| |

DRAMA AND THE CITY

Rebecca Nedostup

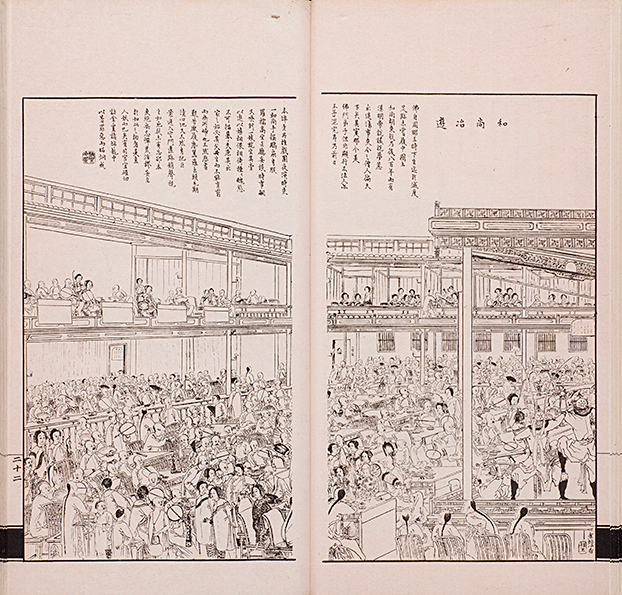

Two iconic artists, two arresting images, two ways of depicting drama for the eyes of the late-19th-century Shanghai public: Wu Youru puts one of his beloved Western sailing ships in the company of a dragon, marrying the marvel of new technology to the spectacle of the numinously powerful; and Jin Chanxiang, artist of social detail and the ladies’ quarters, uses the story of a monk misbehaving in the pleasure districts of Shanghai as a prop for a fabulously detailed rendering of one of the mainstays of entertainment and urban life—the opera theater, with its myriad denizens.

|

|

| |

One illustration invites the viewer to draw back in wonder, the other to peer in close and pick out every facial expression, gesture, and implied joke. Beyond the surface, though, both strike at the heart of the epistemological battles of their time.

|

|

| |

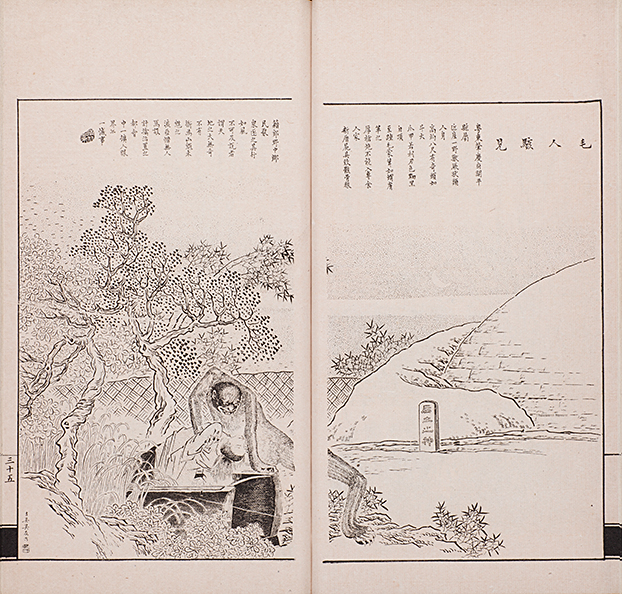

“Westerners Sight a Dragon”

|

|

| |

Wu Youru’s illustration invites the viewer to witness a witnessing: proof of the meeting of new and old knowledge, teased in the headline “Westerners Sight a Dragon.” The text sets up the opposition—whereas writing on dragons has been so commonplace in China since ancient times that one barely has to cast a glance at any library to find something on the topic, “later people” have put more value in Westerners and their scientific method as a measure of existence and truth. Yet Western-language newspapers have recently told an account of a steamship off the southern coast of Africa whose crew encountered an enormous whirlpool in a storm, which they reckoned could only have been made by an enormous fish. Some caught a glimpse of a tail that was no less than 20 feet long, and others swore that the body under the roiling waters had to be 100 feet at least. But since they were able to collect no physical proof, no one believed them.

|

|

| |

Such a thing would never happen to Chinese people, the Dianshizhai writer scoffed, because they would know that such a powerful thing was a dragon, and that a dragon, by its very nature, was shape-shifting and imperceptible in the storm. It is no good to make things out as strange simply because they are unfamiliar, he concluded. In this writing, the encounter was not simply one of man and beast, but of ways of knowing. As Rania Huntington wonderfully writes, it also posits “the seas as a realm of the strange open to both Chinese and Western observers.” [1]

Wu depicts this battle of knowledge systems in visual terms. The powerful dragon in the foreground—so long it cannot be contained in the frame—captures all the drama, and is rendered, along with the waves that surround it, in a style more familiar to those who had visualized dragons through woodblock prints and ink painting. For once one of Wu’s beloved steamships is in the background of the visual story. To this he adds a narrative fillip not in the original account: the Western ship is on the verge of being capsized by this very Chinese-looking dragon in an African sea.

