|

|

The City by Night These street-level views capture details of Tokyo on the cusp of change. Light from both natural and manmade sources suffuses the prints in a way that is distinctive to Kiyochika. The format of these Visual Narratives helps convey the delicacy, detail, and depth of these everyday scenes. Viewers can scroll down through the entire section, or use the menu below. The Visual Narratives are as follows: |

||||

| 1 – Gaslit City 2 – Spectacle & Spectatorship 3 – Moonlight & Shadows 4 – Night as Veil 5 – Modern Dissonance |

|

1 – GASLIT CITY Edo had maintained a “nightlife” as a traditional city culture, but it was mainly confined to the pleasure quarters. In his studies of Tokyo, Kiyochika demonstrates how new forms of illumination began to substantially transform the way life was lived. Although electric power would not be widely available until 1886, gas-fueled street lamps made a limited appearance in Tokyo around 1874, when around 80 were placed in the neighborhood of the Diet, or parliament building. The kerosene lamp was also becoming a fixture of modernity. The ability to engage in labor and leisure activities during what were once largely inaccessible hours changed the city’s appearance. Kiyochika used the opportunity to describe the newly illuminated night, indulging his continuing interest in lighting effects. |

|

Mount Fuji from Edobashi at Dusk, 1879 With Tokyo’s first gasworks, which began operating in 1874, the streetlamp joined telegraph wires and the ubiquitous rickshaw as a marker of new technology on the urban landscape. In this work, the gas lamp is a prominent framing device, though partially obstructed by a pine tree. Oil torches line the embankment, their flickering flames contrasted with the enclosed and steady stream of gas. The vantage point is from Edobashi, a bridge crossing Nihonbashi River, which recently had been re-built in stone. Nihonbashi, visible in the far distance, was built in wood, albeit in the Western style. Shown in vague silhouette behind it are Mount Fuji and a towering cumulonimbus cloud. Map location: #27 [s2003_8_1137] |

|

Night at Nihonbashi, 1881 Nihonbashi was Tokyo’s commercial center. It was also the first of the fifty-three stations of the Tōkaidō, a major artery connecting Edo and Kyoto. Traditional representations of the site included symbols of power, prosperity, and divine protection—the castle, central fish market, and Mount Fuji, respectively. However, these motifs are absent from Kiyochika’s composition. Instead, the artist focuses on capturing the ambiance of a gas-lit metropolis. Wrapped in the purplish haze of new artificial light, people strolling through the city take on a ghost-like appearance. Landmark buildings are indistinguishable in the shadows, heightening the sense of disorientation. A year after this print was created, the horse-drawn carriage seen proceeding down the sectioned off center would be superseded by trolley cars. Map location: #28 [s2003_8_1187] |

|

Summer Night at Asakusa Kuramae, 1881 The setting of this print is north of Asakusa Bridge, the former location of shogunal rice granaries at which Kiyochika’s maternal family had been employed. The artists returned to this place of childhood at dusk, during the magic hour when streetlamps are lit one by one. Tonal gradations from sooty grey to blue to purple express the gradually darkening sky with traces of lingering daylight. Silhouetted figures of pedestrians are black and defined in the foreground, soft grey and barely visible in the distance, thus evoking the breadth of the newly widened boulevard. The regular spacing of streetlamps on the far side of the thoroughfare is discerned only by star-shaped emissions of light. Map location: #29 [s2003_8_1190] |

