| |

SHANGHAI MYTHS

Jeffrey Wasserstrom

Introduction

The urban theorist Michael Sorkin, fascinated by the degree to which Los Angeles had become associated with Hollywood imagery and hyperbolic statements about its rise to fame and infamy, once described the metropolis as having become “virtually unviewable save through the fictive scrim of its mythologizers.” [1] The same is true for Shanghai, another celebrated and notorious Pacific-rim city that by the 1930s had rocketed to a position of global fame and infamy.

Written works have played an important role in Shanghai’s modern mythologizing, which began in the wake of the Opium War (1839–1842) that ended with a diplomatic agreement that made it one of five special “treaty ports” along the China coast in which Britons would have the right to settle and conduct business according to the rules of their homeland rather than those of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). In the case of both Shanghai and Los Angeles, visuals as well as words contributed to the “fictive scrim” in which these great cities became encased. For Los Angeles, brochures, postcards, and films of the early 1900s showing palm-tree-lined boulevards did much of the mythologizing work (with other media such as television supplementing them later on). For Shanghai, which began its surge to mythic status a bit earlier, line drawings such as those found in the Illustrated London News and Dianshizhai were particularly significant at the start of the process.

The period of the Dianshizhai’s publication was a crucial one in the formation and circulation of two especially significant partially true and partially misleading stories about Shanghai. For simplicity’s sake, these can be called the “Fishing Village Legend” and the “China-meets-the-West City Tale.” These two stories deserve to be treated as two of Shanghai’s most important and enduring “city myths”—a term borrowed here from another insightful analyst of Los Angeles, Mike Davis. In his classic work on Southern California, in which he limns the powerful “sunshine” and “noir” visions of Los Angeles, Davis employs “city myths” to refer to deeply embedded narratives that come to define an urban center and are often used for strategic purposes, from legitimating a set of political relationship to encouraging outsiders to move to or invest in the place. [2]

Visual materials unquestionably helped to spread the partly misleading notions associated with the two Shanghai city myths in question. At the same time, however, such graphics can also be used to pierce through the “fictive scrim” of these deeply entrenched notions, revealing things that the “Fishing Village Legend” and “China-Meets-the-West City Tale” conceal or force into the shadows. Sometimes, this fiction-busting function can only be achieved by moving from one image to another, with one that reinforces the myth giving way to one that exposes not so much its falseness but its limitations. In other cases, though, all it takes is looking very closely at an image that seems at first to confirm a city myth.

What exactly is the “Fishing Village Legend,” and how is it misleading? It is an approach to narrating Shanghai’s past that asserts or takes for granted that Shanghai lacked all trappings of an urban center before the Qing leaders were pressured into signing the Treaty of Nanjing in 1843. Thereafter, the legend goes, Shanghai very rapidly evolved, through an almost magical process, into one of the world’s great cities. In some versions of the story, the growth of the city is described, in fairy tale-like terms, as a site awakening to a great destiny. Phrases such as Shanghai being in pre-Opium War times merely a “wilderness of marshes” or “city of reeds” rather than buildings are used. [3]

The problem with this legend is simple. While Shanghai changed dramatically and grew exponentially after the terms of the Treaty of Nanjing were implemented, it was much more than a “fishing village” prior to that point. It was not the most important or even second most important city of the region. Those distinctions belonged to Suzhou and Hangzhou, and Shanghai was sometimes called “Little Su” or “Little Hang” to flag its lowlier status. And the changes it underwent after the Opium War were extraordinary—leading eventually to Suzhou and Hangzhou being seen as satellites to Shanghai. Still, Shanghai already had temples, stores, a city wall, and all the trappings of a Chinese urban center before the Opium War.