|

|

| |

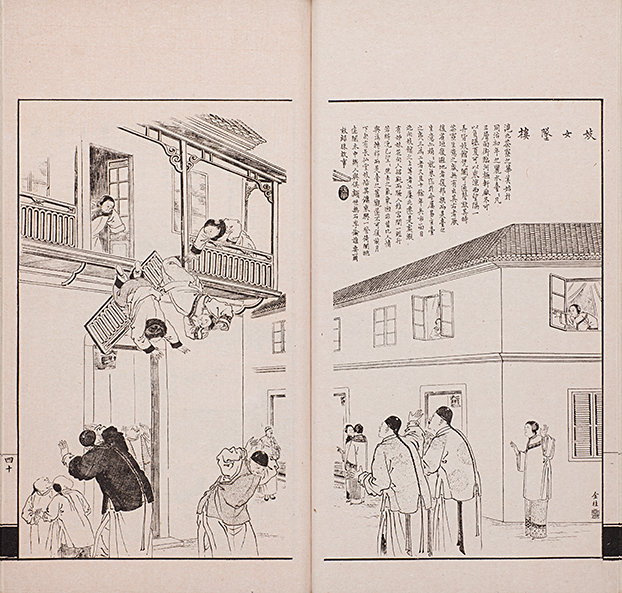

“Monk Engages a Courtesan”

|

|

| |

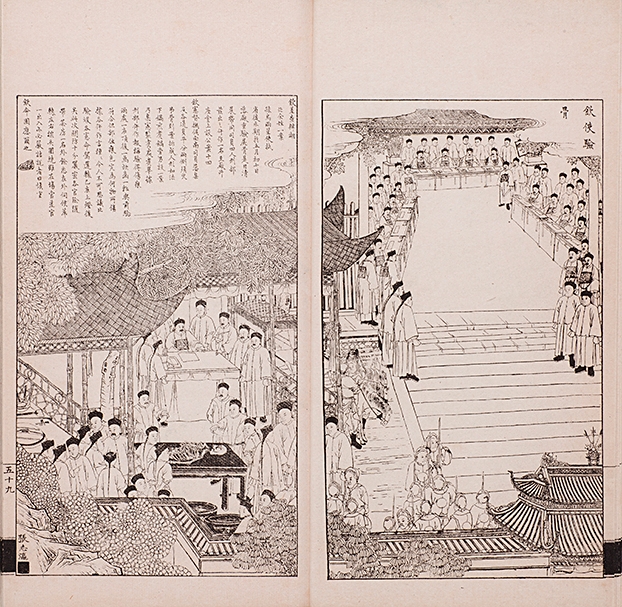

The story that Jin Chanxiang and his writer are telling is quite different, though equally entertaining. The text tells the tale of a monk who made an appearance at the Shanghai’s Laodangui Theater and spent the evening playing host to the prostitutes he knew to be found there. While the writer takes this opportunity to launch an attack against the mendacity and untrustworthiness of the country’s Buddhist clergy, Jin Chanxiang grabs a chance to provide his audience sheer visual overload.

Here near the bottom center, indeed, is the monk surrounded by women, who have in turn attracted another layer of male attention. But we can pick out a wealth of other detail: individualized persons, the relative affluence of the male and female spectators on the second floor gallery, and the onstage action. So although the text reveals a culture war about religion that was being fought partly in the pages of the Dianshizhai, audiences unconcerned with this sort of moralizing could revel in the details and drama of the theatergoing urban crowd. [2]

|

|

|

|

Looking at the rich detail in “Monk Engages a Courtesan”

(和尚冶游, 1884 yi, artist Jin Chanxiang), we observe a monk surrounded by women (bottom left); individualized persons such as a man with a beard (middle) and another in the gallery wearing sunglasses (top); the relative affluence of the male and female spectators on the second floor gallery (top); and the onstage action (bottom right).

[View caption & English translation]

[dz_v11_023] |

|

| |

The Dramatic and the Strange

These kind of illustrations built on a narrative genre that would have been familiar to readers and listeners in 19th-century China: the “tale of the strange” (zhiguai). Canonized in collectanea like the ealy Qing writer Pu Songling’s Liaozhai zhiyi (Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio), zhiguai tales addressed everything from ghosts, fox spirits, and enlightened beings to the anomalies of the natural world. They remain fertile source material for film, manga, and anime adaptations today.

In a similar fashion, Dianshizhai artists and writers saw both how their new medium could depict old stories in a new way, and how they could mold breaking news by melding the sensibility of the zhiguai genre with the detailed and shocking visuals of lithography. Rania Huntington notes that as they did in zhiguai, stories of the odd and dramatic in the Dianshizhai and its parent paper Shenbao emerge both to instruct and to give pleasure to the reader. But now these tales encompass the potential strangeness of the entire globe, accompanied by panoramic visualizations on a scale beyond that of the occasional illustrations in zhiguai compilations.