|

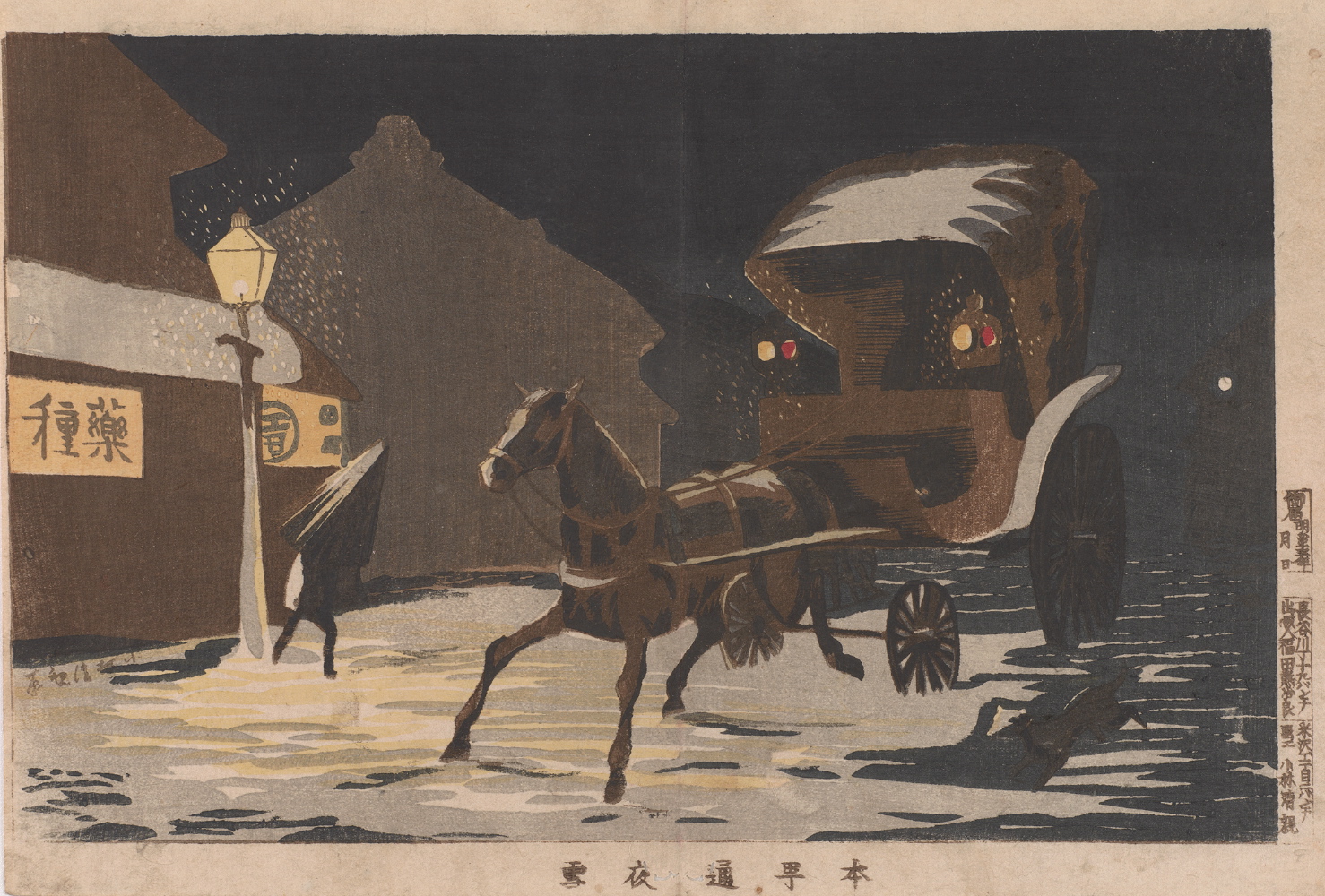

Night Snow at Honchō-dōri, 1880 A horse-drawn carriage thunders by Honchō-dōri, in Nihonbashi’s wholesale pharmaceuticals district. A dog racing alongside underscores a sense of urgency and speed. The gas lamp illuminates a store sign that reads “drugs”. The street appears deserted, save for a lone pedestrian trudging forward against heavy snow. Kiyochika’s visual acuity is demonstrated in the way he attempts to show the effects of gaslight in snow. Here a street lamp casts a pool of diffused light on the white blanket of snow, giving the scene a stage-like, spotlighted aspect. Silently falling snow is visualized only when in proximity to light sources, such as the lamp stand or suspended lanterns flanking the moving vehicle. [s2003_8_1122] |

2 – SPECTACLE & SPECTATORSHIP Few things are more distinctive and striking in Kiyochika’s views of emerging Tokyo than his depictions of people. Particularly in nocturnal settings, Kiyochika renders the human form in silhouette, or as somehow remote, singular, and absorbed. His compositions often suggest a stage; the viewer looks at the depicted audience, which in turn observes an event, frequently a new phenomenon within the city or some new form of light. The pleasure traditional Japanese artists took in depicting the variety and vitality of human activity has nearly vanished from Kiyochika’s scenes. Kiyochika left no written record of his intentions, but the severe disconnect between his cityscapes and those of his predecessors suggests that he was trying to depict a new kind of human walking the roads and bridges of Tokyo—one who is disengaged, alert, observing, and waiting. |

