| |

ETHNOLOGY & EXPLORATION

Ethnology in Formosa

Volume 1 of Illustrations of China and Its People concerns itself almost entirely with Hong Kong and Canton, which by the late 1860s had superceded Shanghai as the premier outposts of British authority in China. Canton had long been the trading port favored by British merchants, and Hong Kong was formally recognized as British territory in the 1842 Treaty of Nankin that followed the first Opium War. Thomson’s treatment of these sites thus focuses primarily on the British presence.

Volume 1 closes with an image of a Formosa mountain pass, however, and Volume 2 opens with a similarly rural scene of a bamboo grove on Formosa. These photographs stand in marked contrast to the scenes of Western-style architecture in Hong Kong, and are intended to emphasize the transition from the civilized world of the colony to the remote and primitive environment of Formosa. This transition sets the scene for an ethnological adventure among Formosa’s semi-civilized native tribes.

|

|

|

“A Mountain Pass in the Island of Formosa” “A Mountain Pass in the Island of Formosa”

plate XXIV, volume 1

ct1106 (caption) ct1107 (photo) |

“Bamboos at Baska, Formosa” “Bamboos at Baska, Formosa”

plate I, no. 1, volume 2

ct2010 (caption) ct2011 (photo |

|

| |

Thomson lays the groundwork for the ethnological study he will pursue on Formosa in the caption for “Mountain Pass” by dividing up the island according to the ethnicities and cultural practices of its inhabitants:

The central range of mountains, together with the lower ranges to the west, the spurs thrown off to the east, and a great portion of the eastern coast, are still inhabited by aboriginal and independent tribes. These, in configuration, color, and language, resemble Malays of a superior type. Akin to them are the Pe-po-hoans, who dwell on the low hill lands and plateaux to the west of the central mountain chain. These Pe-po-hoan tribes are partially civilized, supporting themselves by agriculture, and being to some extent subject to the Chinese yoke. Outside of these districts, and occupying the fertile plains to the west, Chinese planters from Fukien province are to be found: and intermingled with them are the Hak-kas, a hardy, industrious, and adventurous race who emigrated from the north of the empire. The Hak-ka Chinese hold the lands nearest to the savage hunting-grounds. They also make alliances with the mountain tribes, and carry on trade of barter, exchanging Chinese wares for camphor-wood, horns, hides, rattan, etc.

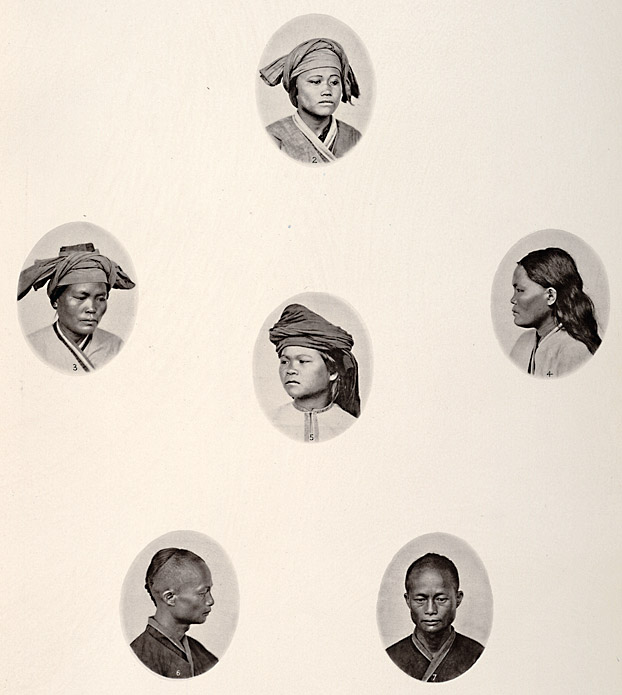

This brief sketch of Formosa’s demographic geography provides the background for what is perhaps the most important image/caption pairing in Thomson’s ethnological project, a plate of six cameo photographs titled “The Natives of Formosa.” As the first of several similar plates, this image introduces the protocol by which Thomson’s understanding of ethnology takes visual form. The caption also situates Thomson’s concerns solidly in the middle of the debates concerning race, ethnicity, and culture that preoccupied the British scientific community in the mid-to-late-19th century. 4