One kind of written text that points to the problem with the “fishing village” myth are descriptions of Shanghai as a bustling port, filled with ships carrying goods from China’s hinterland to Southeast Asia, that appear in works of the pre-Opium War era by early Western visitors. A European account of a visit early in the 1830s described it as the “famed emporium” of Shanghai where “a vast number of junks of every variety” could be found. Later in the decade, the Chinese Repository referred to it as a “large commercial place.”

|

|

|

| |

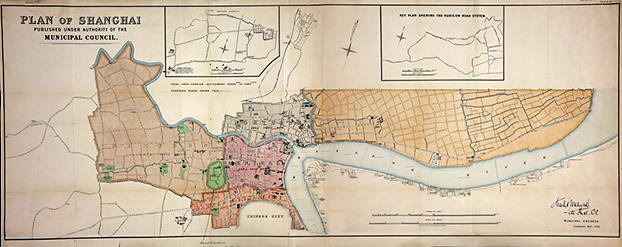

Plan of Shanghai, 1904

Map ID-76, No-1

Source: Virtual Shanghai Project [view]

[dz500]

|

|

| |

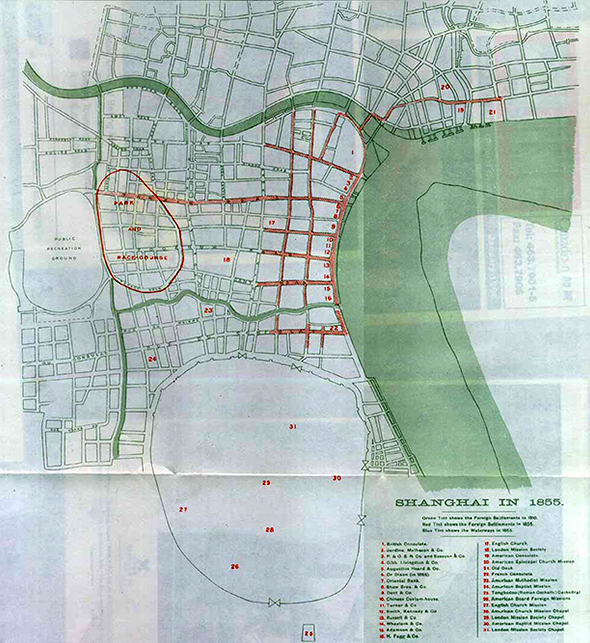

This map was made by the Shanghai Municipal Council, which ran the International Settlement, so it makes sense that that district is shown in more detail; but the French Concession, a separate entity, gets detailed attention while Chinese districts do not. This 1855 map, meanwhile, shows the old walled city, but the only points of interest in it are buildings built by missionaries after the Opium War, suggesting that the area lacked structures of significance before then.

|

|

Map of Shanghai

1855

Source: Earnshaw

[view]

[dz501] |

|

| |

The limitations of such cartographic imperialism are exposed dramatically by other maps from the early and late 1800s that show the foreign-run and Chinese-run parts of the city in a more holistic fashion, suggesting a metropolis that had grown dramatically but by no means had gone from nothing to something nearly overnight.

|

|

| |

Map of Shanghai, 1800-1820

Original title: 上海縣城圖

Source: Virtual Shanghai Project [view]

[dz502] |

|

| |

The City Where China-Meets-the-West

The second misleading story revolves around the idea that Shanghai in particular, and treaty ports more generally, became in the 1840s special sorts of Orient-meets-Occident locales. As this myth would have it, they became places defined by juxtapositions of “Chinese” individuals, objects, customs, and lifestyles, on the one hand, and “Western” ones, on the other. Where Shanghai is concerned, there is more substance to this notion than to the “fishing village” legend.

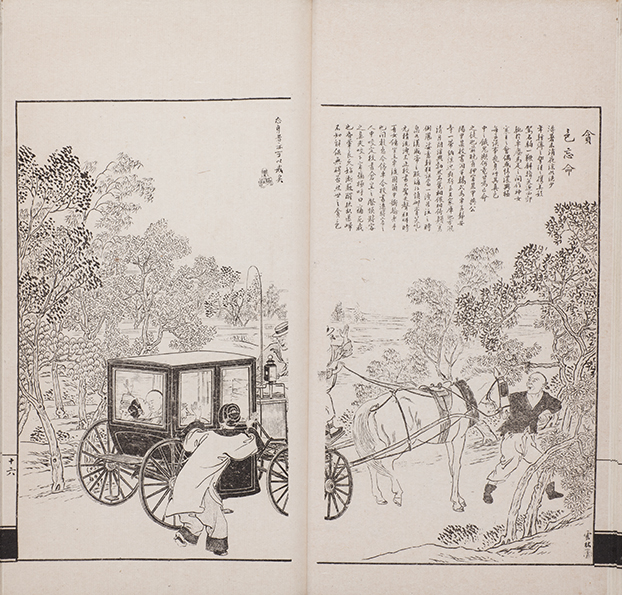

By the time Dianshizhai was launched, and for many decades after, Shanghai was divided into Western-run and Chinese-run districts, something that was also true of other treaty ports such as Xiamen and Tianjin. All of these hybrid locales were important in linking China to the West. The period saw these treaty ports go from having completely Chinese populations to having populations that included Westerners. They also became places where vehicles from the West, such as horse-drawn coaches of the kind shown here (one of many Dianshizhai images to feature such conveyances) became commonplace on local streets, some of which were paved in the style of European and American cities.