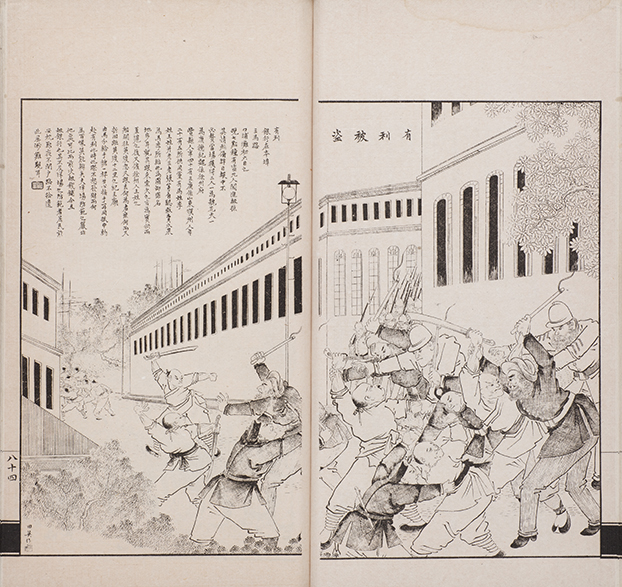

Unsurprisingly, strange subjects ranged widely. Artists introduced the curiosities of far-away worlds; not only did they depict the past as well as the present of the West, but they could now render the ancient past of China at a new level of granularity. They pictured and explained oddities from various corners of the Qing empire, and from the coastal networks through which the Dianshizhai writers operated. And they used the artistry afforded by the lithograph to depict crimes and other lurid events with great drama and emotion. Thus, like the crowd scenes in previous chapters, the crime scene became a new sub-genre unto itself. It may not have depicted the fantastical on the order of gigantic fish or miniscule humans (both of which appeared in the pages of the Dianshizhai), but in sensationalism and entertainment it was their kin. [3]

|

|

| |

“Robbery of the Chartered Mercantile Bank”

|

|

| |

Thus, in a dramatic story of a robbery of a foreign bank near the Bund, the drawing is all about a vivid battle between the thieves and the multinational police force (British, Sikhs, and Chinese gendarmes). The battle is never mentioned in the text, which concentrates on the motives and guilt of the robbers, and the crime’s implications for the safety of Shanghai’s citizens. The text provides moral arbitration for the benefit of a literati audience. The illustration services those who just want to see a good fight (one in which some of the malefactors even seem to get away).

|

|

|

| |

“Robbery of the Chartered

Mercantile Bank”

有利被盜

1886 xin (Vol. 12, p. 36)

artist Tian Yingzuo

Yale 12.037 [dz_v12_037]

Translated caption:

“The Mercantile Bank is located on Third Road near the Bund. At seven o’clock on the sixth day this month, nine robbers broke into that bank. Our newspaper [i.e. Shenbao] has reported the details, which will be omitted here. Two robbers were caught on spot: Wei Huatian and Kang Deji. Wei, forty-three years old, was from Feng county in Xuzhou district, Shandong province; Kang, twenty-five years old, from Pu district, Shandong province. ...”

[View caption & English translation] |

|

| |

It was not always the case that the text of Dianshizhai stories presented the “facts” and the illustration the “fancy.” Very often the two worked together in a collaboration of imagination and chronicle. Sometimes news items merged with tropes and images from the historical record of China and the world.

|

|

| |

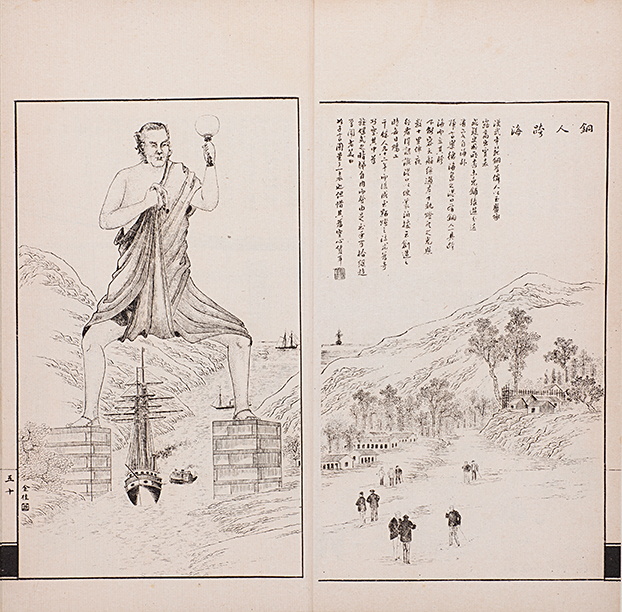

“Bronze Figure Bestrides the Strait” |

|

| |

The story is clearly meant to refer to the Statue of Liberty, completed in 1886, indeed after 12 years of labor. But the piece and the illustration were also obviously done in advance of visual evidence of the New York monument, so writer and artist likewise drew upon the Western feat of marine monumentality that was in their reference bank: the Colossus of Rhodes. In order to suit the times, however, artist Jin Gui marries the visual conventions of the Colossus—the figure, standing on plinths, astride a narrows with a ship passing underneath—to indicators that spoke “Western modernity” to Shanghai viewers of the 1880s. The ships are steam vessels; the light resembles an outsize version of the kerosene lamps imported to China in the 19th century; and the Colossus himself sports florid sideburns.

|

|

|

|

“Bronze Figure Bestrides the Strait”

銅人跨海

ca. 1887 (Vol. 16, p. 2)

artist Jin Gui (Jin Chanxiang)

Yale 16.003 [dz_v16_003]

Translated caption:

“Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty once cast a bronze figure that was higher than the clouds and used a jade plate to hold the dew. Many have doubted the authenticity, or possible exaggerations, of this historical account. Lately, a traveler returning from abroad said that, at the port of Rhodes, there is a bronze figure standing over the strait, and that huge vessels can pass easily between his legs. ...’”

