—and after killing off Russia takes down the other three powers in turn. Metaphorically, a subhuman force is destroying the fully human representatives of Western civilization. And, indeed, in the fifth graphic there are no humans left—only the tiger, blood dripping from its jowls, embracing the entire globe in its claws.

|

|

This stunning five-card sequence, as vivid as a comic strip, begins with the leaders of the great powers of Europe (Russia, France, Britain, and Germany) standing together unaware of the approaching menace: a tiger representing Japan, or the Yellow Peril more generally. The tiger then devours Russia and France in turn, to the naive amusement of Britain and Germany who are next on the menu. The sequence concludes with the insatiable yellow tiger taking on the whole world. This stunning five-card sequence, as vivid as a comic strip, begins with the leaders of the great powers of Europe (Russia, France, Britain, and Germany) standing together unaware of the approaching menace: a tiger representing Japan, or the Yellow Peril more generally. The tiger then devours Russia and France in turn, to the naive amusement of Britain and Germany who are next on the menu. The sequence concludes with the insatiable yellow tiger taking on the whole world.

[2002.4118] [2002.4119] [2002.4120] [2002.4121] [2002.6792]

|

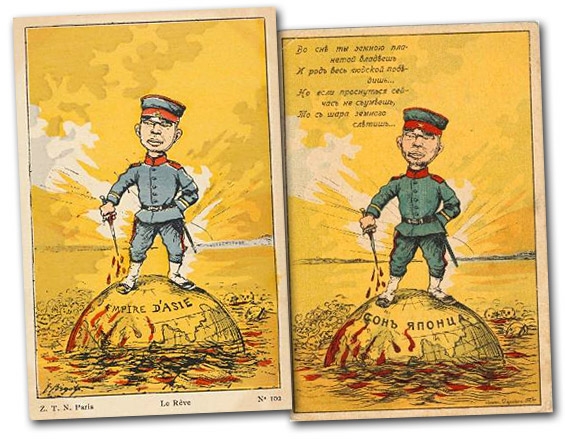

Bigot, the French cartoonist who had lived in Japan and at one early point in the war happily envisioned the Russians devouring their Japanese adversary, did not let his ineptitude as a prognosticator dampen his animus. On the contrary, he went on to produce an alarming image of a triumphant Japan that is almost impossible to forget. A Japanese soldier stands atop a globe floating in a blood-stained sea, a bloody dagger in his hand, the entire graphic saturated in yellow. Unsurprisingly, the Russians found this worth issuing as a postcard statement of their own.

|

|

In this almost psychotic rendering of Yellow Peril xenophobia by Georges Bigot, a Japanese soldier stands astride a globe saturated in yellow and red—the colors of race and blood that traumatized much of the Western world as it beheld Japan’s emergence as an imperialist power. In this almost psychotic rendering of Yellow Peril xenophobia by Georges Bigot, a Japanese soldier stands astride a globe saturated in yellow and red—the colors of race and blood that traumatized much of the Western world as it beheld Japan’s emergence as an imperialist power.

“The Asian Empire,” French version (left)

[2002.3727]

“The Asian Empire,” Russian version (right)

[2002.3726]

|

|

|