|

|

|

|

“Giving up Life for Lust”

貪色忘命 “Giving up Life for Lust”

貪色忘命

1896 heng (vol. 38, p. 16)

[View caption & English translation]

Yale 7.017 [dz_v07_017]

The close-up detail

reveals a couple

kissing in the back seat.

|

|

| |

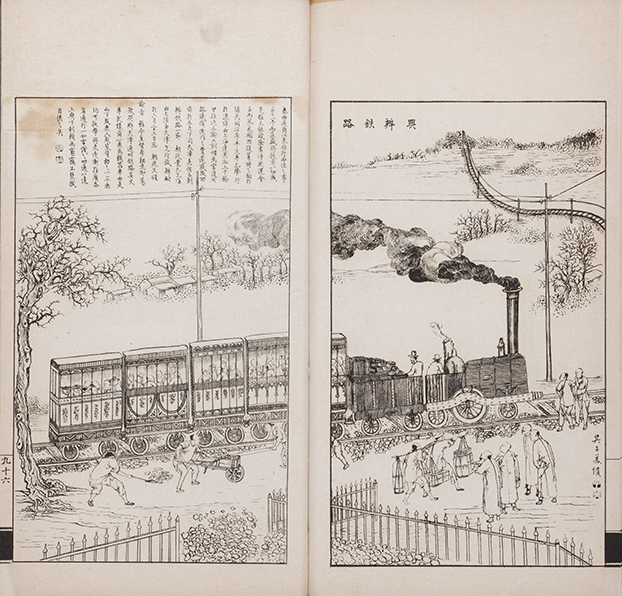

Shanghai usually outpaced other treaty ports when it came to importing Western modes of transportation, though in the case of trains, as the illustration below from the Dianshizhai makes clear, it had to share early-adopter honors with the most important treaty port in North China.

|

|

|

|

“Launching the Railway” “Launching the Railway”

1884 jia (Vol. 2, p. 47 )

artist Wu Youru

Yale 1.029 [dz_v02_048]

“Since the commencement of a trading relationship with the West, it has grown increasingly popular in recent years to emulate Western ways. Even though not all stereotypes and prejudices have been discarded, the era of meticulously observing rigid conventions has gone, the tide of opinion has changed, and a new climate has set in. In the last year of the Tongzhi Reign (1874), trains appeared for the first time in Shanghai ... ”

[View full caption & English translation]

|

|

| |

Last but not least, by the 1880s Shanghai’s famous waterfront area known as the Bund confirmed that there was some basis to the China-plus-elements-of-the-West vision of the city. When Dianshizhai began publishing, the Bund, which ran along the eastern edge of both the International Settlement and the French Concession, had a series of buildings that frequently appeared in paintings and photographs. Most of them had a distinctively Western look, having been built it what was known as the “colonial” style, but one that stood roughly midway up the Bund, called the “Custom House,” had a distinctively Chinese look, with a sloping tiled roof.

|

|

| |

Imperial Chinese Maritime Customs (first building), 1857-1891

Source: Virtual Shanghai Project [view]

[dz503] |

|

| |

At the Bund’s northern end, moreover, there was a park, complete with a gazebo, which looked as though it could have been transplanted directly from London. Images of this park, known as the Public Garden, sometimes showed it with junks sailing nearby, one more visual way of marking that Shanghai had a look that evoked Europe yet was clearly in China.

|

|

| |

Postcard of the Public Garden, 1908

Source: Virtual Shanghai Project [view]