[View caption & English translation]

Translated by Flora Shao

|

|

| |

“‘Intercalary Fish’ Emerges

from the Sea”

|

|

| |

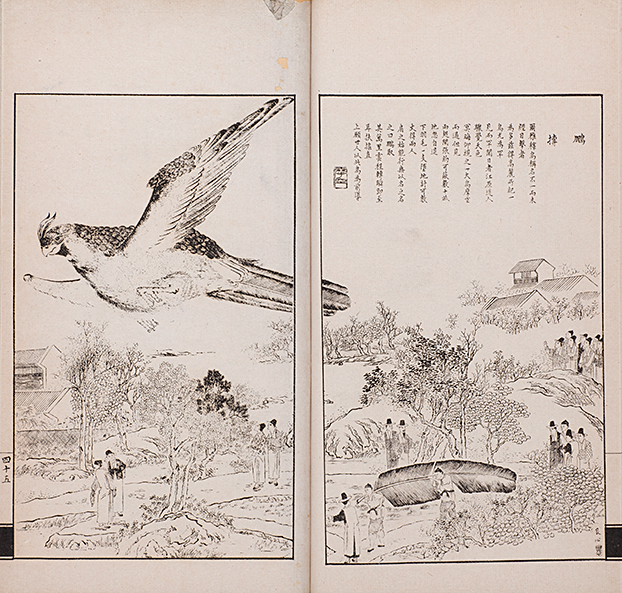

The fantastical offered an opportunity for oblique comment on politics both local and global. Thus the tale of the “Fish-Bringing Storm” in Tiangang, by the sea near Yancheng, some 200 miles north of Shanghai, conveyed a moral about the Dianshizhai’s obsession—marine power. In that place, readers were told, a violent summer storm had churned forth a giant glimmering fish. Artist Tian Ying depicts its fate. The local magistrate has arrived with a retinue in order to ritually mark the occasion (propitiating either the fish itself or the marine deity who produced him amid the storm), while villagers wait with knives and baskets to butcher the beast. One even sharpens his cleaver on a rock.

|

|

| |

The text notes that people found the fish to be both tasty and, judging from its bones, very old and coined the localism “fish-bringing storm” to describe the kind of weather that produced it. This was hardly an auspicious development in the author’s eyes. Once was the day, he wrote, when boats would vie with one another to harvest the oceans. Now, he lamented, the dynasty was so weak and power in the seas so reduced that such a kind of monster could grow undisturbed.

Flights of Fancy

Sometimes the curiosities in the pages of Dianshizhai were simply wonderful, in all senses of the word. Magical happenings from the past and the present were plucked from the social atmosphere to provide the audience with new marvels along comfortingly familiar lines, and a context in which to place the wonders of new technology. Tales of marvelous animals, for instance, gave Dianshizhai illustrators an excuse to spread their wings, showing viewers images of classical creatures they may have only previously encountered in the telling. Flight was an especially evocative way to link the past and the present.

|

|

| |

“A Great Beginning (A Flying Roc)”

|

|

| |

Here, news of a giant bird sighted in Korea (each single feather so large it took two men to move it) is linked to a tale from the Chinese canon. “Since the bird has no name, [we] will call it Peng,” the author says, referring to the majestic creature whose description so memorably opens the Zhuangzi. [5]

|

|

|

|

“A Great Beginning (A Flying Roc)”

鵬搏

ren 1884 (Vol. 13, p. 45)

artist (Fu) Genxin

[View caption & English translation]

Yale 13.046 [dz_v13_046]

The headline puns on a well-known phrase, pengtuan, meaning “a great beginning” but literally deriving from the words “the Peng takes off.”

|

|

| |

“Huge Bird Carries a Man

into the Air”

|

|

| |

For a story closer to home (this in Zhili province in the north of China), another artist depicts a similar bird in struggle with an intrepid man who dared to investigate the source of strange noises coming from the top of a famous local pagoda.

|

|

| |

“Bird Wings on A Human Body”

|

|

| |

Overall, flying was more often wondrous than fearsome in the pages of the Dianshizhai, as the image of the transformative Peng attests. In another story, this one about mechanical flight, the writer comments that all the subsequent generations who marveled at Mozi’s (ca. 479-381 BCE) reputed invention of an avian automaton and thought it strange “ignored the human spirit,” which would come up with more and more ingenious ways to take to the air. |

|

| |

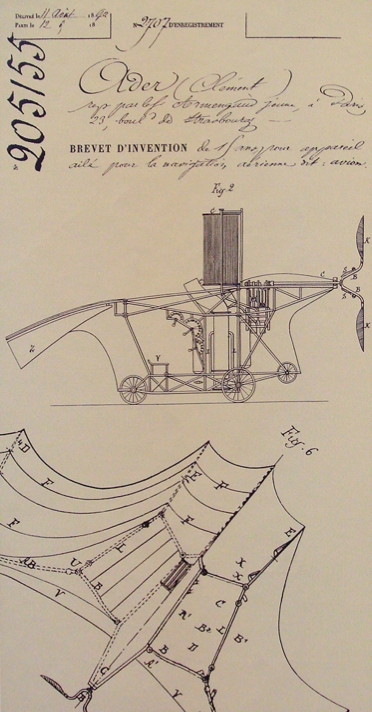

The news item and accompanying illustration describe the exploits of the French inventor Clément Ader (1841-1925). The reference is likely to Ader’s 1890 test flight of the “Éole,” a steam-driven propeller craft with wings modeled on those of bats. He continued to work on other prototypes, and in 1897 tested the French Navy financed “Avion III,” which is today housed in the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris.

|

|

| |

The thoroughly charming illustration shows the same facility with expressions and emotions that Jin Chanxiang displayed in “Monk Plays the Field,” the wonder and excitement of Ader’s observers on the ground is met with satisfied calm from the man himself.

| |

|

Clément Ader

French patent 205155,

Avion (a.k.a. “Éole”

April 19, 1890.