|

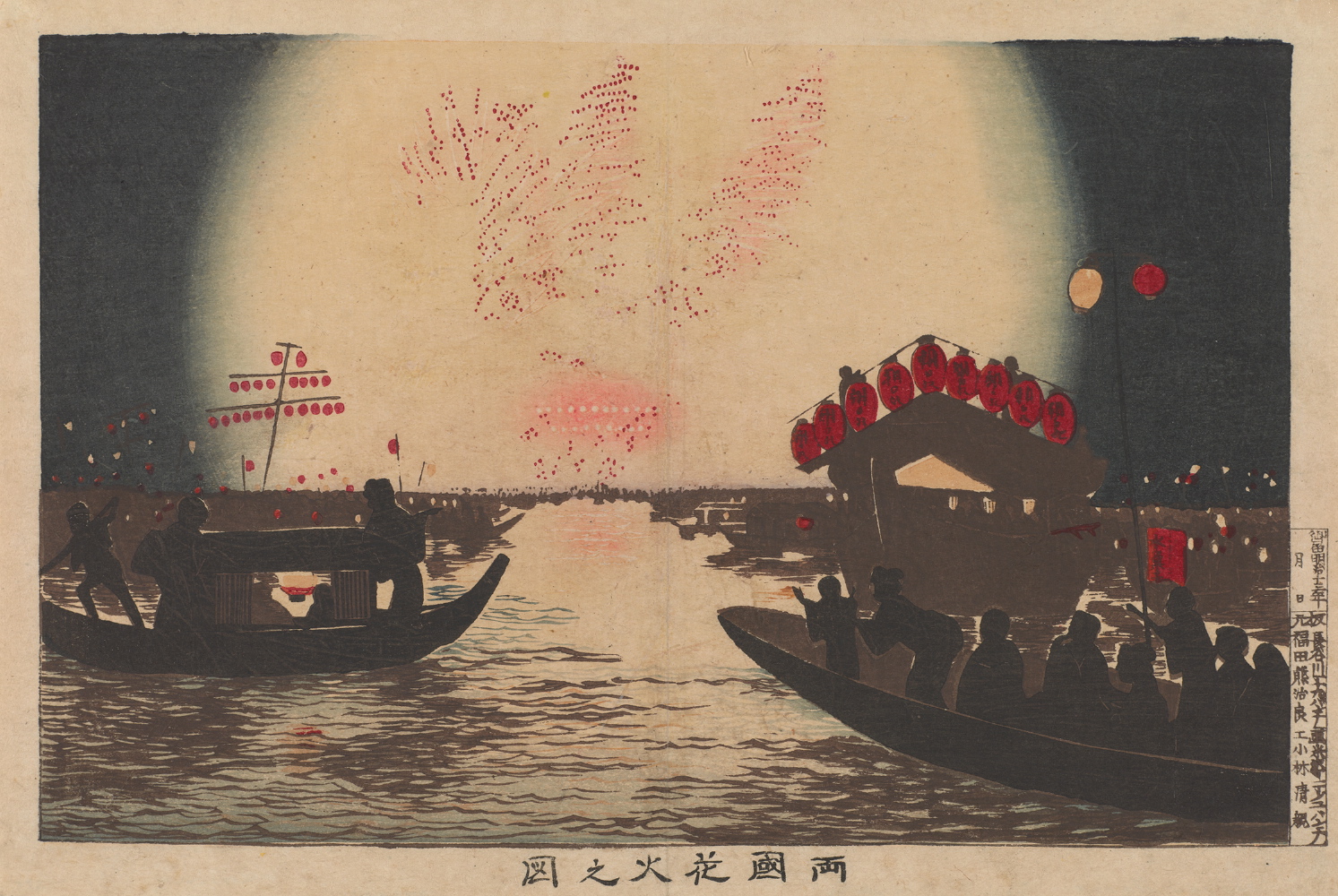

Fireworks from Ikenohata, 1881 The buoyant atmosphere of spectacles at night is captured in this scene depicting fireworks at the Ryōgoku Bridge. A variety of pleasure boats is shown, from open-roof to covered ones for private hire. A fruit vendor peddles “water sweets“ at this popular summer attraction. The vantage point is at water level. Kiyochika enhances the realism of this perspective by focusing on the theatrical animation of spectators in the foreground. The figures are shown in silhouette, marveling at the spherical halo of light. The rippled surface of the water, illuminated by the fiery explosion, appears as an almost photographic rendering. Location on map: #33 [s2003_8_1197] |

|

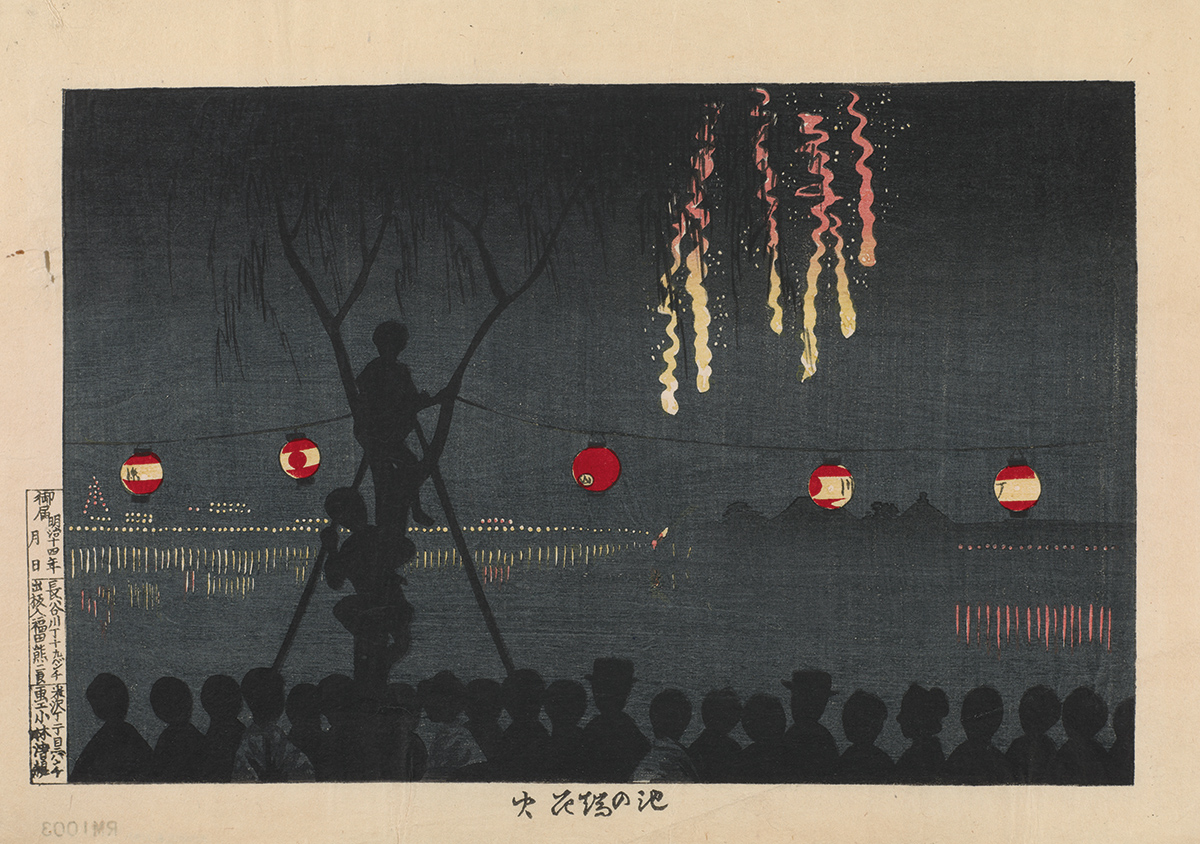

Fireworks at Ryōgoku, ca. 1880 Spectators climb a willow tree to get a better view of fireworks from the edge of Shinobazu Pond in Ueno. Kiyochika makes a visual pun, juxtaposing the tree’s branches with cascading ribbons of light known in fireworks parlance as “the weeping willow.” While Edo-period fireworks had been monochrome, the slow-falling trail of sparks shown here is tinted with color, pyrotechnically made possible in the Meiji era with the use of imported chemicals. Silhouetted spectators lining the bank and in the tree frame the object of attention. [s2003_8_1194] |

