| |

Hope

|

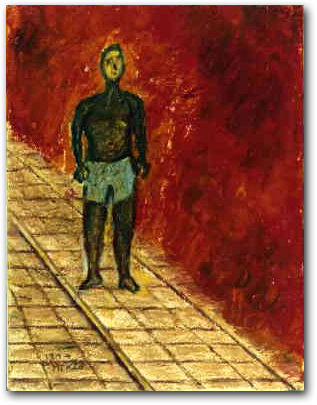

It may seem difficult to look at these pictures of hell on earth and emerge with hope, but that is presumably what many of the survivors who drew them intended. One picture that was accompanied by a long explanation addressed this directly. The artwork itself depicted a man wearing nothing but shorts, standing by a wall of fire. He was the artist's neighbor, a professor who had been unable to save his trapped wife from the flames. They had been eating breakfast when the bomb fell, and he still held a ball of rice (onigiri) in his hand.

"But I wonder how he came to hold that rice ball in his hand," the artist wrote at the end of his commentary. "His naked figure, standing there before the flames with that rice ball looked to me like a symbol of the modest hope of human beings."

|

|

A university professor whose wife has been consumed by the fire stands stunned by the streetcar tracks, clutching a ball of rice in his hand. A university professor whose wife has been consumed by the fire stands stunned by the streetcar tracks, clutching a ball of rice in his hand.

INOUE Mikio

40 years old in August 1945

[14_08]

|

It is this modest hope that helps explain why so many survivors eventually responded to the invitation to share what they personally experienced and witnessed in August 1945. Grief and hope together underlie the philosophy that has developed around Hiroshima and (to a lesser extent) Nagasaki. This is conveyed in the famous lines by the poet Tōge Sankichi that are carved (in English as well as Japanese) on a monument in the "peace park" in Hiroshima:

Give back my father, give back my mother;

Give grandpa back, grandma back;

Give me my sons and daughters back.

Give me back myself.

Give me back the human race.

As long as this life lasts, this life,

Give back peace

That will never end.

Tōge was a survivor who died in 1957, at the age of 36, from leukemia caused by exposure to the bomb's radiation. His poem is titled "Give Back the Human."

In more abrupt, political language, the intent behind such remembrance has been compressed into the simplest of slogans: No More Hiroshimas. What the artwork is intended to do is remind present and future generations of the intimate human experience behind such sloganeering.

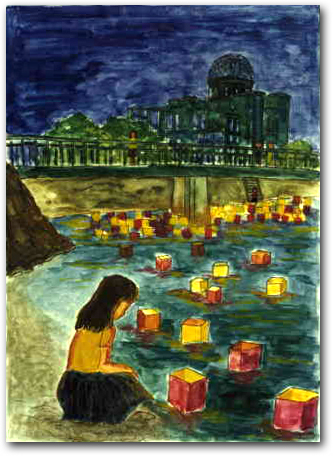

As it happens, there is a serendipitous convergence between the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 and traditional Japanese commemoration of the souls of the dead. The Japanese "All Souls Day" is known as Ōbon, and falls either in mid-July or mid-August depending on whether one follows the old (lunar) or new (solar) calendars. Both dates are still observed in Japan, and the practice is both solemn and celebratory. The dead are welcomed back to earth with folk dances and other community activities. When time comes for them to return to the other world, they are seen off late in the evening by floating square paper lanterns lighted with candles on the rivers.

Memorialization of the victims of the atomic bombs overlaps with traditional Ōbon observances. Perhaps because of this (or perhaps the overlap of the calendar is just coincidence), it has become customary in Hiroshima and other places throughout the world to remember the victims of the 1945 bombs by floating lanterns. Usually each participant paints pictures or words on one of them. These are simultaneously prayers for the souls of the dead and prayers for peace.

In Hiroshima, the floating of these lanterns has poignancy beyond the city's experience in August 1945, for the beautiful lighted lanterns are floated on the very same rivers that once were clogged with corpses.

Tucked among the survivors' pictures in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, without any explanation, is an amateur painting of these floating lanterns, with Hiroshima's famous, unreconstructed city-hall dome visible against the evening sky. The brief caption that came with this reads "The lanterns floated and prayers lifted up for the peaceful repose of the A-bomb dead and for peace."

The artist was a young woman born 11 years after the end of the war. She was 18 when, in 1974, she responded to the invitation to draw personal memories of the bomb.

|

Floating lanterns as a prayer for the souls of the dead and a prayer for peace. The artist was 18 years old in 1974 when she responded to the appeal for pictures recalling the bomb. Floating lanterns as a prayer for the souls of the dead and a prayer for peace. The artist was 18 years old in 1974 when she responded to the appeal for pictures recalling the bomb.

TAKASHIBA Harue

Born in 1956

[17_30]

|

|

|

|