|

|

|

| |

“The Natives of Formosa,” plate II, nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, volume 2

ct2012-ct2013 (caption) ct2014 (photo)

|

|

| |

The lengthy caption for this image begins with a reiteration of the geography and demographics presented with the “Mountain Pass” image noted above. This serves to narrow Thomson’s study of Formosa’s four primary ethnicities down to the Pepohoan. 5 The subjects in these photographs are all from Baksa, the only native village Thomson visited in Formosa. Thomson characterizes the Baksa Pepohoan as “the most advanced types of those semi-civilized aborigines, who conform so far to Chinese customs as to have adopted the Amoy dialect, the language in use among the colonists from China.” Referring to the two male heads in the lower register of the plate, Thomson states: “The men of Baksa wear the badge of Tartar conquest, the shaven head and the plaited queue, attributes of modern Chinese all over the world.” Tartar refers to the Manchu, a northern, non-Han Chinese people who ruled China from the mid 1600s to the early 1900s. Thomson’s description of Baksa women shown in the four upper cameos stands in sharp contrast to that of the men: “The women, however, have a more independent spirit, and adhere to their ancestral attire.”

Thomson’s approach here signals his awareness of one of the more urgent imperatives facing mid-19th-century ethnologists. The Ethnological Society of London (ESL) was founded in 1843 by a faction seeking to break free from the religious (i.e., Quaker) affiliations and anti-colonial politics of the Aborigines Protection Society (APS). The breakaway faction sought to frame their goals and practices in purely scientific terms. Not all APS concerns were jettisoned however. Since the late 1850s, the APS had been lobbying on behalf of aboriginal peoples whose cultures were disappearing with the onslaught of colonization. In this milieu, photography emerged as the preferred technology for preserving dying cultures.

This so-called “salvage ethnology” provided a powerful motivation to acquire portraits of aboriginal peoples. 6 In this endeavor, moreover, ethnologists focused on aboriginal females, believing that they were more reliable repositories of traditional culture. Thomson’s treatment of the Pepohoan thus deploys all the hallmarks of salvage ethnology. He offers a unique variation on this paradigm by casting Chinese in the role of colonists threatening extinction of a primitive people, but seems blind to the irony of this argument. His scenic views of the treaty ports, after all, present Western colonists as a civilizing influence on China.

Proceeding with his assessment of the Pepohoan, Thomson makes several comparisons in order to place his subjects in broader geographies and ethnological discourses. He notes that the ancestral attire worn by Pepohoan women “closely resembles in its style the dress of the Laos women whom I have seen in different parts of Cambodia and Siam.” Thomson then uses this comparison to define the parameters of his ethnological practice.

It will be readily perceived by those who have lived in China and in the Malayan Archipelago, that the features of the type here presented display a configuration more nearly akin to that of the Malay races who inhabit Borneo, the Straits settlements, and the islands of the Pacific, than to that of the Mongolian, and Tartar tribes of China. This affinity of race is indicated still further by the form and colour of the eyes, the costume, and the dialects of the people of Formosa.

Emphasizing visual and linguistic comparisons places Thomson’s methodology within several evolving debates in the British scientific community.

20 years after its founding, the ESL faced the departure of one of its own factions when, in 1863, several members broke off to form the Anthropological Society of London (ASL)—a complex subject in itself. ASL members were politically conservative; unlike the ESL, for example, they refused to extend membership to women. In general, they subscribed to a belief in polygenesis, the idea that each race developed from distinct and separate origins. They were vehemently opposed to the possibility that the Caucasian and negroid races shared a common ancestry. By contrast, the ESL membership was far more open to the possibility of monogenesis—the argument, that is, that all races descended from a single ancestor, with differences attributable to environmental factors. Darwin’s concept of evolution (introduced in 1859) helped proponents of these opposing views reconcile their differences, and in 1871 the ESL and ASL reintegrated to form the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (RAI).