|

Night Stalls at Asakusa, 1881 The myriad shops that lined the approach to the Asakusa Temple constituted one of Edo’s oldest and most popular shopping arcades. Previously depicted by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) and other traditional designers from a bird’s-eye perspective, Kiyochika’s view of the nighttime throng is that of a slightly detached participant. New forms of lighting technology, including the supernatural glow of carbide lamps, emerge from the center of the market’s activity and command the scene by defining the night and its spectators. Individuals, whether depicted in silhouette or seemingly mesmerized by light, have lost the animated postures of engagement typically seen in market transactions; instead, they stand transfixed. Location on map: #34 [s2003_8_1191] |

|

Year-end Market at Sensōji, 1881 The toshi no ichi was a traditional market held toward the end of the year, when the people of Edo would make their annual excursion to purchase decorations and specialty food items for New Year festivities. The turning of old to new is underscored by the juxtaposition of new Meiji-era symbols, such as the telegraph pole, streetlamp, and Western-style building, with more traditional elements, such as street performers, paper lanterns, and temple structures, shown in silhouette. In Kiyochika’s composition, there is none of the rowdy, rambunctious atmosphere that surrounded the festivals and spectacles of Edo. In spite of the obvious range of activity depicted, the foreground row of silhouetted figures defines the intended perspective; Kiyochika invites the viewer to observe the observers. Location on map: #35 [s2003_8_1107] |

3 – MOONLIGHT & SHADOWS The writer Nagai Kafū (1879-1959) was one of a number of 20th-century Japanese intellectuals who championed Kiyochika’s work. He used his collection of Kiyochika’s prints both as inspiration for his novels and as a nostalgic guide for his strolls through Tokyo, seeking relics of a transitional city already escaping his grasp. Lamenting the demise of old Edo’s appearance and ambiance, Kafū read in Kiyochika’s views a similar longing for the past, as well as a sense of unease about the future. |

