|

| |

THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL GAZE

Photography was a way of seeing the Philippines that emerged out of the political and military needs of the U.S. colonial government. As such, it was part of a constellation of governance techniques that included mapping, census taking, and cultural observation.

The photographs in the Worcester archive reflect the visual and cultural concerns of the emerging social science of anthropology, a field that initially took as its subject the study of so-called “primitive” societies. At the turn of the century, anthropology had emerged as a professional field of study; scholars formed the American Anthropological Association in 1902. But many of its practitioners were people like Dean Worcester, amateur scholars who sought to document, analyze, and classify cultures in regions of the world that were increasingly coming under colonial control.

Ethnography in the Philippines had begun in the 19th century as Spanish writer Pedro Paterno and German Ferdinand Blumentritt traveled to the region. But these works were almost completely unknown in the United States before 1898. In the Bureau of Science and the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes, founded in October 1901, Dean Worcester gave ethnographic study an official home, charged to “conduct systematic investigations” [1].

Early ethnographers’ methods ranged from observation and interviews to archaeological fieldwork, but in 1900 some of the most exciting new work in anthropology took advantage of the portability and ease of use of the hand-held camera. Within a year of its founding, the Bureau of Science had hired Charles Martin, Dean Worcester’s photographic assistant, as the first civilian “government photographer” in the Philippines.

Many of the images in the Worcester archive reflect a way of looking that is specific to visual anthropology. How does a photographer look at his subjects when trying to document a “race” or “tribe”? When an anthropologist looks through the camera lens, what does he or she see? The anthropological gaze is first and foremost an act of looking. Whether the photograph taken is a formally posed portrait or an instantaneous snapshot, the photographer looks at his or her subject with a direct and intense gaze that would generally be deemed impolite if no camera stood between them. The distance between them makes the photographic subject into the other—the thing that is to be photographed—but a necessary intimacy remains in the personal relationship between the photographer and his or her subject.

|

|

| |

“Yardstick” Photos

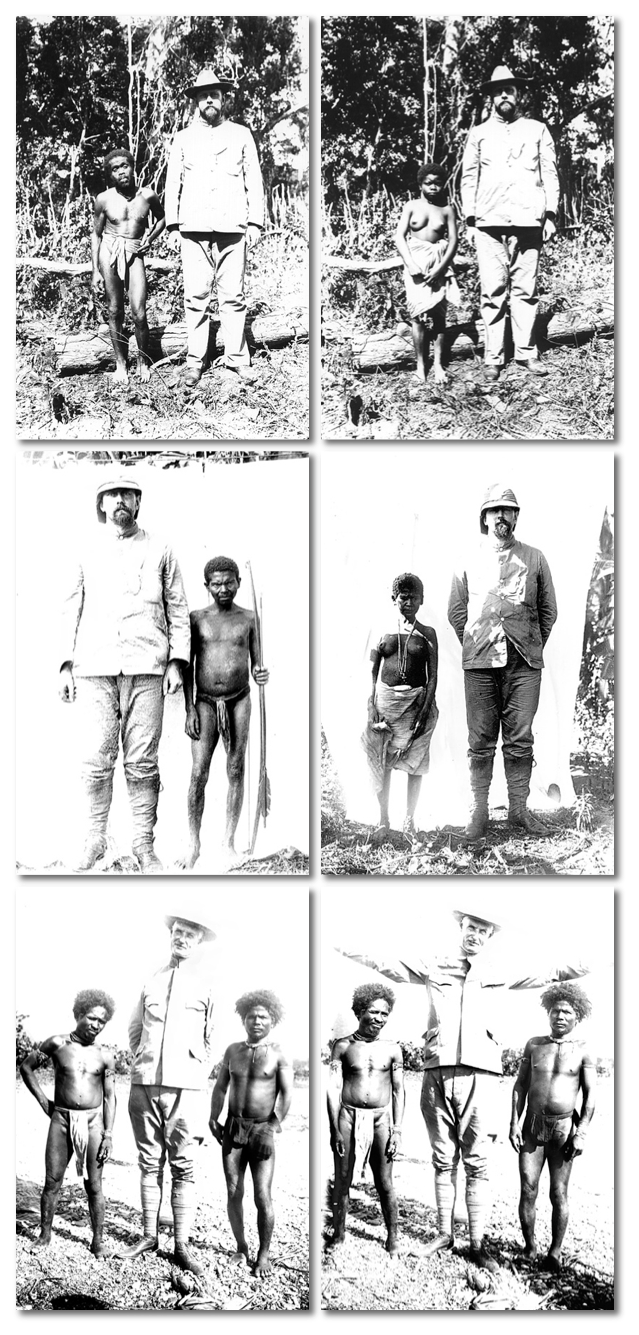

Dean Worcester does not appear to have engaged in the formal anthropometric measurement that many professional ethnographers used. Instead, Worcester and his fellow photographers used juxtaposition in their photographs in order to convey size, and sometimes even used their own bodies as yardsticks. Such depictions of scale can be found throughout the Worcester archive.