[wikipedia] |

| |

Bodily Evidence

“The strange” was a capacious category that permitted worry as well as whimsy; that is what made it such a useful social barometer. The technological and social changes that allowed for the wonders of flight and underwater exploration also demanded dizzying changes in the conception of self all the way down to basic ideas about bodily comportment and the integrity of the human form. Dianshizhai authors and artists frequently portrayed cultural shifts in the form of curiosity and caution about the body and bodies in stories about medical innovation, strange humanoids, and the proper treatment of the dead.

Often these expressed the nascent debate between Western biomedicine and Chinese medical theories and treatments. In essence, what we receive through the Dianshizhai items on Chinese-Western bodily conflict is a set of Chinese views on a perceived cultural difference that has been much more often portrayed, in words and in images, from the Western perspective (i.e. missionary and foreign observer preoccupation with punishments, queues, footbinding, and infanticide, fixations that have their current descendants in mass media fascination with tales of Chinese suffering). [6]

As in many late-19th-century media outlets around the world, the perspectives in the newspaper on such topics ranged from the learned to the ill-informed. There were many times when body horror in the Dianshizhai simply drew on extant tropes from popular culture and tales of the strange, not to dive into a cross-cultural debate, but to give expression to historically specific or generalized anxieties.

|

|

| |

“Chinese & Westerners Help the Helpless”

|

|

| |

The Dianshizhai authors were advocates for gradual medical change in the hands of learned men. Here Jin Chanxiang illustrates the story of a Shanghai doctor who, finding his own son grievously injured and himself mentally incapable of treating him, entrusts the young man’s life to the hands of a Western physician, “Shengde.” The son recovers, and so impressed is the father by the capabilities of Western treatments and by “Shengde”’s generosity that he knows he can bring him the city’s impoverished sick for care.

|

|

| |

“Imperially Dispatched to Examine Bones”

|

|

| |

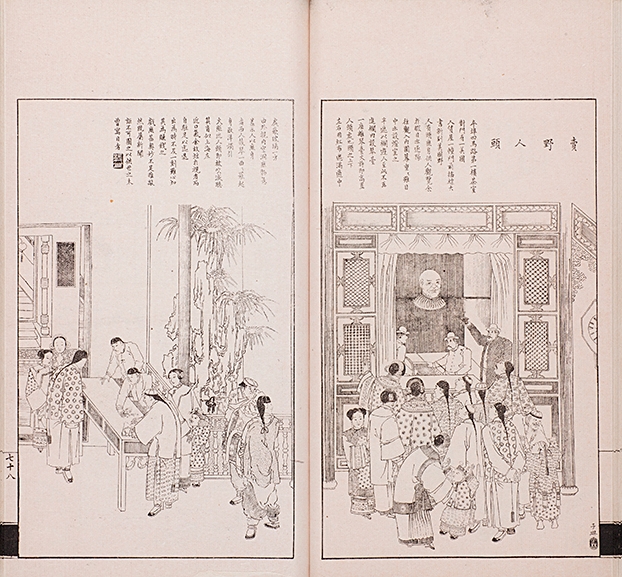

Dianshizhai artists did not shy away from exciting their viewers by depicting the human body in extremis; the message that accompanied these illustrations could vary. This 1884 rendering of a criminal investigation has in reproduction become one of the pictorial’s more famous images.

Though the eye is immediately drawn to the skeleton on the table, the key to the illustration and the text is the forensic examination that surrounds it as a whole. Notably, the bones being examined (exposed by the “steaming method” described briefly in the text) take up a small portion of the legal spectacle of the entire illustration. [7] Similarly, the text describes this forensic method as a means by which the presiding officials discover evidence of two massive blows upon the body of the deceased, one Yu of Hebei. The excitement of the piece is very much that of a detective story: after this early morning discovery, “all was very secretive,” and officers were sent to arrest a servant from a local teahouse.

|

|

|

|

“Imperially Dispatched to Examine Bones”

欽使驗骨

1884 jia (Vol. 2, p. 10)

artist Zhang Zhiying

Yale 02.011 [dz_v02_011]

|

|

| |

Translated caption:

“Imperially Dispatched to Examine Bones.

In a recent legal case, imperial envoys investigated the corpse of a Mr. Yu in Hubei province: the two envoys Mr. Sun and Mr. Wu arrived at the province and opened a court session to examine the body and bones on the seventh day of the fifth month. On that morning, together with four bureau officials and a coroner from the ministry of punishments, the envoys arrived at the court and took their seats. ...”

