| |

CELEBRATING REBIRTH

Koizumi’s Tokyo was above all a celebration of rebirth after a catastrophic natural disaster. This was true also of the parallel series by his eight compatriots. Accelerated industrialization was integral to this rebirth, incorporating iron and steel to create a modern city of Western-style buildings and massive infrastructure that went beyond anything imagined before the earthquake.

|

|

|

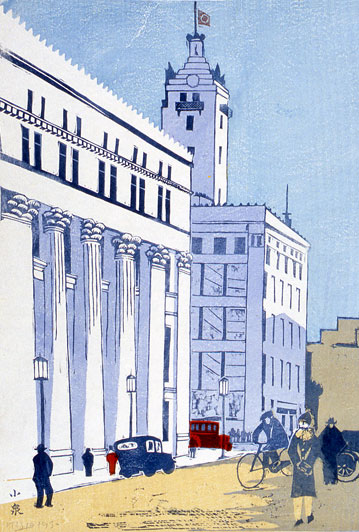

“Mitsui Bank & “Mitsui Bank &

Mitsukoshi Department Store (#03),” April 1930

Tokyo's reconstruction as an international city is expressed by the Mitsui Bank’s classical colonnaded façade, designed by a New York architectural firm. Although Mitsukoshi Department Store (right) withstood the earthquake, it was reconstructed by 1927, with modifications continuing through 1934. |

| |

Steel bridges, elevated highways, oil-storage tanks, a sprawling subway system, and proliferation of coal-powered trains and electric trams were all part of the new Tokyo.

|

|

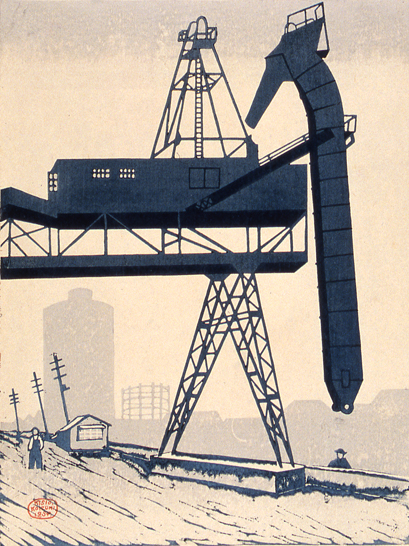

“Senju Town with Storage Tanks (#04),” June 1929

The starkly modern feel of this rendering of oil storage tanks prompted

Koizumi to note that this print “was well received and its ‘left wing’ style

was a source of comment.”

|

|

“Drawbridge at Shibaura

(#06),” September 1930 |

“Suehiro Street in Senju

(#96),” August 1937 |

|

|

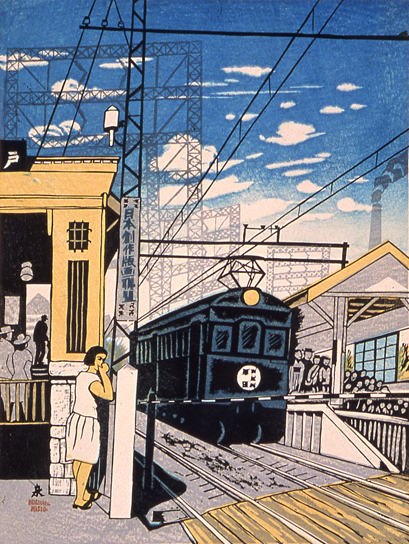

“Togoshi Ginza Station “Togoshi Ginza Station

(#27-revised),”

July 1940

New railway lines connected the suburbs to the commercial center in downtown Tokyo. The signboard promotes the Japan Creative Print Association, with which Koizumi was affiliated. |

“View of Sunamachi

[Jōtō Ward] (#54),”

July 1934 |

|

|

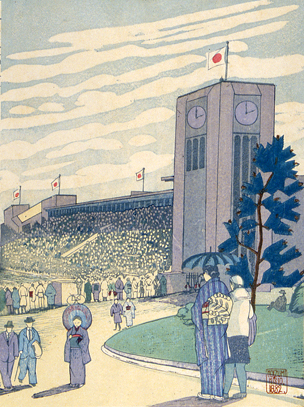

So were expansive parks and stadiums—the land often bestowed from estates of great wealth. Such public places amounted to recognition of the need for generous spacing in a cramped city, as well as a practical need for firebreaks. Quite possibly, they also reflected official concern with forestalling civil unrest. At least one rationale for the creation of the parks was to achieve more egalitarian dispensation of grand urban spaces.

|

“May Sports Season at Meiji Shrine

Outer Gardens (#27),”

May 1932

|

| |

At the same time, celebrating “new Tokyo” also involved celebration of lively cultural forms associated with being modern and up-to-date. The new above-ground and below-ground public transportation system, for example, stimulated the emergence of what amounted to virtual mini-cities at key terminals such as Shinjuku, Shibuya, Ueno, and the great “Tokyo station” itself. Huge department stores combined Western influences with attractive features from Japan’s own rich commercial tradition to become little cultural sites in and of themselves—complete with restaurants and exhibition halls. A “café culture” flourished, alongside drinking places, movie theaters, cabarets, and dance halls.