Philosophical and institutional reconciliation, however, by no means diminished the inherently racist attitudes held by the members of these societies. Using Darwin’s theories, racial differences were plotted along an evolutionary continuum with Caucasians seen as more evolved and therefore superior to other races. Africans were thought to be incapable of civilization. Orientals once possessed superior civilizations that had now fallen into ruin. Native Americans and Southeast Asian aboriginals, such as the Pepohoan Thomson photographed, were identified as independent races which were placed below Caucasians on the evolutionary continuum. 7

The ESL and ASL also differed in their practices. Ethnologists focused primarily on differences in language and culture to document relationships among various peoples. Anthropologists focused on physical appearance—skin, hair, and eye color, for example—but also anatomy. Anthropometry, the measurement of skeletal and cranial structures, provided the primary technology for documenting racial differences along anatomical parameters.

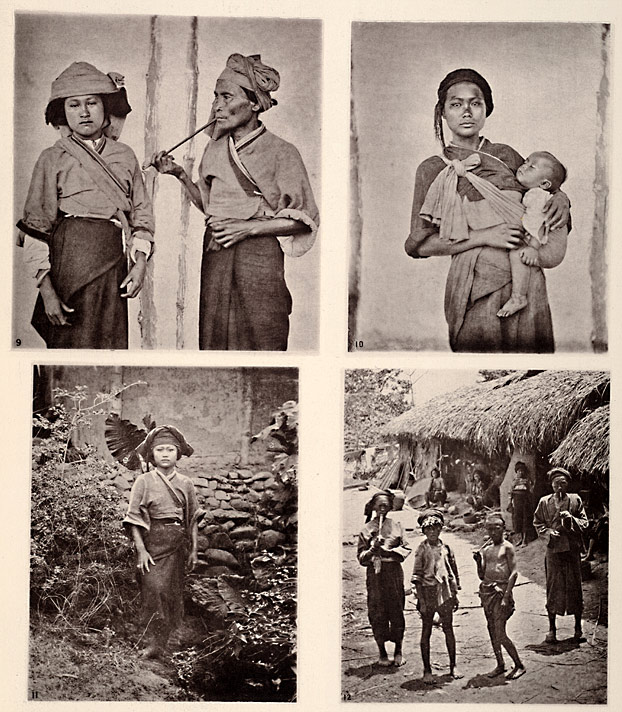

Because both the ESL and ASL methodologies focused in part on documenting visual differences among indigenous peoples, photography played an increasingly important role in their practices. The 1852 British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) Manual of Ethnological Enquiry advocated using photography to collect study images but provided little direction as to the sort of images that would be most productive. Early ethnological photography tended to be somewhat ad hoc as a result. In Illustrations of China and Its People, for example, Thomson’s types include the cameo portraits noted above, three-quarter-length portraits with neutral backgrounds intended to facilitate study of both head and costume, full-length portraits that situate their subject in their native environment, and village scenes featuring indigenous architecture and multiple subjects engaging in cultural practices of interest to ethnologists.

|

|

|

| |

Clockwise from upper left: “Pepohoan Women” no. 9

“Mode of carrying Child” no. 10

“Costume of Baksa Women” no. 11

“Lakoli” no. 12

“Types of the Pepohoan,” plate IV, volume 2 (detail)

ct2018-ct2019 (caption) ct2020 (photo)

|

|

| |

“A Pepohoan Dwelling,” plate III, volume 2 (detail)

ct2015-ct2016 (caption) ct2017 (photo)

|

|

| |

In 1869 Jones H. Lamprey, a member of both the ESL and the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), attempted to standardize the photography of indigenous peoples with what came to be known as the “Lamprey Grid.” It consisted of a large black panel with white strings stretched vertically and horizontally across its surface to form a grid of two-inch squares. Nude aboriginal subjects were to be photographed standing before the grid in frontal and profile views. The two-inch squares would thus provide the means to make anthropometric studies of the subjects. Thomas Henry Huxley, then President of the ESL, advocated a similar project in 1869. He argued for front and profile views of nude native subjects posed with measuring sticks. Both the subject and the measuring stick would appear in the same plane of the photograph, thus enabling anthropometric assessment. Apart from a few isolated case studies, Lamprey and Huxley’s methods ultimately proved impractical, primarily because they required subjects from cultures willing to submit to these intrusive practices. 8

