| |

RECASTING “NATIVES”

Dean Worcester’s images of the Philippines circulated widely in the United States, from the halls of Capitol Hill in Washington to the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904 to the parlors of middle-class Americans. As they circulated, the images changed—and even when they didn’t, the changing contexts of their presentation told new stories about the American colonial experience. Photographic images moved from the darkroom to the printed pages of official state documents, most notably with the publication in 1905 of the Census of the Philippine Islands. Here the surveillance powers of the state that had been so crucial in pacifying the islands now joined with the documenting, collecting, and classifying impulses of the anthropological gaze.

|

|

| |

The Career of an Image

Tracing one photographic encounter as it moved from Dean Worcester’s field work to its other public uses shows how the uneasy but necessary intimacy of the colonial encounter was frequently stripped away by the time images circulated back to the metropole and were put to other political uses.

|

|

| |

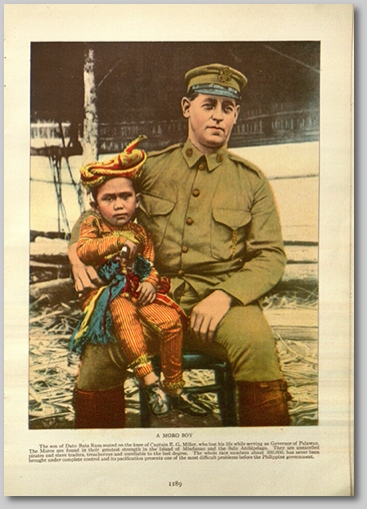

In this 1905 photograph, E. Y. Miller, an officer in the U.S. Army and the colonial governor of the Palawan province, holds on his lap a Moro child. The boy was the son of Datu Batarosa, a powerful local chief with whom Miller would have worked on a regular basis.

Worcester’s caption: “Moro boy, type 1. Son of Datu Batarasa,

with Governor E. Y. Miller,” 1905. Location: Bona-Bona, Palawan

[dw23A003]

|

|

|

A photo of the same boy with other children in the background creates a different impression.

Worcester’s caption: “Moro boy, type 1. Son of Datu Batarasa. Full length front view,” 1905

Location: Bona-Bona, Palawan

[dw23A001] |

| |

Miller drowned in 1910, and Worcester’s annual report as secretary of the interior reproduced this image as its frontispiece, noting that the “provincial service and the work for the non-Christian inhabitants of Palawan have suffered an irreparable loss.” Worcester’s image of Lieutenant Miller extended one man’s benevolence to that of the entire American colonial undertaking.

Title page and frontispiece, Ninth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior to the Philippine Commission for the Fiscal Year Ended July 30, 1910 (Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1910).

[Sec_Int_1910]

|

|

|

In November 1913, National Geographic featured a hand-colored version of the photo. The caption focuses on the Moros, describing them as “treacherous and unreliable” and stresses the need to bring them under control.

By now, Captain Miller’s photograph has begun to tell a new story, much less personal, more simplified, and far out of Dean Worcester’s power to control.

|

| |

National Geographic caption: “A MORO BOY. The son of Dato Bata Rosa seated on the knee of Captain E. G. Miller [sic], who lost his life while serving as Governor of Palawan. The Moros are found in their greatest strength in the Island of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago. They are unexcelled pirates and slave traders, treacherous and unreliable to the last degree. The whole race numbers about 300,000, has never been brought under complete control and its pacification presents one of the most difficult problems before the Philippine government.”

[ng1189_1913_Nov_27]

|

|

| |

Worcester as Storyteller

Like most colonial officials, Worcester returned regularly to the United States. By 1913, he had hired a booking agent who arranged paid lectures across the country. During his two-year tour, Worcester’s images reappeared as lantern slides (sometimes hand-colored), projected in public auditoriums as a backdrop to Worcester’s own booming voice that spoke with great authority about the colonial project. In December 1913 and January 1914, Worcester packed Carnegie Hall with a series of lectures on such topics as “The Picturesque Philippines” and “Wild Tribes of the Philippines.” The New York Times praised the lectures for including both photographs and films: Each picture told a story of the marvelous progress made by Americans in teaching civilization to the savage tribes of the Philippines…. The savage, naked, dirty, and unkempt, was shown in still photographs, while that same one-time savage, clothed, intelligent in appearance, and clean, later was shown in moving pictures. [1]

Worcester’s visual extravaganza wowed not only the crowds at his lectures, but government officials as well. One of the final stops on Dean Worcester’s U.S. speaking tour was in Washington, D.C., where he appeared before the Senate Committee on the Philippines. His testimony was both oral and visual: on December 30, 1914, he lectured the senators for two hours in a darkened committee room illuminated by the glow of his lantern slides.