[View caption & English translation]

|

|

| |

Six years later, the Pictorial ran a piece disapproving of a Western-style autopsy that was performed to determine the cause of death of a foreigner whose body was discovered in the Astor Hotel. [8] Especially when put in dialogue with “Imperially dispatched to examine bones,” it is clear that the objection was not to disassembly and examination of the body per se. Rather, the author saw Western techniques as crude, and moreover utilitarian (“so the body of the dead person is made use of, from the crown to the heel, in the interests of others”). [9] The suspicion that Americans and Europeans were eager to exploit the bodies of others for capitalist gain popped up regularly in the Dianshizhai, but many stories treated the theme with less outrage than amusement at the hucksterism of the times.

|

|

| |

“Viewing a Wild Man's Head”

|

|

| |

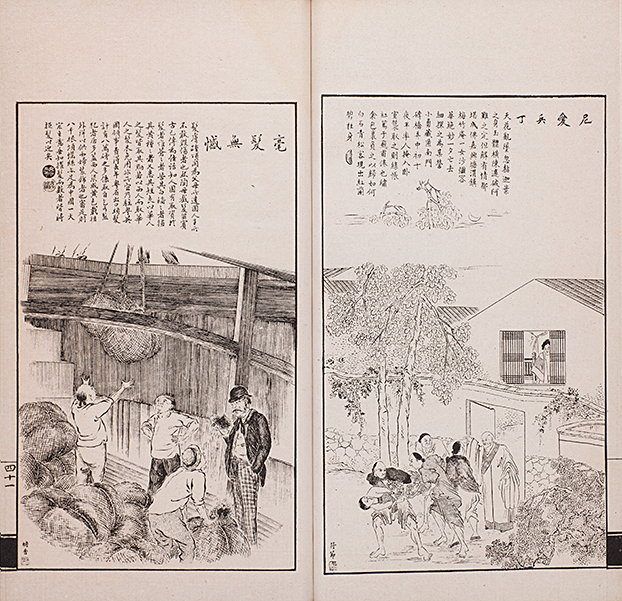

“Viewing a Wild Man's Head” (mai yeren tou 賣野人頭), the author explains, had quickly become Shanghainese slang for a swindle after an American had opened up a carnival act opposite a locally famous teahouse. [10] The text debunks the premise of the “talking head,” while the illustration depicts the accouterments of the act (such as the candle the “body-less” head is commanded to blow out). Though the author scoffs at the trick, he claims that being news, it should “be drawn for those in the world who haven’t seen it yet.” Artist Tian Zilin renders not just the trick, though, but the whole scene of the mini-carnival, from the oversized head and its barkers, to the varied audience members, and the comperes raking in cash at the door.

|

|

|

|

“Viewing a Wild Man's Head”

賣野人頭

1884 bing (Vol. 4, p. 29)

artist Zhang Zhiying

Yale 2.011 [dz_v04_031]

Translated caption:

“Viewing a Wild Man's Head.

An American gentleman has rented a house standing across the street from the Number One Teahouse on Fourth Avenue in Shanghai. A sign has been put up in front of the house which reads: Exhibited Here for the First Time Anywhere: The Disembodied Head of an American Wildman. ...

[View caption & English translation]

|

|

| |

“Not a Hair’s Breadth of Regret”

|

|

| |

Dianshizhai writers wryly observed that transnational commerce altered bodies in a number of startling and humorous ways. Citing a British consular report that English merchants had exported 80,000 pounds of human hair from Guangdong in the previous year, the text below observes that ancient taboos on preserving one’s hair as a parental legacy were contradicted by the knowledge that one could also make money off it.

What was the destination of the bundles of hair shown being lifted from the hold of a ship? Bleached and dyed blonde for European ladies’ ornaments—and, the author notes with some amusement, “most of [the hair] comes from beggars and criminals” (a claim made in horror in the original consular report). Here indeed was “a big piece of business for China.”

[11]

|

|

|

|

“Not a Hair’s Breadth of Regret” 毫髮無憾

1892 zhu (Vol. 15, p. 41)

artist Jin Chanxiang (Jin Gui)

[View caption & English translation]

Yale 15.042 [dz_v15_042]

The headline plays on a number of similar expressions such as “not the least bit (a hair’s breadth) of difference” (haofa wucha 毫髮無差).

|

|

| |

“The Shocking Sighting of a Sasquatch”

|

|

| |

Finally, there were times when the Pictorial writers and artists simply gave their viewers a good old-fashioned tale of the strange—only now they were illustrated with finesse and drama. Wu Youru’s lithograph for the account of a human-appearing animal that was desecrating graves in the Guangdong county of Kaiping is starkly beautiful and horrifying. Despite the headline, what would truly have been shocking to viewers would be the sight of an opened coffin, its occupant on display, however languidly.

|

|

|

|

“the Shocking Sighting of a Sasquatch”

毛人駭見

1886 geng (Vol. 9, p. 35)

artist Wu Youru

Yale 9.036 [dz_v09_036]

Translated caption:

“The Shocking Sighting of a Sasquatch.

The existence of a strange wild beast was recently reported in Kaiping county of Zhaoqing prefecture, Guangdong province. The creature is described as vaguely resembling a human being though some nine feet tall, with a massive oddly-shaped head and claws on its hands and feet as sharp as knives. ...