|

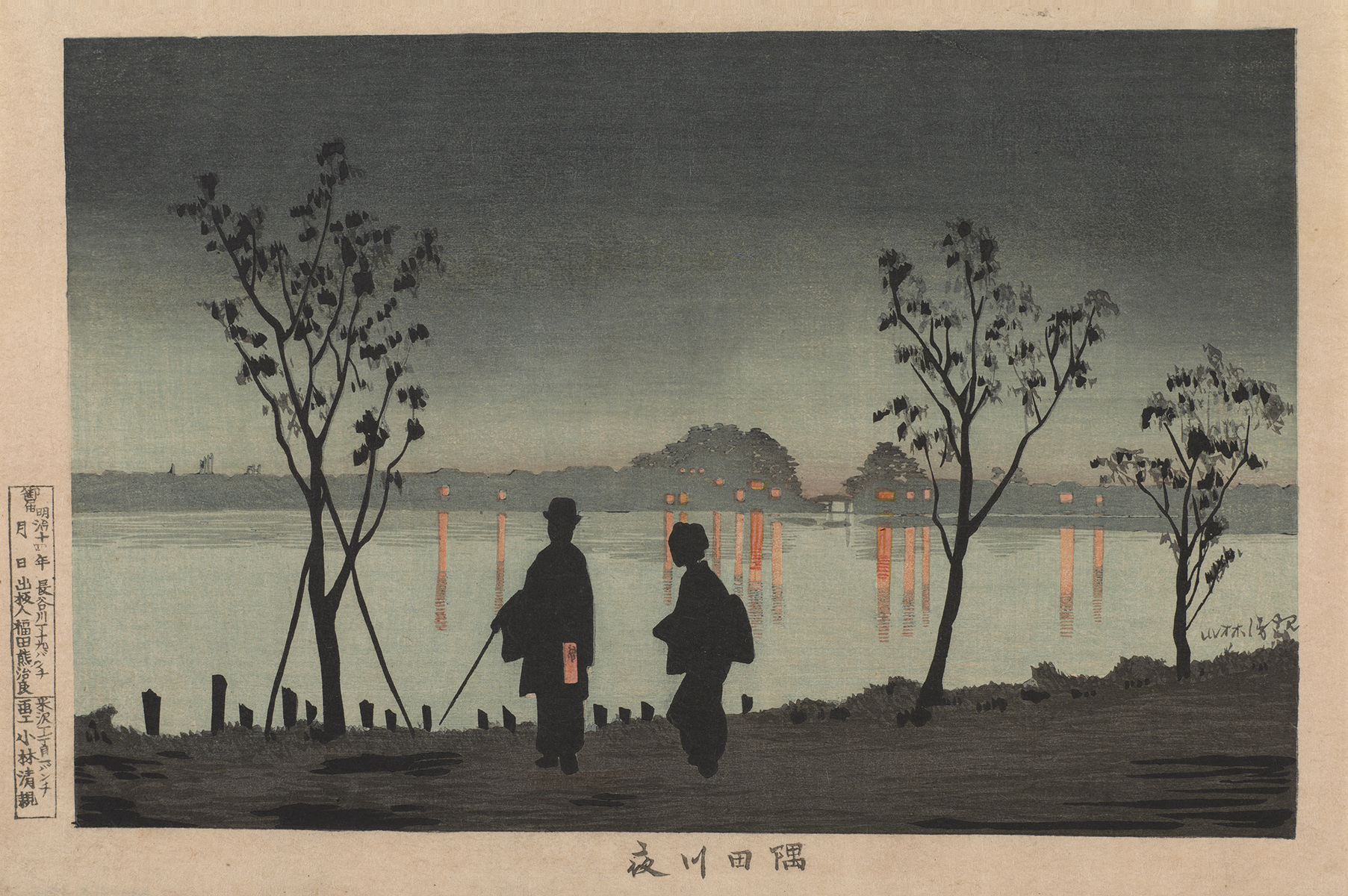

Sumidagawa at Night, 1881 One of Kiyochika’s iconic works, this print is often associated with Nagai Kafū’s 1909 novel Sumidagawa (The Sumida River), in which the protagonists serve as pretexts to write about Tokyo’s vanishing famous sites. In the print, the two characters silhouetted against the night sky are a geisha, with a traditional hairstyle, and her patron, wearing a Western-style hat. The couple stands on the eastern bank of the Sumida River at Mukōjima and looks to the western bank at Asakusa and Imado. The humpbacked bridges in the distance and the reflection of distant lights in the river contrast with the nocturnal sky and its subtle shades of grey and black. [s2003_8_1202] Map location: #1 |

|

Rainy Night at Yanagiwara, 1881 The neighborhood of Yanagiwara takes its name from willow trees lining a stretch of the south bank of Kanda River. Barely visible in the far distance at left is a faux-Western/Japanese hybrid building identified as the Tax Bureau Office. Obstructing the view is a covered rickshaw and a cabby captured mid-gesture as he calls to clients. Only a stray dog takes notice. |

|

Kiyochika created a number of impressions for this design, evidencing his experimentation with tonalities. Night is not simply rendered in the classic raven-wing black but expressed as a subtle array of grey, dark blue, and greenish hues. In one impression, he added diagonal streaks of silver mica, presenting a more overt representation of night rain. Map location: #31 [s2003_8_1181-1185] |