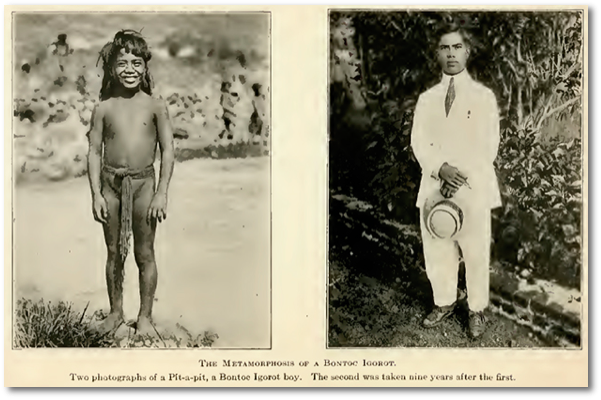

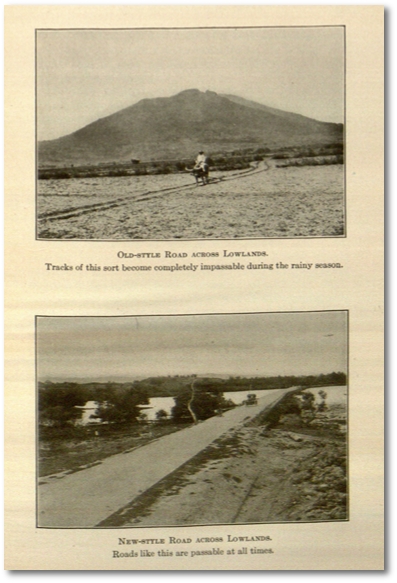

Old / New

As the photographs that Dean Worcester and others took in the Philippines were collected, sorted, and circulated throughout the United States, one style emerged as a visual habit that shows the power of photography as its anthropological aims were put to storytelling ends. Published works about the Philippines—by Dean Worcester or others—regularly featured images of transformation, both of the Philippine landscape and its inhabitants: a paved road replaces a meandering footpath; a modern schoolhouse stands next to a thatch-roofed hut; a long-haired boy returns as a white-suited man. The visual trope of sequential transformation was among the most popular ways of depicting America’s colonial enterprise, appearing in books, magazines, and even in official government reports.

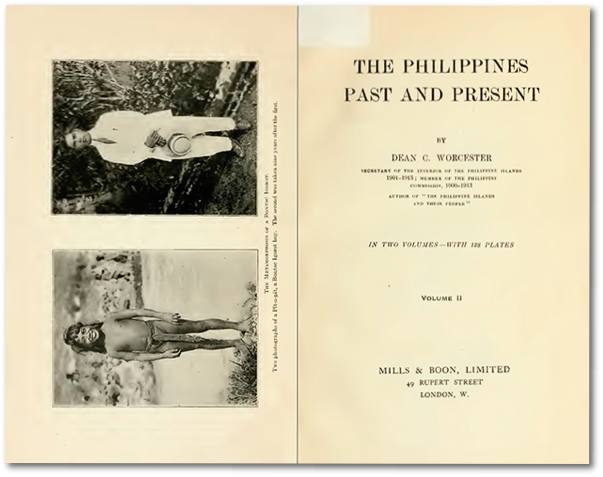

Putting images in a sequence creates a narrative—with a beginning, a middle, and an end. In an era that cherished progress, uplift, and evolution as keywords of civilization, photographic sequences told persuasive stories to Americans about the nation’s new imperial endeavors in the Philippines. Several can be found in Dean Worcester’s massive account of U.S. colonial policy, The Philippines: Past and Present, published in 1914 (below).

|

|

|

|

| |

The caption of the frontispiece to Worcester’s 1914 book reads:

“The Metamorphosis of a Bontoc Igorot. Two photographs of a Pit-a-pit, a Bontoc Igorot boy. The second was taken nine years after the first.”

The text explains that the man became a doctor. By including the contrasting images of a barefoot boy and a white-suited man as the first pictures in his book, Dean Worcester presented images as evidence of the achievements of the colonial project.

Title page and frontispiece, Dean C. Worcester,

The Philippines Past and Present (1914).

