| |

PROGRESS & PROFITS

“Auto-Truck of Civilization and Trade”: the Asia Market

Civilization and trade went hand in hand in turn-of-the-century imperialism. Progress was promoted as an unassailable value that would bring the world’s barbarians into modern times for their own good and the good of global commerce. As the U.S. moved into the Pacific, “China’s millions” represented an enticing new market, but the eruption of the anti-Christian, anti-foreign Boxer movement threatened the civilizing mission there.

In a striking Judge graphic, an “Auto-Truck of Civilization and Trade” lights a pathway through the darkness, leading with a gun and the message: “Force if Necessary.” Overladen with manufactured goods and modern technology, the vehicle is driven by a resolute Uncle Sam. Blocking its uphill path, the Chinese dragon crawls downhill bearing a “Boxer” waving a bloody sword and banner reading “400 Million Barbarians.” The image puts progress and primitivism on a collision course at the edge of a cliff. Fears that China would descend into chaos and xenophobia justified intervention to safeguard the spread of modernity, civilization, and trade. The image argues that a crisis point has been reached and the caption states, “Some One Must Back Up.”

|

|

|

|

“Some One Must Back Up.” (detail)

Judge, December 8, 1900

Artist: Victor Gillam

Source: Widener Library, Harvard University

[cb27-004_1900_Judge_BackUp_000016]

|

|

|

text on left: text on left:

“Auto-Truck of Civilization and Trade”

“Progress”

“Force if Necessary”

“Cotton” “Dry Goods” “Education”

|

text on right: text on right:

“Boxer”

“400 Million Barbarians”

“China” |

|

|

Civilization and barbarism meet as the headlight of Uncle Sam’s gun-mounted “Auto-Truck of Civilization and Trade” shines the light of “Progress” on “China.” Published during the Boxer uprisings against Westerners and Christians, the cartoon portrays China as a frenzied dragon under the control of a “Boxer” gripping a bloody sword and banner reading “400 Million Barbarians.” In the balance of power between technological “progress” and primitive “barbarians,” the cartoon makes clear who “must back up.”

|

|

| |

The link between U.S. conquest of the Philippines and the lure of the China market was widely acknowledged at the time, and no one rendered this more vividly, concisely, and admiringly than the cartoonist Emil Flohri. One cannot imagine a blunter caption than the one that accompanied his 1900 cartoon for Judge: “And, after all, the Philippines Are Only the Stepping-Stone to China.” In Flohri’s image, Uncle Sam—heavily laden with steel, railroads, bridges, farm equipment, and the like—gives a cursory nod to the spread of civilization by grasping a book titled "Education" and "Religion.” The confident giant is greeted with open arms by a diminutive yellow-clad Chinese mandarin.

Anticipated U.S. exports appear on signs that advertise the rich market awaiting American manufacturers. Each sign is topped by the word “Wanted” and the goods listed include trolley lines, electric lights, water-works, sewers, paving, asphalt roads, watches, clocks, wagons, carriages, trucks, 100,000 bridges, 500,000 engines, 2 million cars, 4 million rails, 100,000 RR stations, cotton goods, telegraph, telephone, stoves, lamps, petroleum, medicines, chemicals, disinfectants, 50 million reaping machines, 100 million plows, and 50 million sewing machines.

|

|

|

|

“And, After All, the Philippines are Only the Stepping-Stone to China.”

Judge, ca. 1900

Artist: Emil Flohri

Source: Wikimedia [view]

[cb28-038_1900_Mar21_Judge_Philippines_wm]

The Philippines are diminished as “Only the Stepping-Stone” that enables the U.S. to reach the eagerly anticipated China market. Along with his burden of steel, trains, sewing machines, and other industrial goods, Uncle Sam carries a book titled “Education, Religion” in a nod to the rhetoric of moral uplift that accompanied the commercial goals of the civilizing mission. He is greeted with open arms by a mandarin and “Wanted...” signs articulating prodigious opportunities for business.

|

|

| |

Commercial interests not only drove U.S. policy in Asia, but also shaped public opinion about it. The artist George Benjamin Luts offered an exceptionally scathing rendering of the linkage of conquest, commerce, and censorship in an 1899 cartoon titled “The Way We Get the War News: The Manila Correspondent and the McKinley Censorship.” Published in a short-lived radical periodical, The Verdict, the cartoon shows a war correspondent in chains, writing his story under the direction of military brass. Business and government colluded with the military in silencing press coverage of the poor conditions suffered by American soldiers, including scandals around tainted supplies, and the grim realities of the Philippine-American War itself—censorship that foreshadowed the broader excising of the unpleasant war from national memory. Robert L. Gambone in his 2009 book, Life on the Press: The Popular Art and Illustrations of George Benjamin Luks, describes the cartoon as follows:

...The Way We Get Our War News (The Verdict, August 21, 1899, front cover) excoriates military press censorship, a supremely ironic development given the appeals to freedom used to justify the war. Within a barred room, its walls painted blood-red, a cohort of five army officers headed by a sword-wielding Major General Elwell Stephen Otis (1838-1909), military governor of the Philippines, forces a manacled war correspondent to write only approved dispatches. A mound of scribbled papers from an overflowing wastebasket testifies to the coercion exerted upon him to induce cooperation. [p. 199]

|

|

"The Way We Get the War News.