|

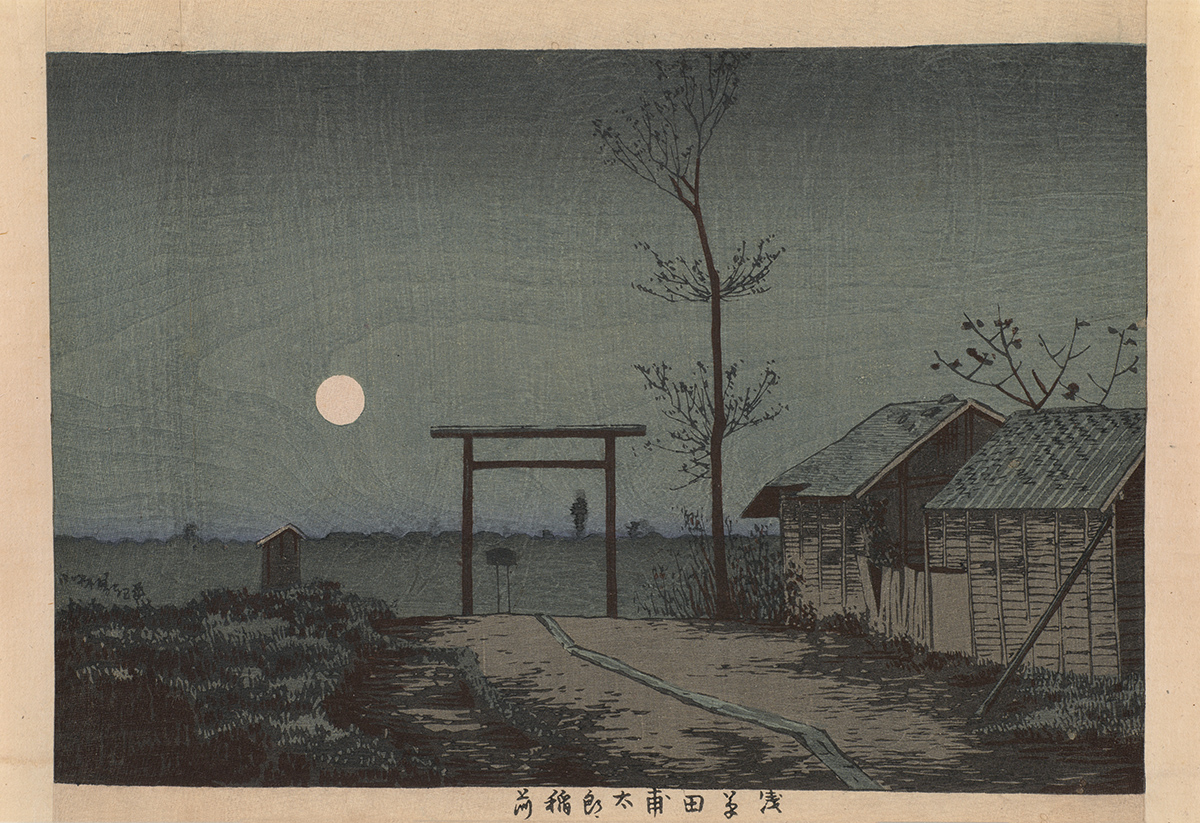

Before Tarō Inari Shrine at the Asakusa Ricefields, 1881 In Japan, the spirit of Tarō Inari is revered in a vast number of Shinto shrines. Distinguished by vermillion-painted gateways (torii), these sites also have images of foxes (kitsune), usually in male-female pairs. The fox was thought to be an incarnation of the Inari spirit or a messenger to that deity. In addition, the fox, a wily shape-shifter, often was associated with seduction. Thus, Inari shrines were often in close proximity to pleasure quarters. This print suggests nothing of the gaiety, noise, and color that surrounded an Inari shrine filled with petitioners. Kiyochika’s view is of a deserted shrine near an area of ramshackle brothels known as Asakusa Yoshiwara. The path meanders beyond the gateway to an indeterminate future. One of the last of Kiyochika’s ninety-three images of Tokyo, its sense of haunting desolation permeates the view. Map location: #23 [s2003_8_1174] |

4 – NIGHT AS VEIL At night, the modernizing enthusiasms of the Meiji government became cloaked in shadows. With the city embraced in darkness, topographical boundaries between old and new, center and periphery, urban and rural, became soothingly blurred. A romanticized, countrifying, lyricizing view could be mediated by the presence of fireflies or, more often, by moonlight. |

|

Teahouses by Imadobashi, ca. 1877 The Imado Bridge, built over the Sanya Canal, was in its heyday one of the major points of access to the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters. Under the bridge and all around it were landing places for the slender roofless boats that carried Yoshiwara’s visitors. Kiyochika’s print focuses on two teahouses connected by this bridge, though, in the moonlit night, no sign of traffic is observed on the canal. In Kiyochika’s day, Imado was becoming rundown and distant in style and clientele from those of Edo times. This work emphasizes the contrast between the lit interiors of the teahouses and lanterns carried by attendants—the flicker of the past and the anonymity of the new “classless” society. Map location: #3 [s2003_8_1114] |

|

Distant View of Ichinohashi from the Banks of Sumida River, 1880 When accommodating early Western diplomatic and commercial missions, the Japanese strove for a polite isolation of these still unknown and thoroughly exotic visitors. Ishikawa and Tsukiji, two islands reserved for habitation by foreigners, were in the bay just to the east of Shinbashi, the new Tokyo’s central transportation hub. Ichinohashi Bridge connected the islands. On outings and excursions to the foreign concessions, the Japanese could gawk at the novelty of transplanted Western customs, all the while unwittingly becoming modern. Kiyochika combines some of his favorite themes in this print: a nocturnal landscape, various sources of light, and silhouettes of characters and buildings. In this nightscape, he subtly associates the pleasures of the old Edo (the geisha) and modern innovations (the rickshaw). He also provides one of the last views of a site that would soon be completely transformed. Map location: #4 [s2003_8_1119] |