[1914_PhilPstPres_v2] [1914_PhilPstPres_v2_frontis]

|

|

Dean Worcester not only used images to document personal transformation, but also the remaking of the Philippine landscape. Roads, bridges, trains, and farm equipment appear in his photograph collection as signs of modernization.

captions:

top: “The Old Way of

Crossing a River.”

bottom: “The New Way of Crossing a River.”

Dean C. Worcester,

The Philippines Past

and Present (1914).

[dw_ppp_v2_006] |  |

captions:

top: “Old-style Road across Lowlands. Tracks of this sort become completely impassable during the rainy season.”

bottom: “New-style Road across Lowlands. Roads like this are passable at all times.”

Dean C. Worcester,

The Philippines Past

and Present (1914).

[dw_ppp_v2_004] |

|

| |

Bakidan

Bakidan was a Kalinga chief whom Worcester knew well from his travels in the mountains of Luzon. Over time, however, as Worcester published accounts of his time in the Philippines, descriptions of his relationship to Bakidan changed from depictions that highlighted close and personal relations to stories that erased Bakidan’s individuality and highlighted his tribal and “savage” identity.

|

|

|

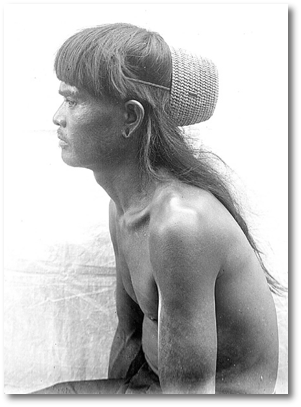

This photograph of Bakidan, a Kalinga chief, was taken in 1905 during an extended stay by Worcester in the village of Bunuan in the northern Philippines.

Worcester’s caption: “Kalinga man named Bakidan, type 1. Half length front view,” 1905

Location: Bunuan, Cagayan

[dw05a002]

|

Worcester reproduced this image of Bakidan in The Philippines Past and Present with a caption stating that he “saved the lives” of Worcester and others during their first trip to Kalinga country.

Book caption: “Bakidan. This Kalinga chief saved the lives of Colonel Blas Villamor, Mr. Samuel E. Kane, and the author during the first trip ever made through the Kalinga country by outsiders.”

[PPP_v1_Bakidan]

|  |

| |

Taken during his 1905 journey to Bunuan, this photograph shows Bakidan (highlighted in red) with three other chiefs, and, at the center, Worcester and Colonel Villamor. These four chiefs appear elsewhere in Worcester’s photographic collection, but not identified as chiefs or brothers.

Worcester’s caption: “Blas Villamor, Bakidan, Saking, and two other brothers of Bakidan, and myself. There are six brothers in this family and they rule the upper Nabuagan River valley. Bakidan is the most powerful,” 1905.

Location: Bunuan, Cagayan

[dw05A010]

|

|

| |

In his 1914 book, Worcester depicted his trip to the Kalinga as a journey “In Hostile Country” rather than a visit to a leading local politician. Worcester noted that “the four chiefs were not as yet ready to lay down their shields or head-axes.”

Book caption: “In Hostile Country. Colonel Villamor and the author at Bakidan’s place in the Kalinga country. The four chiefs were not as yet ready to lay down their shields or head-axes.”

[dw05A010]

|

|

| |

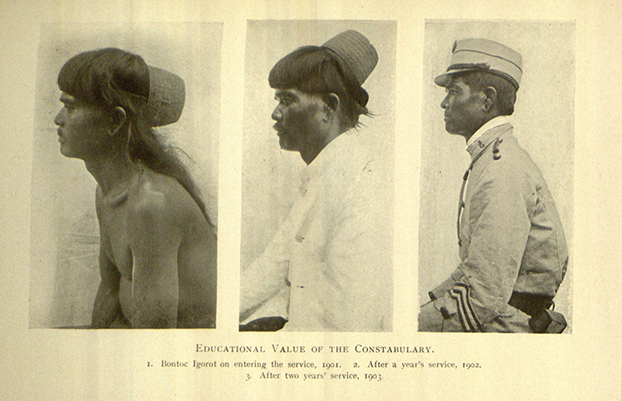

From Fact to Fiction

Sometimes the images in the Dean Worcester collection were simplified or altered by Worcester to serve his own political ends—he took them for political purposes, of course. But Worcester—a politician, anthropologist, scientist, and photographer—was unique. Sometimes images of Filipinos were used by other authors and publishers, many of whom had little connection to the Philippines and felt less compunction about playing fast and loose with the photographic record. Consider the following depiction of the “educational value of the constabulary,” published in Frederick Chamberlin’s The Philippine Problem, 1898–1913 (1913). |

|

|

| |

This sequence of photographs was published in the 1910s both in a government report and a popular account of U.S. Philippine policy. At first glance, the series appears to tell a story of benevolent colonialism by tracing the transformation of a soldier after “a year in jail.” But the photographic archive suggests a more complicated history.