|

|

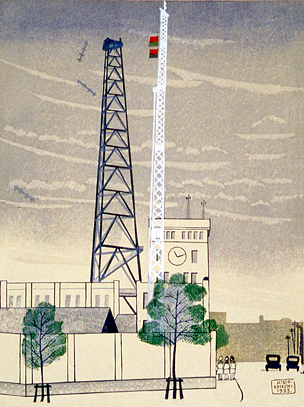

Certain of Koizumi’s images celebrated earlier markers of modernization, such as the Central Meteorological Observatory that withstood the earthquake. In this case his print, issued ten years after the catastrophe, was a homage to survival and resilience as well as renewal. Other images convey an almost charming comfort with diverse aspects of “the modern.” |  |

“Central Meteorological

Observatory (#41),”

September 1933

May 1932

|

| |

The Imperial Hotel famously designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, which also survived the earthquake, is festively decorated, somehow suggesting that such an expansive international perspective ensures continued survival.

|

|

“Entrance of the Imperial Hotel (#83),” October 1936 June 1929 “Entrance of the Imperial Hotel (#83),” October 1936 June 1929

The Imperial Hotel, designed by the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, was constructed between 1916 and 1923 and survived the earthquake with minor but not disastrous damage. As Koizumi observed, the hotel served “an international and cosmopolitan clientele as well as being a social club for the elite.” It was demolished and replaced in 1968.

|

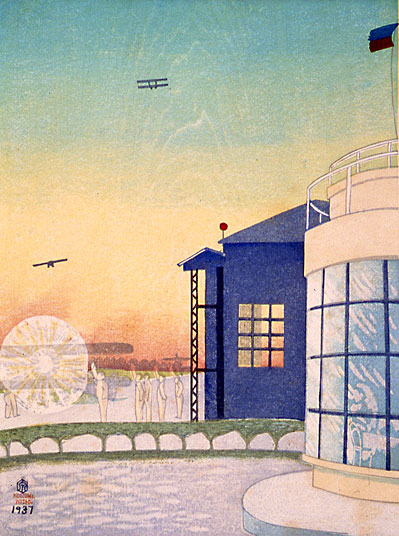

“Tokyo International Airport at Haneda (#87),” “Tokyo International Airport at Haneda (#87),”

March 1937

Although the first powered air flight in Japan took place in 1910, regular mail and commercial flights did not begin until the mid–1920s. The airport at Haneda was completed in 1932. By 1935, Japan had 235 planes in civil aviation, providing regular service to Korea, China, Taiwan, and Manchoukuo, as well as domestic flights. |

|

|

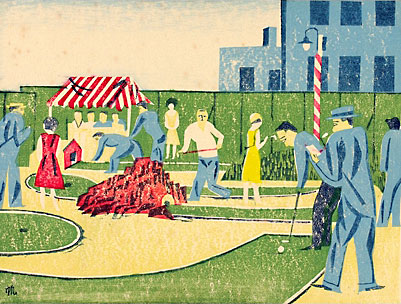

Golf, the quintessential Anglophile sport, is viewed from under the eave of a traditional Japanese building... |

“Golf Course at

Komazawa (#82),”

September 1936

May 1932

|

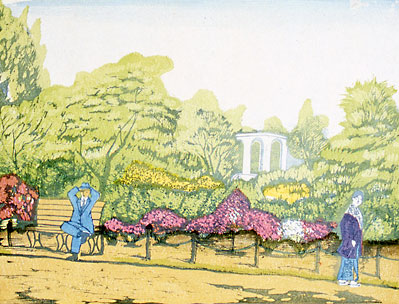

Public parks replace the scars of earthquake devastation. |   |

“Hibiya Park with Fresh

Leaves and Azalea

Blossoms (#05),”

July 1930 |

|

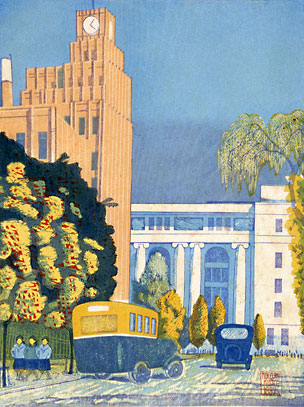

Imposing houses of finance, thoroughly modern and even neoclassical, are softened by lush greenery, strolling schoolgirls, and the putter of automobiles. |

“Municipal Hall and

Kangyō Bank (#35),”

October 1932

|

| |

Over and over, Koizumi dwells with affection on the city at night, including the Ginza glittering with neon lights. This is Koizumi’s celebratory trajectory: a city almost indistinguishable from any other great world metropolis. In many of the prints, hints at locality come only in the form of the occasional kimono-clad figure, or a sign in Japanese.

|

|

“Night View of Ginza in the Spring (#12),” March 1931 “Night View of Ginza in the Spring (#12),” March 1931