|

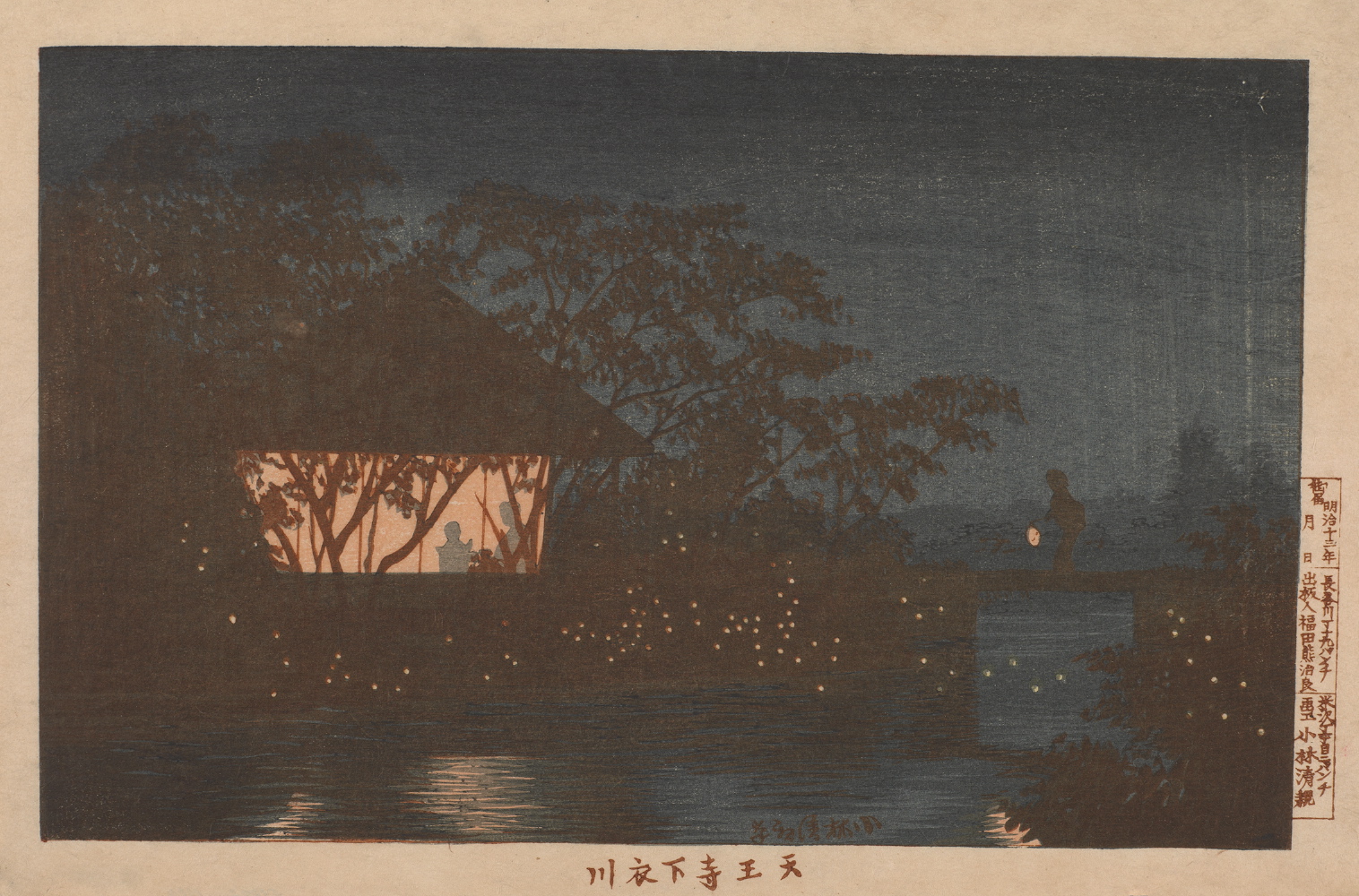

Koromogawa River at Tennōjishita, 1880 The title of this print alludes to a tributary nestled in the swampy area of Yanaka, in Ueno, and near a new museum designed by Josiah Conder. The proximity to the encroaching modern landscape is not evident in this scene, yet the contemporary Japanese viewer would have understood Kiyochika’s suggestion that two distinct worlds coexist under the cover of darkness. [s2003_8_1178] |

|

Fireflies at Ochanomizu, 1880 A roofed pleasure boat slowly floats down the water at twilight. Despite the summer pastime’s bucolic association, the setting is Kanda River, in the heart of the city. In this composition, Kiyochika employs a vanishing-point perspective and subtle tonal gradations to express the depth of the quickly descending darkness. The delicate glow of fireflies—rendered in two shades of yellow—serves to emphasize the night’s seductive pull. It is interesting to note that the American artist James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), who was fascinated with the “veiling” effect of the evening on the Thames, also used numerous pinpoints of light to structure darkness in his paintings. Map location: #36 [s2003_8_1131] |

5 – MODERN DISSONANCE The infusion of Western technology into Japan from the beginning of the Meiji era (1868–1912) spurred widespread visual documentation of the new developments. Railroad transportation, telegraphic communication, gas—and later, electric—lighting, steam-powered river and ocean vessels, and new materials and designs for bridges and buildings were crammed into the Japanese landscape over two decades. While not always technically precise, Kiyochika’s renderings captured the essence of these modern innovations. In an interpretive context of light, shadow, delicately controlled chromatics, and subtle juxtaposition, he gave a highly nuanced commentary on the emerging values of the new world. |

|

Shinbashi Station, 1881 Japan’s first railway line was inaugurated in 1872 amidst much fanfare. While the Renaissance-style station in Tokyo was celebrated in countless kaika-e (enlightenment pictures), here it appears to sink back into shadows. Kiyochika seems more interested in describing how light flooding from the structure’s interior is refracted on the rain-soaked ground and the glistening, shimmering aspect of the wet surface. At the foreground of this picture is the complex play of station lights, lantern lights, and light diffused through oil-coated paper umbrellas. The resulting polyphony of luminosities is one of the most masterful in his entire series. Map location: #30 [s2003_8_1199] |

|

View of Takanawa Ushimachi under the Shrouded Moon, 1879 Kiyochika made this print in 1879, seven years after a rail line opened to connect Shinbashi in central Tokyo with Takanawa, about four miles down the coast of the bay. However, it seems that Kiyochika was depicting a type of locomotive that had yet to make its appearance in Japan. In anticipation, he borrowed liberally from a Currier & Ives lithograph of the engine. This study of light—perhaps Kiyochika’s most highly regarded—posits the train as the vehicle of modernity; it belches controlled fire and casts transforming rays from its headlamp, cabin, and carriage. The illumination provided by the dramatic, shifting, and grandly unpredictable sky contrasts with the modern light. Passengers in this journey are ghostly silhouettes, a form used again and again by Kiyochika to depict humans in this newly available night. Map location: #5 [s2003_8_1179] |

|

Moonlit Sea at Kawasaki, 1879 Kiyochika again creates an imaginary scene in this print, likely inspired by another Currier & Ives lithograph. The point of view here is ambiguous, but it presumably suggests that Japanese people are observing foreign battleships in a firing exercise, held in Tokyo Bay off of Kawasaki to the south of Tokyo. The print is an essay on light—Kiyochika’s mix of natural moonlight and the violent bursts emitted from these dark and relatively unfamiliar hulks. This image is prescient. Later in his career, Kiyochika would produce woodblock-print accounts of two of Japan’s expansionist wars with China (1894–95) and Russia (1904–5). In each instance, Kiyochika relied on reports from the front to imagine dramatic scenes of land battles, and engagements on the high seas. [s2003_8_1143] |

