| |

Worcester’s caption: “Bontoc Igorots in automobile,” 1904. Location: Manila

[dw08A112] detail |

|

| |

COLONIAL COUNTERPOINT

The American colonial experience in the Philippines was full of contradictions, as officials sought simultaneously to control the Filipinos and to engage and uplift them. Dean Worcester cast himself as the nation’s leading expert on the Philippines, and took plenty of credit for that work: “not one single measure for their betterment has ever been proposed by anyone but myself,” he insisted in a letter to Secretary of War William Howard Taft in 1908. [1] Dean Worcester’s mixed motives appear in his photographic collection, which combined romance and condescension. Worcester’s official job as head of the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes was to defend indigenous Filipinos; he found himself committed to changing Filipinos’ ways of life even as he wished them to stay frozen in time. Ultimately, the only way he could imagine to protect them was to put them—and their culture—into a museum.

|

|

|

| |

In addition to taking photographic images, Worcester and his colleagues also recorded Filipino voices. But visual accounts of Filipinos using Western technologies—as in this image of a phonograph—often suggested the cultural inferiority of Filipinos.

Worcester’s caption: “Making a phonograph record. Group of Lubuagan men singing,” 1908. Location: Lubuagan, Bontoc

[dw08F021] detail

|

|

| |

Depictions of rural Filipinos encountering American colonial officials often showed Filipinos awed by western technology, juxtaposing two ways of life, one marked as advanced, the other as backward.

Book illustration and caption: “Entertaining the Kalingas. They are listening with great interest to the reproduction of a speech which one of their chiefs has just made into the receiving horn of a dictaphone.” from Dean C. Worcester, The Philippines Past and Present (New York: Macmillan, 1914), vol. 1, p. 464.

[PPP_v1_dictaphone]

|

|

| |

Through institutions such as schools, churches, workshops, and military training camps, American colonial officials sought to transform Filipinos. The institutions that aimed at uplifting Filipinos taught them not about their own culture, but that of the Americans: teaching English rather than Philippine languages, celebrating the Fourth of July rather than the outlawed Philippine national holidays, and decorating classrooms with portraits of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln.

|

|

| |

Colonial officials such as Dean Worcester boasted of the civilizing effect of American education. American flags decorate this classroom in the northeastern province of Isabela. Display of the Philippine flag had been outlawed a few years earlier.

Worcester’s caption: “Group of Ilocano and Gad-Dane school boys, with their American teachers,” 1905. Location: Echague, Isabela

[1898_AmAnthopologist_p300_p303]

|

|

| |

The colonial military was among the most transformative institutions. Its two main branches, the Philippine Scouts and Philippine Constabulary began as temporary military expedients during the Philippine-American War, as American officers sought to suppress the insurgency by recruiting men from some ethnic groups to fight as soldiers against others. But in the years after the war, colonial officials touted the value of the Scouts and the Constabulary as schools for citizenship. Frederick Chamberlin, an American journalist, wrote that “[n]ext to baseball, many are inclined to believe that the constabulary is the most active single civilizing agent in our administration.” [2]

|

|

|

|

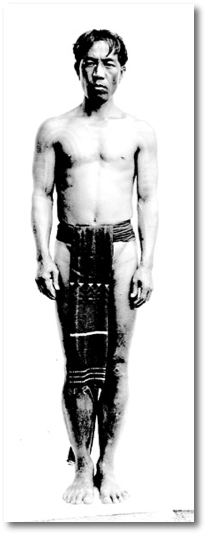

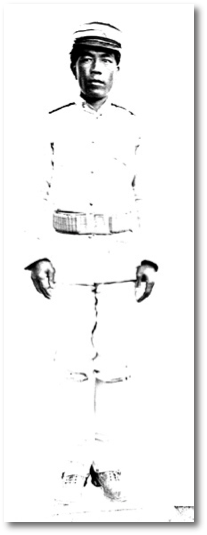

Images such as this pair of photographs—in which a Constabulary soldier is photographed “in uniform” and “without uniform”—helped Worcester show the transformation of tribal Filipinos through military service.

Far left: Worcester’s caption: “A Bontoc Igorot Constabulary soldier, without uniform.,” 1903.

Location: Bontoc, Bontoc

[dw08A055]

Left: Worcester’s caption: “A Bontoc Igorot Constabulary soldier in uniform.,” 1903.

Location: Bontoc, Bontoc

[dw08A054] |

Worcester believed the Philippine Constabulary was both a civilizing influence and a more cost-efficient way to run an army. This chart, in Worcester’s 1914 book The Philippines Past and Present, shows how the U.S. military relied on Filipino soldiers’ local knowledge, and also shows the discrepancy between their low salaries and those of the Americans.