Illustration in Frederick Chamberlin, The Philippine Problem, 1898–1913 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1913).

Book caption: “Educational Value of the Constabulary. 1. Bontoc Igorot on entering the service, 1901. 2. After a year’s service, 1902. 3. After two years’ service, 1903.”

[Chamberlin_Feb_03_000005_EdConst]

|

|

| |

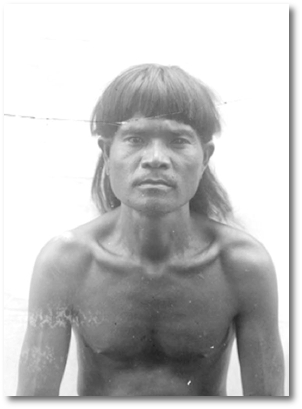

This sequence was a famous image of U.S. colonialism in the Philippines, depicted in government documents and popular publications. But when we trace the narrative back from the printed page to the moment of photographic encounter, the story gets more complicated. Worcester’s notes and archives tell a different story of transformation, in which he took four different photographs in 1901, and only arranged them much later in a sequence with a narrative of colonial uplift. |

|

Worcester’s notes show that the first photograph in the reprinted sequence was taken in February 1901 in Manila, and that Worcester had gone out of his way to recruit sitters. “Took the Igorrotes home, fed them up and photographed them,” he noted on February 6. [2] |

|

Worcester’s caption:

“Bontoc Igorot man, type 5.

Half length profile view,” 1901.

Location: Manila, Manila

[dw08A026] |

The second photograph of the sequence—along with the one shown below—were both taken in Manila in June 1901, and thus could not have reflected “a year’s service” in the Philippine Constabulary, as the series caption claimed. |

|

Worcester’s caption:

“Bontoc Igorot man, type 5.

2/3 length profile view,” 1901.

Location: Manila, Manila

[dw08A028] |

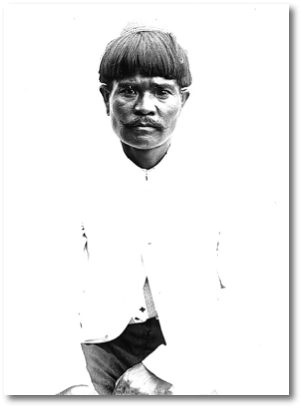

The front view of this man, clearly taken at the same time as the middle picture above, allows his face to be seen. |

|

Worcester’s caption:

“Bontoc Igorot man, type 5.

Half length front view,” 1901.

Location: Manila, Manila

[dw08A027] |

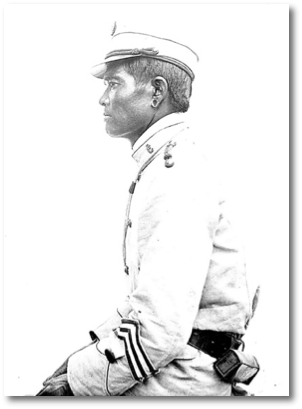

It is unclear when or where the third photograph in the sequence was taken. It may have been taken in Manila in 1901 or in the highland province of Bontoc in 1903. While this appears to be Francisco, the same man depicted in the first of the three photographs of the sequence, it was not taken “after a year in jail,” as Worcester reported in published writings accompanying these images. |

|

Worcester’s caption:

“Bontoc Igorot man, type 5.

After a year in jail.

Half length profile view,” 1901.

Location: Bontoc, Bontoc

[dw08A029] |

In his diary for June 21, 1901, Worcester noted that “Francisco had on a full rig of cloths [sic]—white coat, trousers made out of a pair of miner’s Alaska drawers, army leggings and American shoes,” closely matching this image of a constabulary uniform (above). But in Manila that June, Worcester also photographed Francisco in a more “primitive” state (right). |

|

Worcester’s caption:

“Bontoc Igorot man, type 5.

Called Francisco.

Half length front view,” 1901.