[dz504] |

|

| |

Just to the west of the Bund was a racecourse that looked much like the ones found in Britain itself and in various British colonies, including Hong Kong. Not far from that were some of Shanghai’s French churches, which resembled those found in France and cities in other parts of the world that were part of its empire, such as Saigon. And in both the International Settlement and the French Concession, there were many buildings with clocks that looked like those found in the United States and in European cities. The most famous of these was built on the same spot as the Custom House, which was torn down in the early 1890s to make room for a Big Ben-like structure.

|

|

| |

Chinese Maritime Customs House (second building), 1893

Source: Virtual Shanghai Project [view]

[dz505] |

|

| |

The new building also served as headquarters for the customs service. It opened to much fanfare in 1893—the year foreign residents held a “Jubilee” to mark the city’s fiftieth “birthday,” or more accurately the anniversary of the arrival of the first Western settlers. From that point on, the Bund contained only Western-style buildings. (When the Custom House was torn down again in the 1920s, it was replaced with another clock-towered structure that remains in place to this day.)

|

|

| |

View of the Bund, 1929

Source: Virtual Shanghai Project [view]

[dz506] |

|

| |

Pictures of the Bund commonly included the waterfront, with junks that made clear to viewers that it was not actually in Europe. This did not stop one British visitor, a young Margot Fonteyn, the later-famous ballerina, from remarking upon arrival after a stay in North America that Shanghai looked more like London than any city in the United States had. [4] To move between these Western-style landmarks, one passed shops and homes that were built in traditional Chinese styles, as well as structures that mixed local and imported architectural motifs and forms of construction.

In light of all of this, it is understandable that one of Shanghai’s main nicknames became “Paris of the East,” a sobriquet also used in the late 1800s and after for a host of other cities, from Bucharest to Beirut, that were outside of Western Europe yet seen as influenced by that part of the world. It was also referred to as the “New York of the West”—a much less common term, but used, for example, in All About Shanghai and Environs, one of the most widely read foreign guidebooks of the time.

What, then, makes the China-meets-the-West vision of Shanghai a city myth rather than a straightforward description of reality? The answer is simple. While the city was certainly marked by cosmopolitanism and a mingling of influences and people, this involved more than just a jumbling together of “Chinese” and “Western” elements. Shanghai was an East-meets-East as well as China-meets-West locale.

The Dianshizhai is an ideal source to use to explore this issue. At first pass, it seems to give substance to the China-meets-the-West idea, but on closer inspection can be used to demonstrate the importance of making room for an East-meets-East vision of Shanghai.

First, consider its China-meets-the-West dimensions. Like the Shenbao newspaper to which it was linked, its publisher was a Briton but most of its employees were Chinese. Its drawings were clearly influenced by British and French illustrated magazines, yet Chinese aesthetic and artistic traditions also shaped the look of its images—and all of its textual glosses were written in characters. Some drawings showed Western events, some showed purely Chinese ones, and some portrayed mixed groups of Chinese and Western individuals. Many graphics depicted purely Chinese groups wearing apparel or surrounded by objects—from macadamized streets with street lamps to buildings with clock towers to horse-drawn carriages—that brought the West to mind. [5]

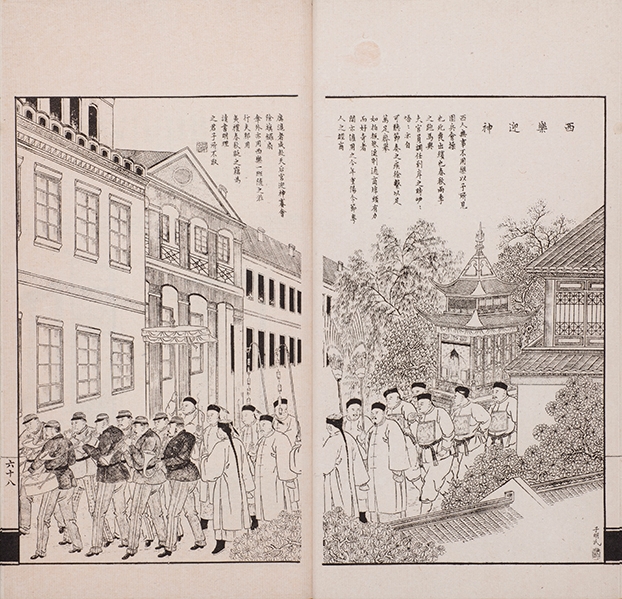

Several Dianshizhai images could serve as poster children for the “Shanghai as a China-Meets-the-West locale” idea. One that is often reproduced depicts a parade sponsored by a local guild titled “Western Music in a Religious Ceremony.”