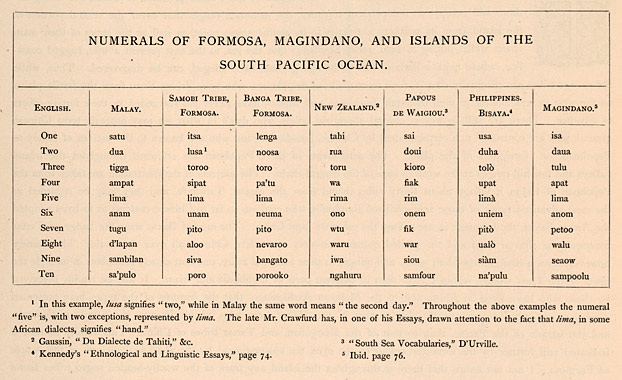

Where, then, do Thomson’s ethnographic photographs and their captions fit within the institutional histories and methodologies of the ESL and ASL? Clearly his preferences lay with the ESL—before departing for China in 1867, he joined this institution, not the ASL. But perhaps the best evidence of his affiliation can be found in the arguments supporting his conjecture that the Pepohoan were similar to Malays and Laotians. Thomson’s caption highlights visual similarities but in a decidedly ethnological as opposed to anthropological argument. He also supplied linguistic evidence in the form of a table comparing the numbering systems of Malays, Formosans, Magindanoans, and South Pacific Islanders.

|

|

|

| |

“In the table subjoined, I have contrasted the Formosa numerals with one or two examples taken from the languages spoken in the islands of the South Pacific, and I may add, that a more extended comparison of the vocabularies of Formosa and the Pacific Islands only tends to prove the common origin of the whole of the races who people them.” (from caption)

“The Natives of Formosa”

Chart: Numerals of Formosa, Magindano, and Islands of the South Pacific Ocean, caption page, volume 2 (detail)

ct2012-ct2013 (caption)

|

|

| |

Thomson was first and foremost a photographer and thus committed to methodologies that depended on the articulation of visual differences. His photographic practices bear this out. The cameo-sized images of the Pepohoan organize these subjects into a presentational format that provides an effective alternative to Lamprey and Huxley’s attempts to standardize photographs of ethnographic types. Thomson further enabled comparative visual analysis by capturing frontal, profile, and three-quarter views of his subjects. Even his larger photographs that take in the customs and dress of the Pepohaon retain these basic poses.

In discussing the origins of the Pepohoan people, Thomson’s caption also displays racist applications of the basic concepts of evolution circulating in England in the 1860s and 70s. I am not aware that there is throughout the island any trace of the woolly-headed negro tribes found in the Philippines, on the mainland of Cochin China, in New Guinea and elsewhere, and supposed by some to be the remnant of the stock from which the original inhabitants sprang.…The relationship between these islanders (i.e., the Pepohoan) to the hill-tribes of Eastern Asia would seem to point to that part of the world as the early home of the fair, straight-haired races who inhabit the islands from Formosa to New Zealand, and from Madagascar to Easter Islands. This theory would account for the total extinction of the negro race in the islands nearest the coast of China, as well as for the circumstance that they are still found in abundance in the remoter islands, such as New Guinea, where the negroes have been enabled to hold their own against such small numbers of pale invaders as would have been able to reach their shores. In the intermediate islands the blacks have been driven to the mountains and forests, and, in the north have disappeared entirely, and given place to the fairer and stronger race.

We see, then, in Thomson’s practices, inclinations and tendencies that subsume contemporary issues and debates circulating in Britain’s learned societies. It is thus fitting to ask what Illustrations of China and Its People may have contributed to these debates. No documentation or testimony survives to link Thomson’s China photographs and the practices they embody to the policies of the societies to which he subscribed. However, Thomson framed Illustrations of China and Its People as a travel narrative, stating in the introduction to volume one: “I hope to see the process which I have applied adopted by other travellers.” Perhaps the Royal Anthropological Institute’s 1874 publication Notes and Queries on Anthropology, for the Use of Travellers and Residents in Uncivilized Lands bears the stamp of Thomson’s achievements. The Royal Geographical Society issued a similar publication in 1883 titled Hints to Travellers. In his essay on anthropology, E. B. Tylor, one of the contributing authors to this publication, recommended the use of photography to record native types.