Location: Manila

[dw08A025] |

| |

These images show the power of photographic manipulation, and cause us to ask why an author might have wanted to shuffle photographs in service of a good story. But they also make us wonder whether Dean Worcester was not so much a puppet-master but also entranced by his own narrative of colonial control and uplift. Evidence suggests that he only put the images into this narrative in a government report in 1910, but that he used the images quite often afterward, even in his congressional testimony in 1914, when he told Congress that “I will show you the evolution of the first Bontoc soldier who ever enlisted…. This man is a chief named ‘Francisco,’ dressed as he had been when I first saw him. [indicating] This slide shows how he looked a year after, after he had been in contact with the Americans.” [3] Colonial storytelling was a complicated matter that was never entirely under the storytellers’ control.

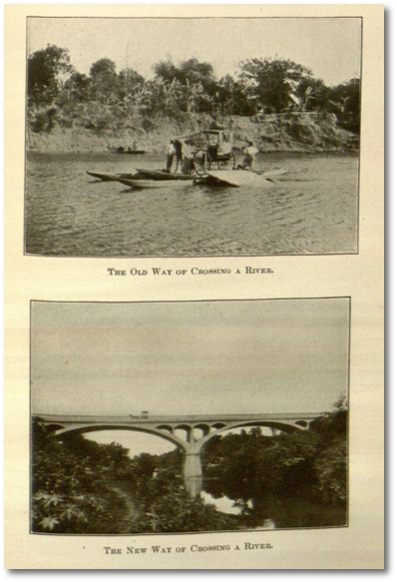

Recasting “Natives” for the National Geographic

The blend of the scientific and the touristic, the official and the private that marked colonial Philippine photography reached its apotheosis in the pages of National Geographic, the iconic magazine that brought the world to the parlors of Victorian America. Founded in 1888, the National Geographic Society initially found few readers for its dry and scholarly publications. But subscriptions to The National Geographic Magazine skyrocketed after the U.S. embarked on overseas colonization, and a revolution in printing technology enlivened the pages with photographs—many of them painstakingly tinted and reproduced in full color. Articles on the Philippines appeared with regularity after 1898—over 30 were published between 1898 and 1908—and photographs from Dean Worcester’s collection illustrated many of them.

The connections between Worcester’s entourage and the National Geographic Society were thick and deep: photographer Charles Martin, who appears often in Worcester Collection photographs (he took many of them as well) became head of the NGS Photographic Laboratory in 1915 after he left the U.S. Army.

In the pages of the magazine, Worcester shared his familiar stories of colonial uplift, and readers delighted at the array of images that illustrated his articles. His photographic essays were not without controversy, however; a 1903 article by another author that depicted bare-breasted Filipina women prompted debate among the magazine’s editors about its propriety. Worcester made a claim for the images’ scientific value, won the argument, and revolutionized the magazine’s editorial practices.

|

|

|

In November 1913,

In November 1913,

National Geographic juxtaposed the familiar and the exotic in an article by Dean Worcester, with a run of hand-colored photographic illustrations of rural Filipinos.

cover, The National Geographic Magazine, November 1913

[ng0001_Nov1913]

|

The title of Dean Worcester’s article:

“The Non-Christian Peoples of the Philippine Islands

With an Account of What Has Been Done for Them under American Rule”

The National Geographic Magazine, November 1913

[ng0002_Nov1913] |  |

| |

Thumbnails show the layout of the photographs selected and colorized for Worcester’s article.

The National Geographic Magazine, November 1913

[ng0002_Nov1913]

|

|

| |

Presenting “Peoples”

Through his text and images—carefully hand-colored by National Geographic staffers—Dean Worcester conveyed to a mass audience of American readers his sense of the racial landscape of the Philippines and boasted of “what has been done for them under American rule.” The images selected for his November 1913 National Geographic article introduced appealing figures representing tribes rather than individuals; vibrant colors accentuated the sense of the exotic for American readers.

|

|

| |

“A Mandaya Warrior” and “A Mandaya Woman”

[ng1170-1171_Nov1913]

|

|

| |

“Mangyans” (above) and “Ilongot Woman and Girls”

[ng1178-1179_Nov1913]

|

|

| |

“A Negrito” (top left); “A Tagakaolo” (top right)

“A Lubuagan Igorot Woman” (bottom two images)

[ng1180-1181_Nov1913]

|

|

| |

“Tiruray Women” (top)

“A Tingian Girl” (bottom left); “A Tingian Girl in Mourning” (bottom right)

[ng1184-1185_Nov1913]

|

|

| |

“An Ilongot Family” (left) and “Wild Tinglians of Apayao” (right)

[ng1186-1187_Nov1913]

|

|

| |

“A Tingian Man” (left) and “A Moro Boy” (right)

[ng1188-1189_Nov1913]

|

|

|