|

Rainy Moon at Gohon-matsu, 1880 The Japanese language first accommodated the concept of “steamboat” in 1853. Here, Kiyochika establishes contrasts between the figures who stroll along the bank carrying traditional lanterns and umbrellas and the sleek steamboat slicing through the canal. Light reflected on the rain-dampened path and on the river are two irresistible points of observation for the artist. Gohonmatsu (five pines), an auspicious bend on the Onigawara Canal in Edo, was named for five auspicious pines. The trees grew on the estate of Baron Kuki Ryūichi (1852–1931), keeper of the imperial art collections and a prominent art collector who had significant interactions with Westerners. By Kiyochika’s time, only one tree remained, but it still encapsulated the pine’s essential meaning of longevity. Map location: #6 [s2003_8_1192] |

|

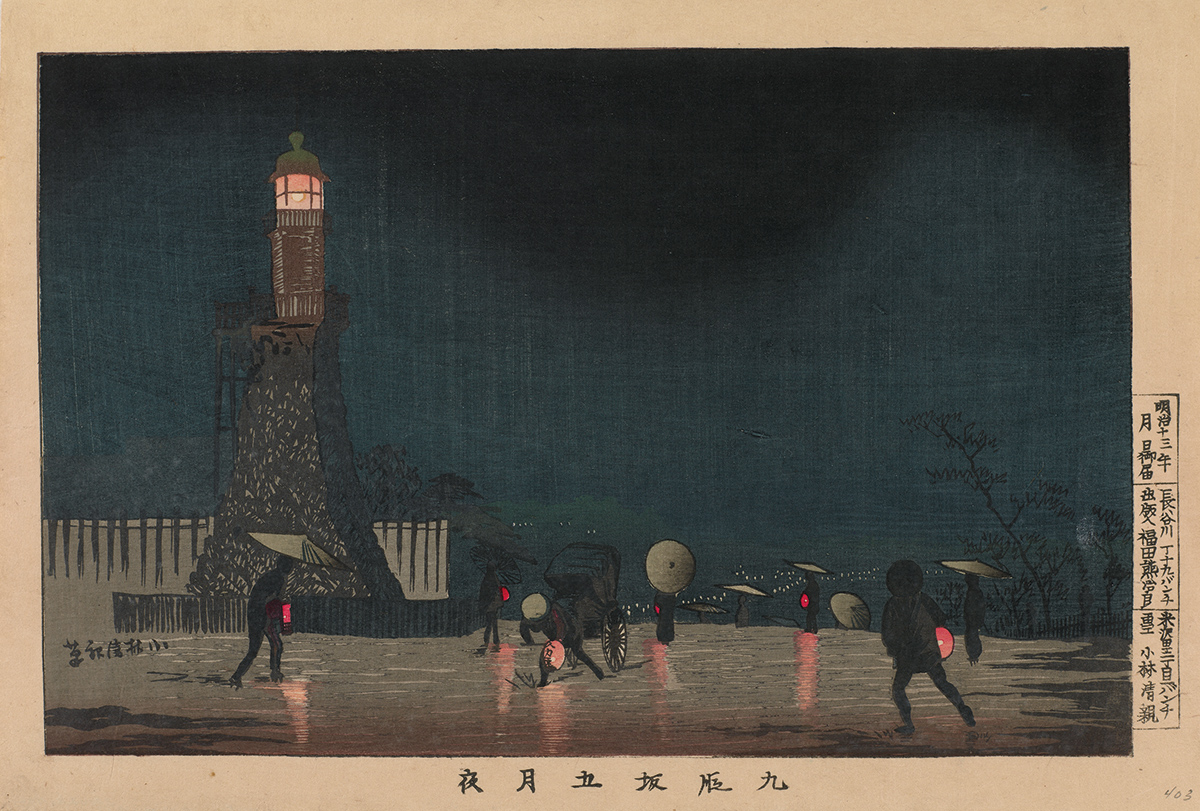

Kudanzaka at Night in Early Summer, 1880 With the establishment of Yasukuni Shrine in Kudanzaka in 1869, the site became a landmark as a memorial to Japanese fallen soldiers. The adjoining Western-style lighthouse, constructed purportedly to appease the souls of those who had died bringing about the Meiji Restoration, also guided ships in Shinagawa Bay. In his novella Black Hair, Meiji-era writer Izumi Kyōka (1873-1939) notably feminized the structure, likening the stone base to the fall of a woman’s kimono. Kiyochika achieved this print’s rich nuances of dark sky with the bokashi technique. He rendered hues ranging from light to dark by applying pigment in a gradient to a moistened woodblock. The standard process of inking the whole block with a single pigment value was much more efficient, but the effect was less subtle. Map location: #32 [s2003_8_1106] |

|

Umaya Bridge, ca. 1880 In 1874, the Umaya Bridge was built over the Sumida River, connecting the areas of Kuramae and Komagata on the western bank and Honjo on the eastern bank. This bridge was one of the first modern infrastructures constructed in the reign of the Meiji emperor. Umaya means “horse stables” and refers to the shogun’s stables, which were once located near the bridge’s western end. The scene described here is a torrential storm. Pedestrians scurry under lashing rain. Kiyochika contrasts poles that uphold telegraph wires with the ominous force of the storm. Map location: #7 [s2003_8_1110] |

These prints by Kobayashi Kiyochika are from The Robert O. Muller Collection of the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution |

Massachusetts Institute of Technology © 2016 Visualizing Cultures Creative Commons License |

|

|