Exploring the Yangzi River

Thomson’s use of ethnology to frame the photographs of his travel to Formosa has a corollary in his 1200-mile journey up the Yangzi River. The 19 images grouped under the title “From Hankow to the Wu-Shan Gorge, Upper Yangtsze” and accompanying text offer another sub-narrative informed by imperialist discourses circulating in British learned societies. But whereas his study of Formosa’s Pepohoan natives was framed by ethnological discourses, Thomson’s Yangzi River narrative exhibits a combination of scenic views and types more in keeping with expeditions supported by the Royal Geographical Society.

Thomson’s scenic views of the Yangzi gorges constitute some of his most picturesque images. His descriptions of these scenes are particularly attentive to aesthetic experiences his photographs captured. His views of the Mi-Tan Gorge and T’sing-tan Rapid exemplify these concerns. Describing the former, Thomson wrote:

This rapid is one of the grandest spectacles in the panorama of the Upper Yangtse. The water presents a smooth surface as it emerges from the pass. Suddenly it seems to bend like a polished cylinder of glass, falls eight or ten feet, and then, curving upwards in a glorious crest of foam, it surges away in a wild tumult down the river.

His photograph of the Wu-shan Gorge carries this caption:

The river here was perfectly placid, and the view which met our gaze at the mouth of the gorge was perhaps the finest of the kind we had encountered. The mountains rose in confused masses to a great altitude, while the most distant peak at the extremity of the reach resembled a cut sapphire, its snow lines sparkling in the sun like the gleams of light on the facets of a gem. The other cliffs and precipices gradually deepened in hue until they reached the bold lights and shadows of the rocky foreground.

In these passages, Thomson draws attention to the superlative visual sensibilities he captured in these photographs, and in this sense his presentation of the Yangzi River images differs little from the approach he adopted for his photographs of China’s historic architecture.

|

|

| |

Scenic Views of the Upper Yangzi

Thomson’s Yangzi River narrative exhibits a combination of scenic views and types more in keeping with expeditions supported by the Royal Geographical Society. His views of the Yangzi gorges are some of his most picturesque images.

|

|

| |

“The Mi-Tan Gorge, Upper Yangtsze”

plate XXI, no. 48, volume 3

ct3104

|

|

| |

“The Tsing-Tan Rapid, Upper Yangtsze”

plate XXII, no. 49, volume 3

ct3106

|

|

| |

“The Lu-Kan Gorge, Upper Yangtsze”

plate XXIII, no. 50, volume 3

ct3108

|

|

| |

“The Wu-Shan Gorge, Upper Yangtsze”

plate XXIV, no. 51, volume 3

ct3110

|

|

| |

While passages highlighting the picturesque qualities of the Yangzi provide a conceptual link to the scenic views scattered throughout Illustrations of China and Its People, they are few and far between, for Thomson significantly altered his protocols for the Yangzi River segment of his travels. He abandoned the usual image/caption combination in favor of a single lengthy caption in which he makes only passing references to the photographs. His scenic views are subsumed by a narrative emphasizing movement along the river above all other considerations. Clearly, Thomson regarded this segment of his travels as deserving of special treatment. So how might we understand this shift in protocol?

Noting similarities with David Livingstone’s 1854 to 1856 exploration of the Zambezi River in Africa, James Ryan suggests that Thomson’s Yangzi River journey typifies the sort of exploration promoted by the RGS. 9 To the Zambezi expedition we could add Sir Richard Burton’s discovery of Lake Tanganyika in 1858, Livingstone’s search for the source of the Nile between 1866 and 1871, and Henry Morton Stanley’s navigation of the Congo River from its source to the sea between 1874 and 1877. Founded in 1830 and chartered by Queen Victoria in 1859, RGS expeditions were undertaken in the spirit of exploration and discovery. Newspapers such as the Daily Telegraph and the New York Herald sometimes provided financial assistance in the hopes of increasing circulation with vivid accounts of intrepid explorers opening up remote regions of the globe. But while tales of adventure in distant lands made for sensational headlines, RGS expeditions were also and more importantly intended to serve British imperialist interests. Successful navigation of Africa’s rivers enabled extraction and exploitation of the continent’s vast natural resources.