[View caption & English translation]

|

|

| |

“Female Ghost Demands a Life”

|

|

| |

More conventional in its visual narrative but hardly less thrilling is Jin Chanxiang’s depiction of the revenge of a wronged dead servant girl, who toppled her lascivious former master into a vat of boiling sugar syrup. Some viewers might have been thrilled; some might have quickly flipped the page and stashed the issue out of view.

|

|

| |

Dangerous Women and Undue Devotions

An urban milieu that encouraged social mixing across gender and class lines, against an increasingly transnational economic backdrop that encouraged entrepreneurialism verging on charlatanism, brought worry as well as excitement to the largely Confucian-educated men who wrote the Dianshizhai. Some of the things they saw around them had long concerned men of their station, such as women increasing their public presence outside of the household, or the increased influence and power of religious institutions or the underclass. In a place such as Shanghai such phenomena were concentrated and their proliferation accelerated, however; furthermore the editors, writers, and artists of the pictorial always saw the paper as a platform to express their opinions. Viewers, on the other hand, may have derived alternate interpretations from some of the frankly humorous or titillating stories and illustrations. [12]

|

|

| |

“Prostitute Tumbles from Building”

|

|

| |

If Wu Youru was the master of the naval battle, Jin Chanxiang (Jin Gui)—after Wu, the second most prolific Dianshizhai artist—flourished amid the courtesans and the uncanny. [13] His rendering of the accidental tumble of a courtesan and her companion from a Shanghai teahouse balcony uses motion to suggest perspective, thrusting the unfortunate pair towards the viewer. Thus he transforms what in the text is a tale of urban change and decay into a comical scene. [14]

|

|

|

|

“Prostitute Tumbles from Building”

妓女墜樓

1886 geng (Vol. 9, p. 40)

artist Jin Gui (Jin Chanxiang)

Yale 9.041 [dz_v09_041]

Translated caption:

“During the early Tongzhi reign, Lishui Tai started the trend of grandiose teahouses in the northern district Hubei section of Shanghai. The three-floor teahouse faces the river, the spacious building allowing people to enjoy the sunshine in winter and to escape heat in summer. The alley to the west was occupied by brothels, where people could converse with customers at the teahouse’s balustrade. ...

[View caption & English translation]

Translated by Alec Wang

|

|

| |

Tian Zilin also employs the drama of bodies captured in violent motion to excellent effect in depicting the shooting of a Japanese consular official in Germany by his Belgian lover, “Jenny”, upon her discovery that he was already married. Tian’s imagination of the German surroundings of a Meiji official speak more to Shanghai: the European-style buildings are filled with a mixture of Chinese and Western furnishings. The riot of pattern on Jenny’s clothing is a magnificent display of the merging of woodblock technique and the possibilities of the lithograph. But the shooting itself is the tour de force: the detail of the weapon (and the spare on the table), the billow of the discharge, and the flying body of the consul.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Along with science, gender, and the body, religion constituted a flash point in the pages of the Dianshizhai Pictorial and its parent publication Shenbao. Perhaps even more so than those other topics, with religion the conflict was subtle, as the 1880s and 1890s were a period of gradual shifts in concepts and attitudes. Critiques of aspects of the Chinese religious landscape launched from a perspective that might be termed Confucian moralist—suspicion, skepticism, or competitive attitudes towards Buddhist and Daoist clergy, disdain for popular healers, and concern over wastefulness in ritual expenditures—began to merge with the very new concept that religion in general might be condemned wholesale as unscientific and therefore “superstitious.” [15]

Yet Shanghai—along with the Jiangnan region as well as other treaty ports and large cities—was at the same time the center of renewed vigor in religious and philanthropic activity in the wake of the cataclysmic destruction of the Taiping Rebellion and China’s numerous other midcentury domestic and foreign conflicts, as well as natural disasters such as the massive 1876–79 North China Famine. The “merchant literati” writing, illustrating, reading, and viewing the Dianshizhai were enmeshed in all elements of this matrix. Critique of the social dangers of religious excess appears alongside expressions of devotion, as well as an emerging sense of China on the world religious stage. [16]

| |

| |

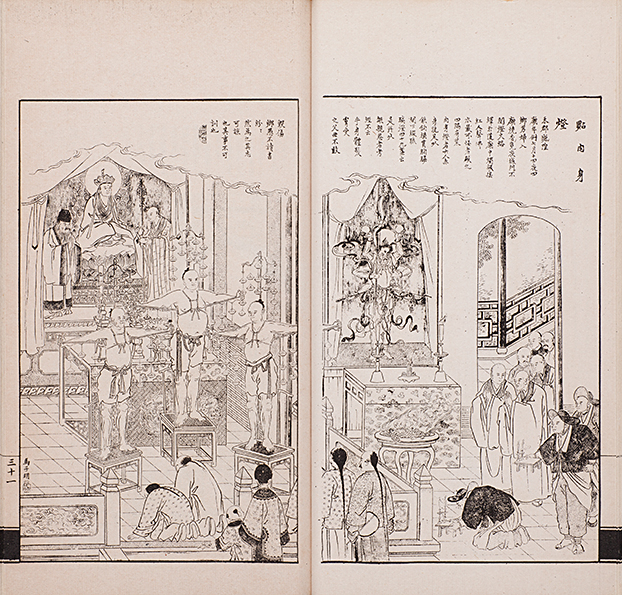

“Lighting Human Flesh Lamps”

|

|

| |

Thus “Lighting Flesh Lamps” voices a longstanding literati complaint about the unseemly spectacle of temple festivals—especially “hot and noisy” and potentially heterodox festivals such as those surrounding Zhongyuan (Yulanpen or Yulanbang), the central point of the seventh lunar month, or the “ghost festival.” Rites for the care and management of wandering ghosts mixed the sexes and classes and involved ritual specialists and temples of a variety of backgrounds—Buddhist, Daoist, local religion, and more. As with a great range of Chinese religious activity, it was not so much that literati eschewed the Ghost Festival completely as they objected to certain aspects of it while wholly participating in others (such as supporting the performance of devotional operas centered around the tale of the filial son Mulian).