[PPP_v1_constabulary_chart] |

|

| |

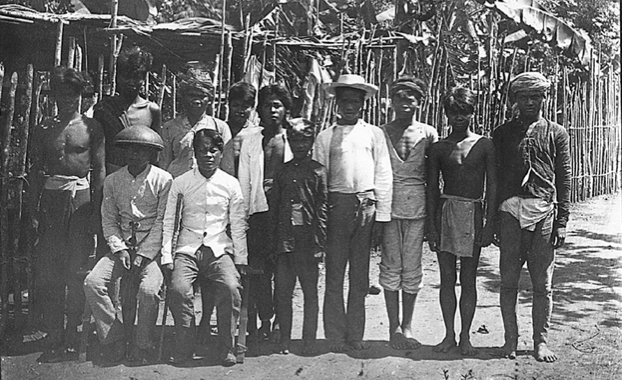

In the following series of three photographs, which Dean Worcester noted were evidence of the transformation of “old school” Igorot warriors into “new school” soldiers. He arranged photographs in specific ways to tell a story of colonial uplift. |

|

| |

Worcester identified this 1903 series “Bontoc Igorot warriors of the old school and new school.” Showing the men first in traditional dress with shields and spears, and then in U.S. military uniforms, the series boasts of the elimination of their traditional Filipino ways of life.

1903. Location: Bontoc

[dw08A051] [dw08A052] [dw08A053]

|

|

| |

As his tenure as a colonial administrator continued, Worcester traveled to remote regions of the Philippines on almost-yearly tours, but as he grew more comfortable in his government offices in Manila, his travels were shorter, more ritualized, attended by an ever-larger retinue of colonial officials, and restricted to ceremonial encounters with tribal chiefs. The photographic record reveals these visits less as cultural exchanges and close observations, but public spectacles. They were increasingly staged performances of a way of life that was already disappearing.

|

|

| |

Colonial officials went to great lengths to teach Filipinos Western athletic games, such as this foot race with an American flag (on left) at the finish line. At the same time, they suppressed Philippine popular sports.

Worcester’s caption: “Finish of the long distance run,” 1908.

Location: Quiangan, Nueva Vizcaya

[dw07A034] detail

|

|

| |

The traditions behind tribal cultures were suppressed, but the spectacle was not. This image of war games in the southern Sulu archipelago shows how U.S. officials such as Dean Worcester could look with approval on Filipino traditions, but only when they were confined to ceremonial performances.

Worcester’s caption: “Jolo Moros fencing with shield

and wooden barong,” 1901. Location: Jolo, Sulu

[dw23D023] detail

|

|

| |

Worcester went out of his way to document styles of dress. Even under Spanish rule, rural Filipinos moved between traditional and Western styles of dress. Anthropologist Albert Jenks noted that among the Tingian people, “[t]he men commonly wear only the breech-cloth, though they usually possess trousers and shirts which may be worn on festival occasions.” [3] Worcester noted in his diary that “most of the Igorrote headmen had coats of white or blue or other color (frequently a khaki coat they had got off a soldier) and some of them also wore trousers of remarkable patterns.” [4] Whether for soldiers or schoolchildren, clothing was a powerful marker of progress toward “civilization,” and the Dean Worcester collection documents the importance of clothing in a narrative of colonial uplift.

|

|

|

|

| |

Paired images such as these sought to use clothing as markers of cultural progress, favorably comparing “Sunday clothes” with “every-day clothes.” But sometimes images told different stories than the narratives of civilization in their captions. On closer examination, these men did not look very different in their Sunday dress than their everyday clothes.

Worcester’s caption: “Group of Tagbanua men in their Sunday clothes,” 1905

Worcester’s caption: “Group of Tagbanua men in their every-day clothes.”

[dw04B003] detail [dw04B004] detail

|

|

| |

During a 1909 tour of Bukidnon, a mountainous region in the southern island of Mindanao, Worcester was greeted by women who had clearly donned their finest clothing for the arrival of the colonial officer.

|

|

| |

By 1909, Dean Worcester’s visits to provincial capitals were carefully choreographed affairs. Women in the southern province of Bukidnon appear here in Western dresses to greet Worcester and his traveling party, and to show off their own mastery of the norms of Western cultural behavior.

Worcester’s caption: “Bukidnon women dancing in the street to welcome us,” 1909.

Location: Impalutao, Bukidnon

[dw11I006] detail

|

|

| |

But the women of Bukidnon had clearly learned that civilization required putting away their traditional clothes, even if they brought them out for special occasions “to show that they had them.” If the anthropological gaze sought to turn a “primitive” society into a laboratory in order to study it, sometimes it was too successful. Increasingly, traditional indigenous Philippine cultures were being turned into a museum—displaying clothes that people no longer wore.

|

|

| |

Even as Bukidnon women chose their clothes to please Worcester, they also knew of his interest in traditional Philippine cultures. These women displayed an older costume during his ceremonial visit, but did not wear it “lest they displease” the Americans.

Worcester’s caption: “One of the dummies at the foot of the arch shown in 11j003. The people were afraid to wear these clothes lest they displease us,

but wanted to show that they had them,” 1909.

Location: Kalasungay, Bukidnon

[dw11J004] detail

|

|

|