Photographs of Dean Worcester and, in the bottom two photos, Governor William F. Pack of Benguet Province, posed next to Filipinos as an ad-hoc yardstick measure meant, as his notes indicated, “to show relative size.” The images compared Pack and Worcester, relatively tall men, with Filipinos of the Negrito tribe—among the shorter people in the Philippines—making for a sharp contrast.

|

|

|

top left:

Worcester caption:

“Negrito man, type 1, and myself, to show

relative size,” 1901.

Location: Mariveles, Bataan

[dw001A002]

middle left:

Worcester caption:

“Negrito man, type 3, and myself, showing

relative size. Full length front view,” 1900.

Location: Dolores, Pampanga

[dw01H003]

bottom left:

Worcester caption:

“Two Negrito men with Governor Pack.

Full length front view, standing,” 1909.

Location: Palanan, Isabela, Cagayan

[dw01Z002]

|

top right:

Worcester caption:

“Negrito [wo]man, type 12, and myself

showing relative size,” 1901.

Location: Mariveles, Bataan

[dw01A041]

middle right:

Worcester caption:

“Negrito woman, type 5, and myself, showing

relative size. Full length front view,” 1900.

Location: Dolores, Pampanga

[dw01H010]

bottom right:

Worcester caption:

“Two Negrito men with Governor Pack.

Full length front view, standing,” 1909.

Location: Palanan, Isabela, Cagayan

[dw01Z003]

|

| |

Objects and Objectification

Turn-of-the-century anthropologists did not merely scrutinize, but also sought to document and to collect, another impulse that would have come as second nature to Dean Worcester. As a trained ornithologist, Worcester was familiar with the imperatives of collection, classification, and cataloguing. He had done that on his initial voyage to the Philippines as an undergraduate birdwatcher, and he continued it after his gaze turned from Filipino birds to Filipino people.

To see Filipinos as specimens for scientific study, Worcester had to turn human societies into laboratories.

|

|

| |

These images from Dean Worcester’s collection convey his impulse to catalogue and classify the Philippine culture around him, objectifying both people and cultural artifacts in the process.

[dw07_grid]

|

|

| |

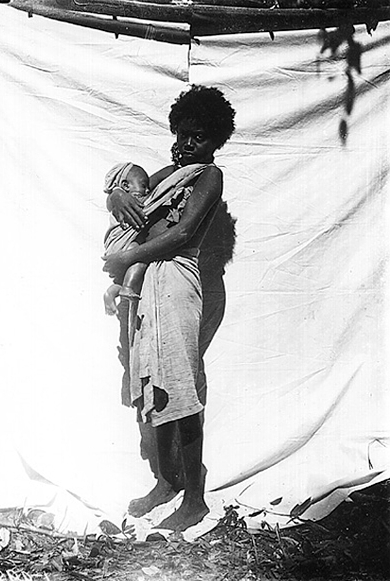

In one image taken in 1901, Worcester posed a young woman and her child before a white sheet draped to form a makeshift photo studio. Separated from her home, her community, and even from the culture that her portrait was meant to represent, the woman becomes an object of scientific scrutiny.

While Worcester and his team used a cloth backdrop in many photographs, many images feature subjects in natural environments. The varying degrees of posed and spontaneous scenes suggest additional complexities in the relationship between observer and observed.

|

|

Worcester frequently photographed his subjects in front of a hastily draped white sheet. This common photographic technique helped him take clearly-focused pictures, but also had the effect of separating his subjects from their cultures and communities.

Worcester’s caption: “Negrito mother with child in her arms. Full length side view,” 1901.