The 1923 earthquake completely leveled the Ginza's shops, department stores, restaurants, and cafés. By 1930, the district was entirely rebuilt, doubling its pre–1923 size. The brightly lit electric advertising signs and the headlights of motorized streetcars and automobiles pierce the darkness, proclaiming the city's progress.

|

| |

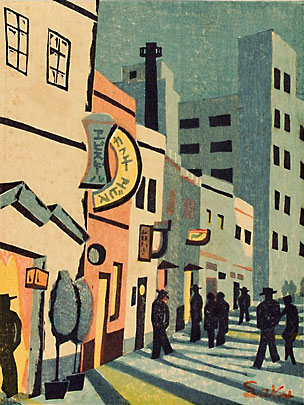

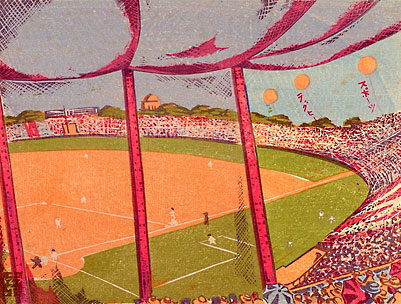

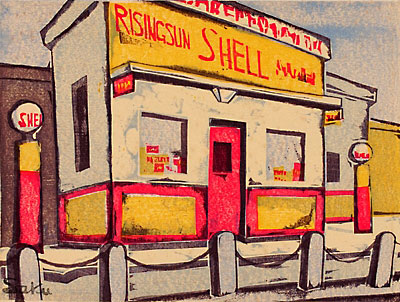

Some of the eight artists who contributed to the “100 Views of New Tokyo” subscription series were even more attracted to the modernity of post-earthquake Tokyo at the level of popular culture. Like Koizumi, they peopled their scenes with urban residents dressed in both Western and more traditional clothing. This was, indeed, one of the signs of a comfortable hybrid lifestyle. At the same time, Koizumi’s compatriots also were attracted to subjects that he himself, for whatever reasons, did not choose to celebrate. These included miniature golf, a “Shell” gas station, cafés, and a truly garish and expressionist Ginza crowd scene—as well as the interiors of a movie theater, dance hall, and “casino follies” revue. Viewed together with Koizumi’s series as a celebration of the reborn metropolis, there is an overall sense of great variety, vibrancy, and urban esprit.

|

|

“100 Views of New Tokyo,”1928-32, by 8 Artists

|

|

Some of the eight artists who contributed to the “100 Views of New Tokyo” subscription series were even more attracted to the modernity of post-earthquake Tokyo at the level of popular culture. Like Koizumi, they peopled their scenes with urban residents dressed in both Western and more traditional clothing. This was, indeed, one of the signs of a comfortable hybrid lifestyle. Some of the eight artists who contributed to the “100 Views of New Tokyo” subscription series were even more attracted to the modernity of post-earthquake Tokyo at the level of popular culture. Like Koizumi, they peopled their scenes with urban residents dressed in both Western and more traditional clothing. This was, indeed, one of the signs of a comfortable hybrid lifestyle.

“Cafe District in Shinjuku (#83),”

10/1/1930,

by Fukazawa Sakuichi |

“Miniature Golf (#10),”

9/1/1931,

by Maekawa Senpan |

|

|

“Subway (#11),”

1931,

by Maekawa Senpan |

“Meiji Baseball

Stadium (#86),”

12/1/1931,

by Fukazawa Sakuichi |

|

|

“Rising Sun Shell,

Showa Street (#84),”

6/1/1930,

by Fukazawa Sakuichi |

“Movie Theater (#29),”

12/1/1929,

by Onchi Koshiro |

|

| “Ginza (#65),”

8/7/1929,

by Kawakami Sumio |

Images courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art

|

|

At the same time, Koizumi’s solitary control over his “100 Views” enabled him to linger longer than his compatriots over what was familiar, traditional, and old. His pathways or wanderings to so many places over so many years thus also give loving attention to the seasons and the soothing presence of water (rivers, ponds, and canals), for example, as well as to Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, and traditional folk festivals. As it turned out, thirty-four of the sites he commemorated matched or approximated places celebrated in Hiroshige’s classic 1850’s treatment of Edo. Old and new commingled, and nostalgia went hand-in-hand with the powerful pull of modernity. Even while celebrating rebirth and the throbbing pulse of ever accelerating urbanization, Koizumi sought out and discovered quietude.

He also, as closer scrutiny of his series reveals, uncovered more unsettling undercurrents. One was urban sprawl and the emergence of suburbs that often obliterated attractive vestiges of the past. Another was imbedded in the very celebration of industrialization and modern infrastructures—for oil tanks, steel constructions, and the like were an everyday reminder of the nation’s dependence on foreign resources. The period from 1928 to 1940 when Koizumi produced these prints coincided with the years that the nation’s increasing dependence on overseas markets and raw materials resulted in heightened international tensions and, ultimately, militarism and war.

|

|

| |

|

|

|