Circumstantial and written evidence suggests Thomson’s Yangzi River journey is best understood from the perspective of RGS expeditions. He became a member of the RGS in 1867 during his brief visit to Britain prior to taking up residence in China. And although there are no surviving accounts of his activities and associations within the RGS at that time, past and pending expeditions were well documented in RGS publications as well as the popular press. While organizing his photographs and authoring captions for Illustrations of China and Its People after his return to Britain in 1872, Thomson delivered a lecture on his Yangzi expedition to the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS), an umbrella organization that drew its membership from several learned societies.

His findings were subsequently published as “The Gorges and Rapids of the Upper Yangtsze” in the 1874 edition of the BAAS’s annual report. More specifically, the narrative Thomson supplied for his Yangzi journey betrays the hallmarks of RGS concerns. As Ryan notes, much of Thomson’s Yangzi River narrative focuses on the potential for steam-vessel navigation of the Yangzi in order to open up the interior of China to commerce. 10 He addresses navigational hazards, potential sites for trade depots and foreign settlements, and at one point along the lower Yangzi, he even advocates constructing a canal to cut 22 miles off the journey.

In serving Britain’s imperial projects, RGS expeditions were concerned with far more than just topography and the prospects of resource exploitation. The RGS regarded itself as a scientific organization charged with the acquisition of knowledge broadly defined to include botany, zoology, mineralogy, and the study of indigenous peoples and cultures. Well-financed expeditions often included personnel dedicated to the acquisition of specimens, and where indigenous peoples were concerned, photography provided the means to this end. 11 Thomson’s Yangzi River narrative needs to seen from this broader perspective, in that his photographs include as many human types as scenic views. As with most RGS expeditions, the people he encountered were an important component of his assessment of the river’s potential for commercial exploitation. Thomson’s photos and commentary betray these RGS sensibilities with an interesting mix of specimen acquisition, ethnological curiosity, and a utilitarian view of the river’s human resources.

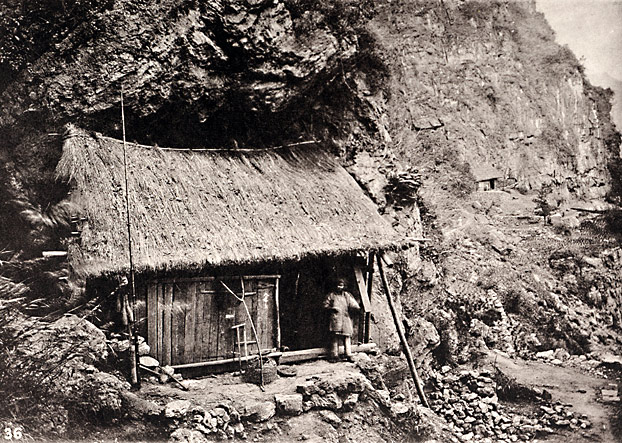

Upon entering the I-Chang Gorge, the first of several hazardous rapids along the upper Yangzi, Thomson began recording his observations of life along the river. He noted the “rude fisher-huts, perched here and there upon the lofty cliffs” as he passed through the steepest parts of the gorge. Where the river widened briefly, he discovered “several houses of a better class, surrounded by patches of orchard ground,” the inhabitants of which “obtained a livelihood by selling the produce of their gardens to the passing boats.” He then passed by more primitive dwellings, which he photographed and commented on as follows: To these more civilized dwellings there succeeded abodes of a most primitive type—cave hovels, closed in front with a bamboo partition, and fitted with doorways of the same material. These cabins were erected in the most inaccessible positions beneath overhanging cliffs, and their smoke-begrimed interiors reminded me of the ancient cave dwellings which sheltered our forefathers at Wemyss Bay in Scotland.

|

|

|

| |

“Cave Dwellings, I-Chang Gorge, River Yangtsze,” plate XVIII, no. 36, volume 3 ct3085 (caption) ct3087 (photo)

|

|

| |

The comparison Thomson invokes here positions the inhabitants of this section of the river on a lower order of civilization. But he also recognizes the potential of this human resource.