Location: Mariveles, Bataan

[dw01A098] |

|

|

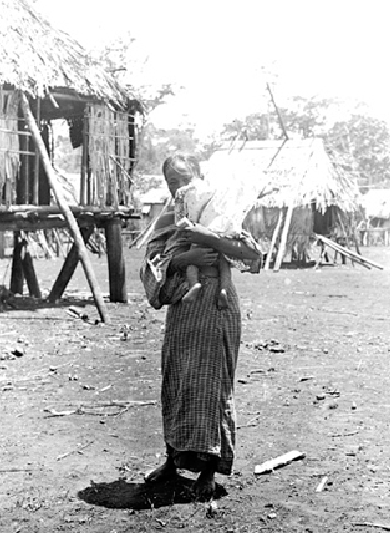

Here, by contrast, this mother and child were photographed without a backdrop.

Worcester’s caption: “Mangyan woman, type 8, with child. Full length front view, standing,” 1906. Location: Lalauigan, Mindoro

[dw03I012] detail |

| |

A white backdrop is apparent in this photo portraying Worcester’s colleagues and Filipinos—“observers” and “observed.”

Worcester’s caption: “Three Negrito women with

Winthrop, LeRoy and Dr. Kneedler,” 1901.

Location: Mariveles, Bataan

[dw01A113] detail

|

|

| |

Close observation of objects and objectification of individuals went hand in hand. Approximately 35 images in the collection depict ornaments, some photographed as details, as in this image of a hand with a “fresh tattoo.”

|

|

| |

Worcester’s caption: “Hand of Tinguiane woman showing fresh tattoo,” 1908.

Location: (Old Tauit) Burayutan, Apayao

[dw06HH002]

|

|

| |

The striking appearance of the young woman within the photographic frame belies Worcester’s effort to depict a disembodied image of bodily ornamentation. Many photographs in the Worcester collection document clothing, jewelry, and headgear, or document “exotic” cultural practices.

Worcester’s caption: “Left arm of Manobo girl, type 5. Showing ornaments,” 1908.

Location: Bakua, Butuan

[dw13B010]

|

|

| |

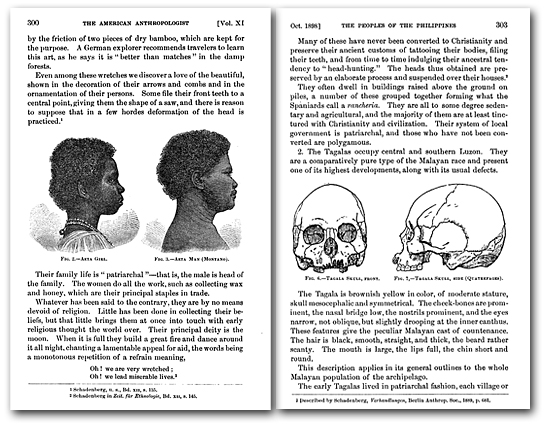

Photographs such as those in the Dean Worcester collection emerged from the practice of anthropometry, the scientific definition of races by use of measurements of the physical body. This effort drew on the latest techniques of criminology; indeed, the mugshot had only emerged in European photography in 1883. For Worcester, and for many of his readers back in the United States, such photographs were not only scientifically sound, but on the technological cutting edge. For Worcester, who would have been aware of the military and police uses of photography that were occurring in this era, the blend of anthropology and criminology that these photographs represent would have come as second nature.

|

|

|

| |

Scholarly studies of the Philippines by turn-of-the-century anthropologists included measurement of Filipinos’ bodies. Explicit (and usually unfavorable) comparison with European bodies confirmed white Americans’ sense of racial superiority.

Pages from Daniel G. Brinton, “The Peoples of the Philippines,”

American Anthropologist 11 (October 1898), p. 300, p. 303.

[1898_AmAnthopologist_p300_p303]

|

|

| |

Anthropology Meets the Mugshot

Observing Filipinos could also include measuring and documenting their bodies, as with the images of these members of the Kalinga tribe. Worcester frequently photographed his subjects seated in front and side views to document their clothing, jewelry, and hairstyles, but also to depict facial features that scholars would have used to classify them into races. Part of the developing science of anthropology, this photographic practice shared much with the criminal mugshots that were also common in this era.

|

|

| |

Top pair to bottom pair:

Worcester’s caption: “Kalinga man named Lauagan. This man followed us for three days with a head axe, constantly sneaking behind us and undoubtedly seeking an opportunity to kill us,” January 1905.

Location: Bunuan

[dw05a007] [dw05a008]

Kalinga man named Saking, January 1905.

Location: Bunuan

[dw05a005] [dw05a006]

Kalinga woman, August 1901, Island/Region: Cagayan

Location: near Tuguegarao

[dw05e006] [dw05e007]

|

|

| |

Staging the Primitive

Taxonomic organization of races, anthropometric measurement, painstaking documentation of objects and cultural practices were all attempts by Dean Worcester to stage his mastery of modern racial science. But the anthropological gaze could also look at “primitive” peoples to evoke Western stories of colonial adventure and romance.