The Manila Correspondent and the McKinley Censorship.”

Artist: George Benjamin Luts

The Verdict, August 21, 1899

Source: Houghton Library, Harvard University

[cb29-151_1899_Aug21_Verdict_Houghton]

A chained “War Correspondent” is forced to rewrite his reports under the direction of Major General Elwell Otis during the Philippine-American War. As the military governor until May 1900, Otis inflated Filipino atrocities and prevented journalists, Red Cross officials, and soldiers from reporting American atrocities, though ghastly accounts slipped through. The cartoonist targets capitalists as the true power behind the policies and practices in the Pacific, with a portrait of businessman Marcus Hanna—a dollar sign elongating his ear—that dwarfs a portrait of President William McKinley. |

|

| |

In the background, the artist placed a large portrait of a large man, Marcus Hanna, next to a miniature of President William McKinley to show their relative influence on policy. Hanna was a wealthy businessman with investments in coal and iron who financed McKinley’s 1896 election campaign with record-breaking fundraising that led to the defeat of opponent William Jennings Bryan. (In the 1900 elections, Bryan ran on an anti-imperialist platform and was again defeated by McKinley.) Gambone described the portraits as, “a testament to the weakness of McKinley, the overarching power of Hanna, and the Trust interests that supported expansion of American business into the Pacific.”

The foothold in the Philippines brought China within reach. As the golden goose, China’s perceived mass market was to be protected for free trade against takeover by increasingly assertive foreign powers. Boxer attacks on Western infrastructure and the siege of foreign diplomats in Beijing gave the international powers a pretext for entering China with military force. Though “carving the Chinese melon” was a popular metaphor, none of the invaders seriously considered partitioning the large country under foreign rule. (The exception would be Manchuria, alternating between Russian and Japanese control in the coming years.) But rivalries for commercial privileges never abated even when an eight-nation Allied military force was forged between the world powers in the summer of 1900.

In the West, China was often characterized as befuddled and archaic under the rule of an inscrutable crone, the Empress Dowager. In Puck’s October 19, 1898 cover, “Civilization” holds “China” by his queue, labeled “Worn Out Traditions,” ready to cut it off with the shears of “19th Century Progress.” The helpless mandarin tries to run away. It was feared that the mystical rituals and xenophobic violence of the Yi He Tuan (Boxer) secret society would overwhelm China’s ineffectual rulers, cast the country into chaos, and hinder the trade and profits anticipated by the great powers.

|

|

| |

| |

| |

“The Pigtail Has Got to Go”

Puck, October 19, 1898

Artist: Louis Dalrymple

Source: Beinecke Rare Books & Manuscripts, Yale University

[cb30-021_puck_1898_Oct19_cover_1290]

A white, feminine personification of “Civilization” (written on her cloak) radiates light over the aged figure of “China” (written on his hem) running away and shielding himself with a parasol. Civilization and progress are inseparable, a train and telegraph drawn in her robes. China’s “Worn Out Traditions”—represented by the queue hairstyle required during the Qing dynasty—are about to be cut with the shears of “19th Century Progress.”