It is in just such desolate spots as these that the frugality and industry of the Chinese race are most conspicuously exhibited.

Thomson ends this passage by noting that stone from the I-Chang Gorge “used for building and for embankments lower down the river is found in great abundance.” The implications seem obvious: this section of the Yangzi offers a highly useful resource (i.e., stone for building) in close proximity to primitive, frugal, and industrious (i.e., exploitable and cheap) labor.

With the potential for steam-vessel navigation of the Yangzi being Thomson’s primary concern, his photos documenting coal extraction accord well with RGS interests in natural and human resources. His description of Chinese coal mining, rife with comparisons with British methods, suggests a desire to make the process more productive and profitable. For a photo showing a mine he writes: There are a number of coal mines near Patung, and in the rocks where the coal-beds are found the limestone strata have been thrown up from the stream in nearly perpendicular walls. The coal is slid down from the pit’s mouth to a depot close to the water’s edge, along grooves cut for that purpose on the face of the rock. The workings are usually sunk obliquely, for a very short distance, into the rock, and are abandoned in places where to our own miners the real work would have barely begun. They sink no perpendicular shafts, nor do their mines require any system of ventilation.

Thomson’s comment accompanying two photos of Chinese miners highlights their low wages. He notes that men who extract the ore “average 300 cash a day, or about seven shillings a man per week,” while porters who carry ore in creels attached to their backs “can earn two hundred cash a day.”

|

|

|

|

| |

“Coal Mine,” plate XIX, no. 42, volume 3

ct3091 (caption) ct3095 (photo)

“Chinese Coal Miners,” plate XX, no. 44, volume 3

ct3097 (caption) ct3099 (photo)

|

|

| |

Young children were employed to manufacture fuel by casting a mixture of coal with water in moulds that were then dried in the sun. Remaining attentive to the economic potential of coal extraction, Thomson notes that each block weighed one and one-third pounds and sold for five shillings a ton. He concludes his assessment of coal production by citing the observations of a predecessor:Baron von Richthofen has assured us there is plenty of coal in Hupeh and Hunan, and that the coal field of Szechuan is also of enormous area. He further adds that at the present state of consumption the world could be supplied from Southern Shasi alone for several thousand years, and yet, in some of the places referred to, it is not uncommon to find the Chinese storing up wood and millet stalks for their firing in winter, while coal in untold quantities lies ready for use in the soil just under their feet. The vast coal-fields will constitute the basis of China’s future greatness, when steam shall have been called to aid her in the development of her inland mineral resources.

|

|

|

|

| |

“Making Fuel,” plate XIX, no. 43, volume 3

ct3091 (caption) ct3096 (photo)

“Drying Fuel,” plate XX, no. 45, volume 3

ct3097 (caption) ct3100 (photo)

|

|

| |

When seen from this broad perspective, Thomson’s images of coal production and his Yangzi River types in general retain their ethnological sensibilities while functioning as integral components of his broader concerns with navigation and exploration in service of British interests.

While utilitarian and imperialist in conception, RGS expeditions were presented to the public as adventures undertaken with considerable difficulty in distant and often dangerous places. Their retelling, in print or in person, exploited suspenseful incidents ripe with the possibility of imminent demise in order to enhance the daring heroics of their principal characters. Thomson possessed a keen awareness of these narrative tropes, and made effective use of them his Yangzi River tale.

Foreigners were uncommon in the interior of China and sometimes viewed with suspicion or hostility. Thomson recounts a couple of shore-leave excursions that he perceived as threatening, but pirates were the main concern. He and his two American traveling companions often stood watch in shifts throughout the night. Relating one such experience, Thomson wrote:I spent the time in writing letters, with my revolver close at hand. Once thinking that I could hear whispering and a hand upon the window, I grasped my pistol, and made up my mind to have a dear struggle for life. Listening, I heard the heavy breathing of the men piled in a sleeping mass in the forehold, and unconscious that a scene of bloodshed might the next moment ensue; then there was a noise in the cabin; and at last appeared my companion to relieve me on the watch. He had himself been the author of my unfounded alarm.