|

|

|

| |

It shows a mix of Chinese and Western musicians walking together while playing instruments associated with both China and the West. The accompanying gloss, which adopts a critical tone, describes the scene as an example of a Chinese group that has gone too far in being influenced by foreign fashions, in this case by hiring Westerners to perform in one of the sponsoring guild’s rituals. Accompanying text reads in translation:Westerners use music to accompany everything. According to what I have seen, this includes military parades, funerals, the horse races held in the spring and autumn, and officials arriving at the quay to take up a new position. Yi-yi-ya-ya—it is quite pleasant to the ear. The tempo and the rhythm are like the movement of 10,000 feet, like beating time with clappers. Sometimes people with the means and curiosity in this commercial port hire such performers. This year, at Double Nine Festival, Cantonese merchants resident in Shanghai participated in the procession to the Temple of the Queen of Heaven. Apart from the usual banners, gongs, fans, and umbrellas, they hired a Western band to accompany the procession. Anyone with any education would not have thought of anything so vulgar.

[Translation by Ye Xiaoqing in her The Dianshizhai Pictorial, p. 132.]

Nevertheless, a closer look at the publication reveals a good deal of evidence of Shanghai’s “East-meets-East” dimensions. Some of the images that seem at first glance to be purely China-meets-the-West pictures actually reflect an Asian but non-Chinese presence in their portrayals of individuals and objects. This is true even in the built environment and settings that are typically described as emblematic of the city’s China-meets-the-West character.

A case in point is the richly detailed image of the local racecourse that also appears at the start of this unit. The viewer sees Western jockeys on racehorses, a crowd made up of mostly Chinese but some Western spectators, a mix of horse-drawn carriages and palanquins, and the racecourse surrounded by buildings that look Western in style (at the top of the image, below), or Chinese in style (at the bottom). All of this fits a China-meets-the-West reading. Yet, a third key form of transportation is shown at the bottom, left: rickshaws. These were a Japanese import. In Western representations of Shanghai, they could be used to stand for its non-Western aspects but they were no less an import than the horse-drawn coaches.

|

|

| |

The racecourse image can thus be seen as one that shows Shanghai as primarily defined by China-meets-the-West elements, with one East-meets-East element slipped in. The same can be said of another image in which we see markers of the Western presence in Shanghai (the ship’s mast, the architecture, the sunglasses), but also a rickshaw.

|

|

| |

Elsewhere, though, a rickshaw may be the sole indication of foreign influence, as shown in the image below. A Chinese viewer living in a setting other than a treaty port might well latch onto the rickshaws as key indicators that this was not a street scene in just any random urban center of the Qing Empire, but one shaped by international current.

|

|

| |

Rickshaws are not the only East-meets-East element of Shanghai that makes regular appearances in images of the treaty port. Equally noteworthy—and almost equally iconic a part of the Shanghai landscape—is the turbaned Sikh policeman. The police force of the International Settlement was a robustly cosmopolitan one, with Chinese constables, British supervisors, and members of different nationalities. Included in its ranks were Sikhs, who were sometimes shown keeping Chinese from entering areas set aside for Western use, patrolling streets that had Western-style buildings, keeping order in settings that symbolized European or North American presence (such as the Public Garden), and so on. [6]

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Both of the city myths explored here—the “Fishing Village to Great Metropolis” and “Place Where China-Meets-the-West”—took hold late in the 1800s and have persisted to the present. They have gained added force in recent years, as Shanghai has once again undergone dramatic expansion and transformation. Still, as visual evidence underscores, both city myths distort as well as reveal important things about Shanghai in the era of the Dianshizhai. And it is worth keeping in mind that Shanghai’s reglobalization in recent decades has been, like its first globalization back then, more than just a tale of “China-Meeting-the-West”. What was until very recently the tallest building in Pudong, the newest locale of Shanghai urban expansion, was financed largely by Japanese money. And while there are plenty of places to drink Western-style coffee in Shanghai, there are even more places that feature Karaoke, just one of the many East-Meets-East imports that are shaping the 21st century metropolis. [8]

|

|

| |

|

|

|