|

|

| |

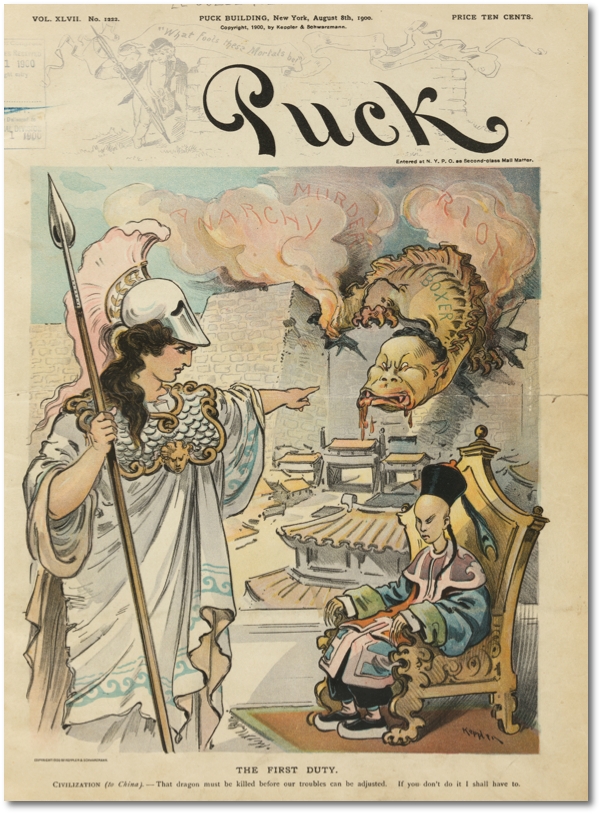

Nearly two years later, in the midst of the Boxer Uprising, Puck was still resorting to the same sort of stereotyped juxtaposition. On the magazine’s cover for August 8, 1900, the familiar feminized and godlike personification of the West points at a slavering dragon, labeled “Boxer,” crawling over the wall of the capital city. Now clad in armor and carrying a spear, she threatens to intervene to stop the anti-foreign, anti-Christian acts of “anarchy, “murder,” and “riot” that have spread to Beijing. China’s hapless young Manchu emperor, traditionally and exotically robed, sits passively in the foreground. The caption, titled “The First Duty,” carries this subtitle: “Civilization (to China)—That dragon must be killed before our troubles can be adjusted. If you don’t do it I shall have to.”

|

|

|

| |

“The First Duty. Civilization (to China). — That dragon must be killed before our troubles can be adjusted. If you don’t do it I shall have to.”

Puck, August 8, 1900

Artist: Udo Keppler

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[cb31-105_1900_PUCK_Aug8_1stDuty_25445u_loc]

“Civilization” warns China’s passive emperor to stop the “Anarchy,” “Murder,” and “Riot” spread by Boxer insurgents—visualized as a dragon crawling over the city wall—attacking missionaries, Chinese Christians, and Westerners. When this cartoon was published, the foreign Legation Quarter in Beijing was besieged by Boxers and Qing troops. Lasting from June 20 to August 14, 1900, the siege was the catalyst for a rescue mission by the Allied forces of eight major world powers.

|

|

| |

“School Begins”: Unfit for Self-Rule

Invading foreign lands was a relatively new experience for the U.S. Given the rhetoric of civilizing uplift used to justify expansion, training was expected as part of the incorporation of new territories into the U.S. Uneasiness over the idea of using force to govern a country was overcome by tracing the issue of consent back through recent history. An elaborate Puck graphic from early in 1899 called “School Begins” incorporates all the players in a classroom scene to illustrate the legitimacy of governing without consent. In the caption, Uncle Sam lectures: “(to his new class in Civilization): Now, children, you've got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!”

The blackboard contains the lessons learned from Great Britain on how to govern a colony and bring them into the civilized world, stating, “... By not waiting for their consent she has greatly advanced the world's civilization. — The U.S. must govern its new territories with or without their consent until they can govern themselves.” Veneration of Britain’s treatment of colonies as a positive model attests to the significant shift in the American world view given U.S. origins in relation to the mother country. Even the Civil War is referenced, in a wall plaque: “The Confederate States refused their consent to be governed; but the Union was preserved without their consent.” Refuting the right of indigenous rule was based on demonstrating a population’s lack of preparation for self-governance.

The image exhibits a racist hierarchy that places a dominant white American male in the center, and on the fringes, an African-American washing the windows and Native-American reading a primer upside down. China, shown gripping a schoolbook in the doorway, has not yet entered the scene. Girls are part of the obedient older class studying books labeled “California, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.” The only non-white student in the older group holds the book titled “Alaska” and is neatly coifed in contrast to the unruly new class made up of the “Philippines, Hawaii, Porto Rico, and Cuba.” All are depicted as dark-skinned and childish.

|

|

|

|

“School Begins”

Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization):

Now, children, you've got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!”

Puck, January 25, 1899

Artist: Louis Dalrymple

Source: Beinecke Rare Books & Manuscripts, Yale University

[cb36-022_puck_1899_18980125_yale]

|

|

|

Details from “School Begins”

Louis Dalrymple’s exceptionally detailed 1899 Puck graphic includes racist and denigrating depictions within a schoolhouse metaphor to demonstrate the right to govern newly acquired territories without their consent. The argument follows England’s example, as spelled out on the blackboard, that “By not waiting for their consent, she has greatly advanced the world’s civilization.”

|

|

|

|

(Left background) An African-American washes windows.

(Left background) An African-American washes windows.

(Left foreground) The book on the desk reads: “U.S. First Lessons in Self Government.”