Worcester’s journeys brought him into close contact with rural Philippine tribes, and he used his cameras to document the objects that he and other Americans found exotic and intriguing. Examining these photographs of the “head-axe”—a weapon that was typically used for hunting or harvesting but was sometimes used in the ritualized warfare that Americans called “headhunting”—reveals some of the attraction that violence and danger had for Worcester as he undertook his photographic work.

|

|

The Story of

an Axe

Americans were fascinated by the tool that they called the “head-axe.” Generally used for hunting or reaping crops, the axe’s sharp blade could also serve other purposes, including ritualized warfare that anthropologists described as “headhunting.” In this striking image of a young Kalinga man holding a head-axe, Worcester conveys a sense of danger and violence.

Worcester’s caption: “Young Kalinga warrior, type 3.

Holding head axe. Belonged

to party which attempted to

ambush us,” 1905.

Location: Bontoc, Cagayan

[dw05b004] detail |

|

| |

Stories of colonial adventure highlighted Americans’ ability to interact with the “primitive” peoples they met. Here, Worcester (seated on the left) and his traveling party appear with a group of Kalingas in the northern Philippine village of Pinakpook, but their head-axe is shown posing no threat to the American explorer.

Worcester’s caption: “Our party at house of Doget,” 1905.

Location: Pinakpook, Cagayan

[dw05d027] detail

|

|

Here, a Kalinga elder named Doget, Worcester’s host in the village of Pinakpook, poses for the camera in battle dress. In reality, most Filipinos would have used this axe as a tool, not a weapon.

Worcester’s caption: “Kalinga man named Doget,”

January 1905

Island/Region: Cagayan. Location: Pinakpook

[dw05d001] |

|

| |

Whether shown in the hands of a Filipino warrior or isolated against a backdrop, images of the head-axe conveyed the romance and danger of America’s colonial undertaking.

Worcester’s caption: “Three types of head axes in common use

among the Tinguianes of the Abulug River,” 1906.

Location: Bolo, Cagayan

[dw06ee013] detail

|

|

| |

Eroticizing Native Women

In contrast to his photographs of axe-wielding male warriors, Worcester’s images of women often feature an exoticism and danger of a different sort. For many American men, travel in the Philippines prompted fantasies of escape from the dictates of Victorian society. Worcester made several series of paired photographs of women that juxtaposed them with and without blouses.

|

|

Top left:

Worcester’s caption:

“Three girls from Kapangan, types

5, 6, and 7. Full length front views,” 1907.

Location: Trinidad, Benguet

[dw10L012]

Above left:

Worcester’s caption:

“Kalinga woman,” 1901.

Location: near Ilagan, Isabela

[dw05F030]

|

Top right:

Worcester’s caption:

“Three girls from Kapangan,” 1907.

Location: Trinidad, Benguet

[dw10L011]

Above right:

Worcester’s caption:

“Kalinga woman, type 11.

Full length front view,” 1901.

Location: near Ilagan, Isabela

[dw05f031]

|

| |

In this series of images of women by a stream, Worcester seeks to convey an erotically primitive state reminiscent of the innocence of the “Garden of Eden.” But the images of these Gauguin-like nudes are highly artificial stagings on Worcester’s part; note the woman’s clothing at her feet in the upper left photograph.

|

|

Upper Left:

Worcester's caption: “Benguet Igorot girl,

type 19. Full length front view, reclining

near stream,” 1904.

Location: Baguio, Benguet

[dw10A071]

Lower Left:

Worcester's caption: “Benguet Igorot

women, types 18 and 19. Squatting on

bank of stream,” 1904.

Location: Baguio, Benguet

[dw10A082]

|

Upper Right:

Worcester's caption: “Igorot woman,

type 23. Reclining near stream,” 1904.

Location: Baguio, Benguet

[dw10A181]

Lower Right:

Worcester's caption: “Benguet Igorot

women, types 18 and 19 in bath,

nude,” 1904.

Location: Baguio, Benguet

[dw10A087]

|

| |

We know little about how these images came to be staged or who was meant to see them, but it is clear here that Worcester’s gaze had jumped from the documentary impulse of the scientific photographer to the narrative imagination of the storyteller, even as the unequal power relations of colonialism made these images possible.

|

|

|