|

|

|

| |

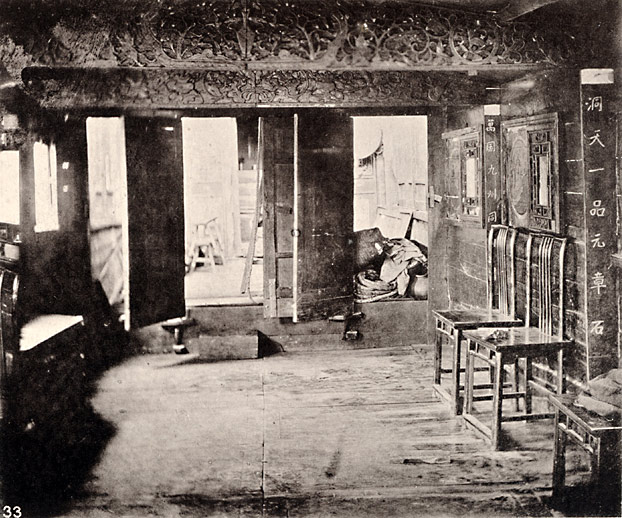

“Interior of Native Travelling Boat,” plate XVII, no. 33, volume 3

ct3075 (caption) ct3072 (photo)

|

|

| |

This brief but suspenseful story of a night early in the journey serves to set up a far more dangerous event that occurred later among the gorges upriver. The officers of a gunboat stationed at the boundary which parts Hupeh from Szechuan warned us to beware of pirates, and they had good reason for so doing. The same night, at about ten o’clock, an intense darkness having fallen upon the gorge, we were roused by the whispering of a boat’s crew alongside us. Hailing them we got no answer, and we therefore next fired high, in the direction whence the sound proceeded; our fire was responded to by a flash as report from another direction. After this we kept watch during the entire night, and were again roused at about two o’clock to challenge a boat’s crew that was noisily stealing down upon our quarters. A second time we were forced to fire, and the sharp ping of the rifle ball on the rocks had the effect of deterring further advances from our invisible foe.

RGS expeditions in remote areas relied on local guides, interpreters, and labor. These circumstances provided opportunities for close study of the habits, character, and social interactions of indigenous people. Thomson’s Yangzi expedition was similarly equipped. He hired a translator and two boats with crews to carry him up the Yangzi. Living in close proximity with his hired help led Thomson to comment on their character and appearance. Of the crew, he wrote:

These people can hardly be said to go to bed,—they wear their beds around them. Their clothes are padded with cotton to such an extent, that, during the, day they look like animated bolsters. They never change their clothes, oh no! not until winter is over; and then they part with the liveliest company in the world. The boatmen are a miserably poor lot; nine of them sleep in a compartment of the hold about five and a half feet square, and disagreeable indeed is the odour from that hold in the morning, for the boatmen keep the hatches carefully closed and smoke themselves to sleep with tobacco or opium, according to their means and choice.

|

|

|

| |

“Boat’s Crew at Breakfast,” plate XVII, no. 34, volume 3

ct3075 (caption) ct3073 (photo)

|

|

| |

Thomson expressed similar displeasure with his interpreter Chang (depicted below) who, while educated, could not understand the dialect spoken by the crew. However, he redeemed himself as a master of ceremonies when Thomson met local officials along the route. Thomson’s intimate studies of his crew serve as ethnology, but they also enliven his narrative with humorous anecdotes of shore leaves comprised of “drinking, gambling, and opium smoking,” cock sacrifices to the river god, disputes between the crew and captain, disputes between the captain and his strong-willed wife, and several accounts of interpreter Chang’s quirky behavior.

| |

| |

“Our Chinese Interpreter,” plate XVII, no. 35, volume 3

ct3075 (caption) ct3074 (photo)

|

|

| |

Although Thomson’s Yangzi River journey received no official support or funding from the RGS, his images and commentary clearly conform to RGS discourses during the great age of river exploration. As with his study of Formosa’s Pepohoan tribes, the Yangzi River segment of his travels reveals the impact of Britain’s learned societies on both his photographic and narrative practices.

| |

|