The paper on desk reads: “The New Class. Philippines, Hawaii, Cuba, Porto Rico.”

|

(Center) A Native American reads a book upside down and a prospective Chinese pupil stands in the doorway. (Center) A Native American reads a book upside down and a prospective Chinese pupil stands in the doorway.

The wall sign overhead reads: “The Confederate States refused their consent to be governed; but the Union was preserved without their consent.” |

|

|

(Right) Class holds schoolbooks labeled “Alaska, Texas, Arizona, California, New Mexico."

Blackboard text: “The consent of the governed is a good thing in theory, but very rare in fact. England has governed her colonies whether they consented or not. By not waiting for their consent she has greatly advanced the world's civilization. — The U.S. must govern its new territories with or without their consent until they can govern themselves.”

|

|

| |

Harper’s Weekly later echoed the classroom scene with a cover captioned “Uncle Sam’s New Class in the Art of Self-Government.” The class is disrupted by revolutionaries from the new U.S. territories of the Philippines and Cuba, whose vicious fight brands them as barbarously unfit for self-rule. Model students Hawaii and “Porto” Rico appear as docile girls learning their lessons. The backdrop to the scene, a large “Map of the United States and Neighboring Countries,” attests to the new position the U.S. has taken in the world, with its overseas territories marked by U.S. flags.

|

|

“Uncle Sam’s New Class in the Art of

Self-Government”

Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, August 27, 1898

Artist: W. A. Rogers

Source: The Ohio State University Cartoon Research Library [view]

[cb37-142_1898_Aug27_Harpers_d_2077_osu]

Uncle Sam breaks up a fight between students identified as “Cuban Ex-Patriot” and “Guerilla” in his “New Class in the Art of Self-Government.” The famous white-haired general, Máximo Gómez, a master of insurgency tactics in the Cuban Independence War (1895–1898) reads a book with his name on it. The president of the First Philippine Republic, Emilio Aguinaldo, is portrayed as a barefoot savage, wild hair escaping from a dunce cap. “Hawaii” and “Porto Rico” are model female students. The large “Map of the United States and Neighboring Countries” is dotted with U.S. flags marking newly-acquired territories. |

|

| |

In its final issue for 1899—a time when the U.S. suppression of Filipino resistance was at its peak—Puck turned to a feel-good holiday graphic to reaffirm this theme of the bounty promised to newly invaded countries and peoples.

|

|

|

| |

“Our Christmas Tree”

Puck, December 27, 1899

Artist: Udo Keppler

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[cb10-101_puck_1899_May3_Peace_28594u]

Columbia and Uncle Sam pluck gifts from “Our Christmas Tree,” including law and order, technology, and education, for overseas territories “Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Philippines,” condescendingly drawn as grateful children.

|

|

| |

The laudatory rhetoric and imagery of a “white man’s burden” and “civilizing mission” received a sharp rejoinder in a cartoon published by Life in April, 1901 under the title “March of the Strenuous Civilization.” In this sardonic rendering of the realities of imperialist expansion, a missionary leads the charge holding a “Missionary Ledger.” Immediately behind him march a sword-brandishing sailor carrying “loot” and a rifle-bearing soldier carrying “booty.” “Science” comes next, clutching “lyddite,” a high explosive first used by the British in the Boer War. “Literature” follows, holding the text of Kipling’s poem, “The White Man’s Burden.” Music plays an organ labeled “Two Step Symphony—‘Dollar Mark Forever.’” Behind Music comes “Sculpture,” holding up a monument to a war hero. “Painting” carried a portfolio inscribed “‘Light. Death to all Schools but Ours.” The last marcher holds up “Drummer’s Samples,” referring to the traveling salesmen of business and commerce.

Skulls dot the landscape ahead in Life’s grim rendering. Vultures hover above the procession, and the artifacts of past civilization are trampled underfoot at the rear.

|

|

|

|

“The March of the Strenuous Civilization.”

Life, April 11, 1901

Artist: C. S. Taylor

Source: Widener Library, Harvard University

[cb96-320_1901_life1901v1_014]

Life’s satire of the “white man’s burden” mystique offers a procession of the supporters of the new imperialism beginning with missionaries and ending with the traveling salesman.

|

|

| |

Even the language of Life’s caption is subversive, for it picks up a famous pro-imperialist speech by Theodore Roosevelt titled “The Strenuous Life.” Delivered on April 10, 1899, two years before Roosevelt became president, the most famous lines of the speech were these:I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife; to preach that highest form of success which comes, not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger...

...So, if we do our duty aright in the Philippines, we will add to that national renown which is the highest and finest part of national life, will greatly benefit the people of the Philippine Islands, and, above all, we will play our part well in the great work of uplifting mankind.

|

|

|