Here the objection is to the transformation of bodies into penitential offerings by hanging lights or incense burners from the extremities: the creation of so-called “human flesh lamps.” In Ma Ziming’s illustration the penitents stand inside a City God temple, and in front and in reverence of the bodhisattva Dizang (Kṣitigarbha), who delivers the dead from the punishments of hell. Though the text condescends to the “unread village ignoramuses” who could be forgiven for believing fallacies such as the imperviousness of the flesh of the devoted, as with the case of the head of the Wild Man, the lithograph serves to demonstrate—and thus in a way disseminate—the very practice being condemned. Graphic details such as the pilgrims in the lower right corner, with their mobile altars stocked with candles and offerings, offer rare and intriguing visual records. [17]

|

|

|

|

“Lighting Human Flesh Lamps”

點肉身燈

1886 (Vol. 11, p. 30)

artist Ma Ziming

Yale 11.032 [dz_v11_032]

Translated caption:

“Lighting Human Flesh Lamps.

In the evening of the fourteenth day of the seventh moon, the traditional Ghost Festival, worshippers flock from far and wide to the Temple of the City God in He prefecture to pray and make offerings of incense. The gates of the city, left open throughout the night, accommodate a seemingly endless stream of worshippers. The entire temple is aglow, as countless oil lamps flicker, and the voices of the faithful bubble up like the sound of water. Most extraordinarily, however, six human lamp stands stand in corners of the temple ...

[View caption & English translation]

|

|

| |

“Inviting Courtesans to the Underworld”

|

|

| |

News about religion could also comfortably fit into the category of the weird, allowing for more diversion than anxiety. Best of all was when these themes overlapped with other favorite genres for entertainment, such as in this perfect storm of a story, in which the talented and beautiful courtesans Fengbao and Fengzhu of the Jiangxi brothel Caifeng Tang were summoned to a mysterious location, only to find themselves in a temple graveyard, engaged to perform for a deceased audience. [18]

|

|

| |

This period was precisely the one in which Chinese religion—and religion as a marker of civilization and national culture more generally—was placed on a world stage. In fact, this was the very major source of the growing elite anxiety about the nature of Chinese religious practice. In 1893 representatives of select Chinese “faiths” would be invited to attend the World’s Parliament of Religions that followed upon the Columbian Exposition in Chicago; for people like Peng Guangyu, the “Confucian” representative, the urgency to lay claim to civilizational values and national characteristics was keen, and this mission was shared by Indian Hindus, Japanese and Sri Lankan Buddhists, and other delegates of the colonized and semi-colonized world allowed a place at the table.

| |

| |

“French People Worship Buddha”

|

|

| |

The opportunity to present Chinese religion to the world meant not only a chance to argue for its legitimacy (in the face of competing claims from Christianity in particular), but to extend its viability. In this piece describing the recent spread of Buddhism to France, the author laments the decline of deep understanding of Buddhism in China and concomitant rise of popular ritualism—a common literati refrain. China really had no special claim on Buddhism, which came from the West in any case (India and Tibet). Thus it was refreshing that, reportedly, 30,000 Parisians had contributed towards a statue of the Maitreya Buddha, and many were poised to take Buddhist vows. In Jin Chanxiang’s visual imagination, such European Buddhist worship would naturally take place in a superficially converted church, with the attendance of monks and nuns who would adhere to the clerical garb of local custom: French Catholic.

|

|

| |

“Processing the Deity into the Temple”

|

|

| |

We conclude with a story and an illustration that show that the Dianshizhai also appreciated religion for its place in the city—for the spectacle it offered, for its role in knitting together social networks, and, simply, for the merit and fortune it bestowed upon the city’s inhabitants. In a grand, two-page image that can be compared to the Tianhou procession with the brass band shown in Chapter Two [view], Wu Youru illustrated the full procession dedicating a new Tianhou temple erected at the old site of the Hongkou Railway Station. Along with the musicians, attendants, adults and children in costume, Chinese and foreign policemen, and deities in their palanquins, the image and text point out the presence of representatives of the Cantonese and Fujianese communities in Shanghai. “It really was a most magnificent procession,” the text concludes, “a vast panorama of Great Peace.” [19]

|

|

|

|

“Processing the Deity into the Temple”

迎神入廟

1884 (Vol 2, p.s 4 & 5)

artist Wu Youru

Yale 2.005, 006 [dz_v02_006] [dz_v02_005]

|

|

| |

Translated caption:

“Processing the Deity into the Temple

The new temple of the Queen of Heaven has been built on the site of the previous Hongkou Railway station. On the twenty-fourth day of the fifth month, the statue was carried in procession from the Imperial Quarters and the East gate to the new temple. As it passed through the International Settlement and the French concession, crowds lined the streets, standing still in rapt attention. ...”

(Translation by Peter Perdue, revised from Ye, pp. 199-200)

[View caption & English translation]

|

|

|